We had made initial inquiries about the menu and found the bill of fare appealing enough.

The coffee shop has become a favorite of ours—not only does it face the channel and afford us an uninterrupted view of ships coming in and leaving, and occasionally of migratory birds on their way to a nearby island to wait out the cold months of the north, being out of the way, it offers its customers hours of undisturbed peace. Which suits the wife and me, since we both crave solitude.

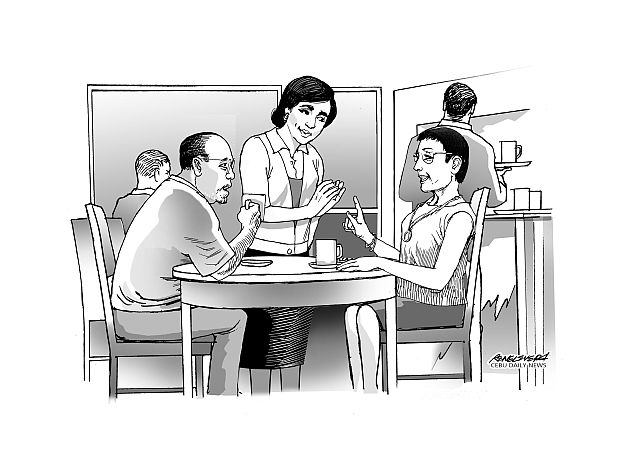

At our last visit, the wife asked about the arrangements—the exact menu items, the arrangement of chairs, the dessert, whether there would be a table for the gifts—matters that, by nature sloppy, I would not have given a thought to. Since the food attendant could not answer all her questions, she sought the help of the manager.

We expected to meet an elderly man or woman, wide of girth and tending towards obesity, the happy fate of a person holding a high position. But the one who approached us, who introduced herself as the manager, had not yet reached thirty, and appeared younger than her crew. She dealt with us with a courtesy that, rather than detract from her decisiveness, made it seem like a favor given. Especially when it came to computing the cost, she did not hesitate to enter into a give-and-take. She showed us that concessions were her department, which made me remark, “Clearly, they would not have made you manager without giving you discretion.”

Of course, I know that such a discretion could lead to abuse. As a judge, I had tried cases in which the manager acted against the interest of her superiors, the owners of the business. And the Gospel of Luke has an example of such a manager in the Parable of the Unjust Steward.

Jesus told his disciples about a rich man who had a steward who was reported to him for squandering his property. After he was summoned and required to give an accounting, the steward told himself, “What shall I do, now that my master is taking the position of steward away from me? I am not strong enough to dig and I am ashamed to beg. I know what I shall do so that, when I am removed from the stewardship, they may welcome me into their homes.” He called in his master’s debtors one by one and ingratiated himself to them by forgiving part of their debts. This act, no matter how fraudulent, impressed the master, who commended the steward for being street-smart.

Jesus noted that “the children of this world are more prudent in dealing with their own generation than are the children of light.” And, ironically, he said, “I tell you, make friends for yourselves with dishonest wealth, so that when it fails, you will be welcomed into eternal dwellings.”

Jesus described worldly wealth as dishonest. I recall what Balzac said, behind every great fortune is a great crime. At any rate, in dealing with wealth, whether dishonest or not, whether one’s own or belonging to another, one should act honorably, as a good steward or manager, who can be counted on in matters big and small.

And if one should come by dishonest wealth, one should use it for good, St. Augustine advises. And if in acquiring the wealth one has become evil, one should not remain evil oneself.

In the Parable of the Unjust Steward, Jesus declared, “No servant can serve two masters. He will either hate one and love the other, or be devoted to one and despise the other. You cannot serve God and mammon.”

St. Augustine defines mammon as “all the riches of the world, from whatever source they come.” He considers them false riches, wealth that is “full of poverty.” For, instead of security, this wealth makes us afraid—of the robber, and even of our servant, who might steal and, more so, kill us and take the money away. In this, his advice is to lose these riches by giving them away—“Lose, that thou be not lost: give that thou mayest gain: sow, that thou mayest reap.”

Which, I suspect, without casting aspersions on the provenance of her employer’s business, the young, kind manager of the coffee shop must have considered, when she gave us a discount.