I find in this poem, “Like the Water,” by Wendell Berry, meanings that I can only describe as transcendental.

Like the water

of a deep stream,

love is always too much.

We did not make it.

Though we drink till we burst,

we cannot have it all,

or want it all.

In its abundance

it survives our thirst.

In the evening we come down to the shore

to drink our fill,

and sleep,

while it flows

through the regions of the dark.

It does not hold us,

except we keep returning to its rich waters

thirsty.

We enter,

willing to die,

into the commonwealth of its joy.

Clearly, the poem has to do with love, and is therefore a love poem. But, unlike traditional love poems, it does not address a loved one, at least not directly. It ruminates on love, with the one speaking drawing another or others into the reflection, proposing a concept of love for them to accept or refuse.

The poem equates love with water, “like the water of a deep stream,” and goes on to list their common qualities. First, we did not bring love or water into existence—water and love come to us as gifts, which are “excessive,” more abundant than we can imagine. We may drink all the water that we need, and not consume it—“In its abundance / it survives our thirst.” And love is no different, especially God’s love, his mercy, his compassion, which is not exhausted but, according to the Book of Lamentations, is renewed every morning.

“In the evening we come down to the shore / to drink our fill, / and sleep, / while it flows / through the regions of the dark.” What does this mean? Once, in the country, with their kerosene cans and pails and bamboo poles, the folk would go to a stream to fetch water, their supply for the night and the next morning, for cooking and washing. And having done with supper, after conversation (and in our case singing), the family retired for the night. What drove the folk to do these things could not be anything other than love—the love of family, the love between husband and wife, between parents and children, which, like the water in the stream, continues to flow even during sleep. And yet we cannot own either love or water, unless we make it our own and drink of it, unless we keep our thirst, our desire for it alive.

The poem ends—“We enter, / willing to die, into the commonwealth of its joy.” What a beautiful line! Here, water attains a transcendent status, becomes a symbol of heaven (“the commonwealth of joy”), which we, making little of the prospect of death, can enter through love.

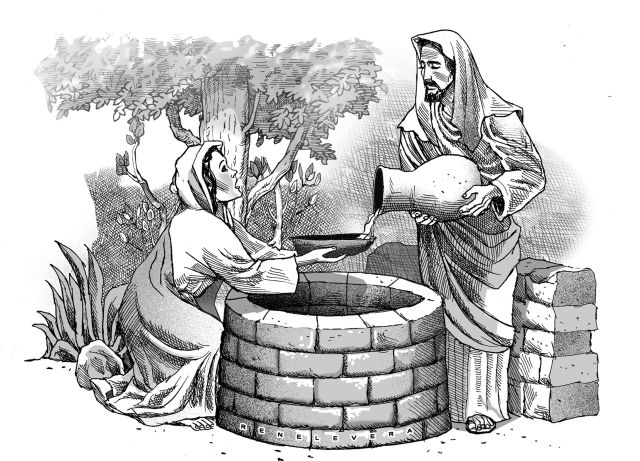

This is how I read the poem. It reminds me of the account, in the Gospel of John, of Jesus’ encounter with a Samaritan woman. It was noontime, tired and alone (his companions having gone into the town to buy food), Jesus sat by a well.

A woman came to draw water and Jesus asked her to give him a drink. This took her aback—Jesus was a Jew and the Samaritans did not have dealings with Jews. Instead, Jesus said to her, “If you knew the gift of God and who is saying to you, ‘Give me a drink,’ you would have asked him and he would have given you living water.”

Then Jesus added, alluding to the water in the well, believed to be Jacob’s well and sacred to the Samaritans, “Everyone who drinks this water will be thirsty again; but whoever drinks the water I shall give will never thirst; the water I shall give will become in him a spring of water welling up to eternal life.” Her curiosity aroused and ever the practical person, the woman replied, “Sir, give me this water, so that I may not be thirsty or have to keep coming here to draw water.”

In the end, the encounter led to the woman’s conversion (she had had multiple partners) and conviction, which Jesus confirmed, that Jesus was the Messiah.

In the discourse between Jesus and the Samaritan woman, the water in the well led to the living water, which quenches the thirst once and for all, and becomes in the person drinking it a “spring of water welling up to eternal life.”

Wendell Berry got it right. There is no such water, none that can take us to “the commonwealth of joy”—except love.