In Padua, northern Italy, at the Cappella Scrovegni (Arena Chapel), we find frescoes done by Giotto portraying scenes from the life of Christ. One of them depicts an incident narrated in the Gospel of John, about the raising of Lazarus from the dead.

Lazarus lived in Bethany with his sisters Mary and Martha. They were all close friends of Jesus. When Lazarus got sick, his sisters sent word to Jesus informing him of his illness. But instead of rushing to his side, Jesus waited for a few more days before deciding to go to Bethany. By this time, Lazarus had died. Jesus, however, made little of his death—“Our friend Lazarus is asleep, but I am going to awaken him.”

When he arrived in Bethany, Martha told him, “Lord, if you had been here, my brother would not have died. [But] even now I know that whatever you ask of God, God will give you.” Jesus assured her, “Your brother will rise.” To which Martha replied, “I know he will rise, in the resurrection on the last day.” And then Jesus told her, “I am the resurrection and the life; whoever believes in me, even if he dies, will live, and everyone who lives and believes in me will never die. Do you believe this?” She said to him, “Yes, Lord. I have come to believe that you are the Messiah, the Son of God, the one who is coming into the world.”

A tearful Mary, Martha’s sister, and her companions came and Jesus asked to be taken to where they had laid the body of Lazarus. Of this moment John writes, “And Jesus wept.” Which sight moved the Jews to exclaim, “See how he loved him.”

A stone lay across the cave which served as Lazarus’ tomb. Jesus said, “Take away the stone.” But Martha protested, “Lord by now there will be stench; he has been dead for four days.” Jesus said to her, “Did I not tell you that if you believe you will see the glory of God?” So they took away the stone and Jesus raised his eyes and said, “Father, I thank you for hearing me. I know that you always hear me; but because of the crowd here I have said this, that they may believe that you sent me.” And when he had said this, he cried out in a loud voice, “Lazarus, come out!” The dead man came out, his hand and foot tied with burial bands, his face wrapped in a cloth. Jesus said to them, ‘Untie him and let him go.’” John ended his account with these words—“Now many of the Jews who had come to Mary and seen what he had done began to believe in him.”

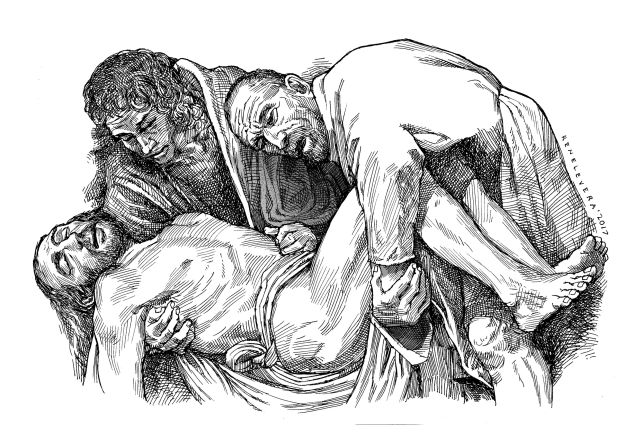

Aside from Giotto, other artists painted the raising of Lazarus, notably, Caravaggio and Rembrandt. Caravaggio employed his superb handling of light and sharp eye for detail to relate the story of Lazarus in a powerful, dramatic manner. Supported by his sisters and friends, Lazarus raises one hand to reach out towards Christ, while the other hand hangs loosely at his side. That Caravaggio had a newly buried body exhumed for his painting might be an urban legend, but was not improbable, considering his wild ways.

Rembrandt, on the other hand, focuses on the moment when Lazarus awakens from death inside the cave of his entombment, which is dark except for the portion around a torchlight. The painting emits a spiritual energy, with most of the illumination falling on the faces of those concerned, and on the right hand of Jesus raised in command.

I find Giotto’s rendition of special interest. A contemporary of Dante, Giotto broke away from the prevalent Byzantine style of his day and began what Vasari called “the great art of painting as we know it today, introducing the technique of drawing accurately from life, which had been neglected for more than two hundred years.”

Hence, instead of a flat, abstract depiction, Giotto gives us in “Raising of Lazarus” a work that depicts real people with actual emotions in a scene that hews to life. For instance, the sheet that covers Lazarus and the robes of the people around him fall with natural folds, and the look of amazement in the faces witnessing the miracle comes across convincingly.

The work is a clean and delightful portrayal of the Gospel incident, in a setting of stunning color, consistent with a Jesus determined to display the power and the glory of God through his action.

The paintings of Caravaggio, Rembrandt and Giotto show a powerful Jesus, acting with authority, the authority of God. Still, we should not forget that, before he raised Lazarus, Jesus wept. Of this C. S. Lewis writes, “[W}e follow One who stood and wept at the grave of Lazarus—not surely because He was grieved that Mary and Martha wept, and sorrowed for their lack of faith (though some thus interpret), but because death, the punishment of sin, is even more horrible in his eyes than in ours.”