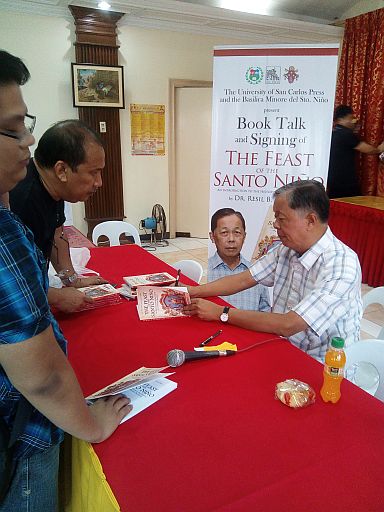

Mojares Book launch

(CDN PHOTO/ Cris Evert Lato-Ruffolo)

What events transpired between the miraculous beginnings of the Señor Santo Niño in the 1500s – when its image was found unscathed amid the ruins of a burnt coastal town in Cebu, to its present festive and widely-publicized celebration?

This is the question that renowned Cebuano writer/critic and cultural researcher Resil Mojares attempts to answer in his new book “The Feast of the Santo Niño: An Introduction to the History of a Cebuano Devotion.”

“The standard history started when Magellan arrived in our shores in 1521 and gave the Santo Niño to Humabon’s wife but it was only in 1565 when it was rediscovered (by Basque sailor Juan de Camus). This is a significant episode that most historians dwell on. And then, comes the present day celebration. You have the beginning and the present and there’s the middle that has not been talked about. There is a long history between the 17th and 19th century that we haven’t discussed. That’s a gap of knowledge of two and a half centuries,” said Mojares at the book launching held at Aula Magna of the Basilica Minore del Santo Niño de Cebu.

The book launching, which included a talk and book signing, was held last Friday, January 20, on the same day of the “Hubo” ritual of the Santo Niño de Cebu observed five days after his feast.

Mojares said the book is not a typical religious narrative of the Santo Niño.

While most of the literature pertaining to the Child Jesus looked into its beginnings and discovery and then leaps to the present day elaborate fiesta, Mojares’ The Feast of the Santo Niño endeavored to become a well-researched, complete and readable account of the history of the Santo Niño devotion.

He made this possible by providing a concise account of the evolution of the devotion to the Santo Niño at the turn of each century until it has evolved into its current form, a world-renowned event and profound Cebuano tradition.

“The realities in the 17th and 18th centuries made it unlikely for this devotion to resemble the kind that we are familiar with today because the population was very small, the economy was stagnant… there are material conditions and factors that did not support an elaborate celebration,” he told an audience composed of historians, academicians and cultural and heritage advocates.

Added to this, Mojares said, was the fact that the devotion to the Child Jesus was enmeshed in the politics of colonialism as religion was used to appease the revolting spirits of the natives.

The book is part of the Magellan Quincentennial books published by the University of San Carlos (USC) Press in preparation for the 500th anniversary of the Ferdinand Magellan expedition, according to USC Press manager Jose Eleazar Bersales.

This is why the Mojares book is not a one-time, big-time history imprint.

“This is a story that can’t be told once and for all. It has to have subsequent editions. This book is a good start,” said Mojares.