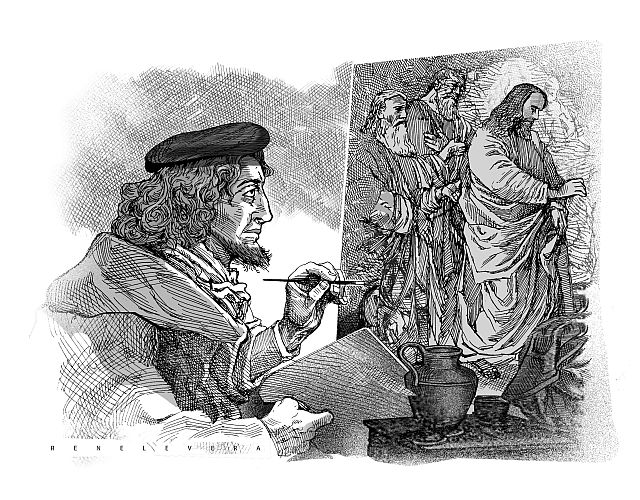

Giorgio Vasari called it Raphael’s “most beautiful and most divine” work, this painting—“The Transfiguration”—which now hangs in the art gallery of the Vatican Museums.

When Cardinal Giulio de Medici, who later became Pope Clement VII, commissioned it, he refueled the rivalry between Raphael and Michelangelo.

This was because Cardinal Giulio had likewise commissioned another painting, “The Raising of Lazarus,” for which Michelangelo would supply the drawings. The two had earlier competed with each other when they did frescoes for the papal apartments, Raphael in the Stanze (now known as the Raphael Rooms) and Michelangelo in the Sistine Chapel.

Raphael died without completing the painting, most of the work on which he had accomplished, however. When his body lay in state, the painting hung at his head.

Cardinal Giulio did not send the painting to the cathedral in France for which he had intended it as an altarpiece, and just decided to keep it in Rome.

Until Napoleon Bonaparte had his troops take it to Paris, together with every other work by Raphael, for display in the Louvre. Six years later, by reason of a treaty, Raphael’s works returned to the Vatican.

In this painting, Raphael depicts what Matthew writes about in his Gospel, about the moment when Jesus took Peter, James and John up a high mountain and there became transfigured—“his face shone like the sun and his clothes became white as light.” Moses and Elijah appeared and began conversing with Jesus. The sight astounded Jesus’ three companions, particularly Peter, who exclaimed, “Lord, it is good that we are here. If you wish, I will make three tents here, one for you, one for Moses, and one for Elijah.” But before he could finish saying this, a bright cloud cast a shadow over them, and from the cloud came a voice that said, “This is my beloved Son, with whom I am well pleased; listen to him.”

In “The Transfiguration,” Raphael brings into play his genius in handling not just movement and form but also color and light, for which he was praised as the ideal High Renaissance painter. There is dignity in his subjects, who move about in a coherent, harmonious word.

We see Christ floating against a cloud of light, joined by a similarly buoyant Moses and Elijah. On the ground, Peter, John and James cover their eyes, finding the glare too strong for staring.

Below this, Raphael includes a subplot, another scene showing the apostles unsuccessfully attempting to free a boy from demonic possession. The boy’s deliverance comes about with the arrival of the transfigured Christ, who performs a miracle. This was how Goethe summarized the two scenes:

“The two are one: below suffering, need, above, effective power, succour. Each bearing on the other, both interacting with one another.”

What did Jesus want to impart to the three apostles with his Transfiguration? That to know truth, one needs divine light.

St. Augustine tells us that God can give either just the information or the insight into the truth of the information. For instance, the apostles saw the humanity of Christ with their own eyes, but in the Transformation were given an insight into the truth, the divinity of Christ. The first knowledge naturally comes to us through our senses, the second, with the aid of God’s grace.

And perhaps this is what Raphael wishes to convey with the two dimensions in his painting—the upper, in which his brush approximates the pure light and truth of God, and the lower, the world of sensory light, in which we helplessly thrash about in a sea of change and confusion and suffering, always longing for the healing power of comprehension, for clarity, in the transfigured face of Christ.