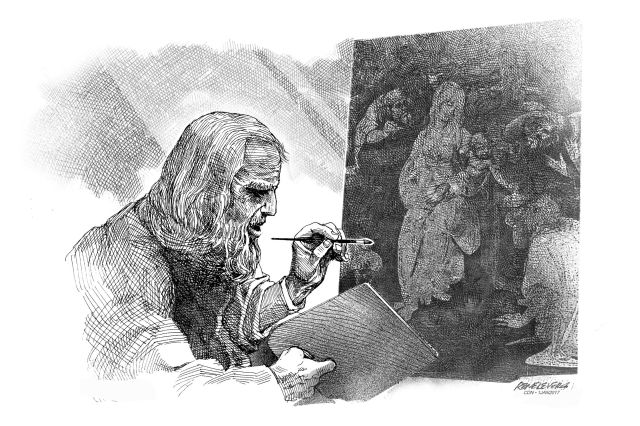

In March 1481, the Augustinian monks of San Donato a Scopelo in Florence commissioned Leonardo da Vinci, then 29 years old, to make a painting for their altar. Leonardo began working on the Adoration of the Magi, but abandoned it when he left for Milan the next year. The unfinished painting, of a honey-yellow color, now hangs in the Uffizi Gallery in Florence.

The Virgin Mary and the Child Jesus occupy the foreground. They form a triangle with the three Magi, who kneel on the ground. People surround them in a semi-circle, and on the far right Leonardo has perhaps his self-portrait. In the background on the left stands a dilapidated pagan building, on which workmen seem to make repairs, and on the right horsemen furiously do battle.

I do not find the painting a traditional depiction of the scene, in which magi from the east, guided by a star, found their way to Bethlehem, getting directions from Herod himself, who consulted the priests and scribes, who checked the prophets, as to the birthplace of the Messiah. And, their way confirmed by the reappearance of the star, they came to the house and saw “the Child with Mary His mother; and they fell to the ground and worshipped Him.”

Leonardo’s painting has been the subject of much speculation and debate. In 2002, the Uffizi Gallery hired Maurizio Seracini, an art diagnostician, to examine the paint surface with a view to restoring the painting without any damage. Seracini found that all that Leonardo did was the sketch and that someone else put paint over it.

In the sketch, Seracini discovered details, which had remained invisible for 500 years, such as an ox and a donkey on the right, and part of the roof of the missing stable, and many other people in the lower left corner.

The ruined pagan building, which connotes the crumbling of the ancient, pre-Christian order, suggests the Basilica of Maxentius. Legend had it that the structure would endure until a virgin gave birth (they say that the building collapsed on the night of Christ’s birth). The palm tree in the center represents Mary, the person purportedly addressed in this passage in the Song of Solomon—“You are stately as a palm tree.” To Christians, of course, the palm tree speaks of martyrdom—of triumph over death. And the other tree—a carob tree, also known as locust tree—symbolizes John the Baptist, who ate its pods, which he paired with honey.

But what of the battling horsemen?

First, the fact of the painting being unfinished. Did Leonardo leave it so on purpose?

Art has examples of famous unfinished works. Geoffrey Chaucer never completed the Canterbury Tales. J.R.R. Tolkien died without giving The Silmarillion a final, definitive form. Elizabeth Shoumatoff could not finish the portrait from life of Franklin Delano Roosevelt because he died hours after she began it. Equally uncompleted are Franz Schubert’s Unfinished Symphony and Mozart’s Requiem.

Then again, an artist might purposely give the work an unfinished look for effect—as did Donatello.

As to the magi, in his famous poem about them, instead of writing about the actual moment when the wise men found Mary and child, T.S. Eliot dwelt on the magi’s journey, its problems, its uncertainties, and the transformed lives that the three men lived afterwards.

The various, largely unknown people surrounding the Virgin Mary and her infant and the three wise men, and the raging battle at the back, speak to me of the contemporaneity of the epiphany, of Christ’s continued presence in history and constant revelation of himself to the restless world.

Towards that revelation and encounter, I must constantly make a journey, the journey of the magi. As to Leonardo’s painting, it is as if he has left the viewer a sketch, a design, a pattern, for him or her to flesh out and finish in order to arrive at a full appreciation and knowledge of the Incarnation.