The Argentinian writer Jorge Luis Borges wrote a story entitled, “The Gospel according to Mark.” It tells of Baltasar Espinosa, a medical student from Buenos Aires, who went to a ranch in the country upon the invitation of his cousin Daniel.

In that ranch lived the overseer Gutre, his son and a girl “of uncertain paternity,” all of them primitive, rough and uncommunicative.

After a few days, Daniel returned to the capital for some business, leaving Espinosa alone in the ranch. Heavy rains fell, causing the river to overflow and kill the animals and threaten to wash away the overseer’s quarters.

Espinosa decided to let the Gutres stay in the main house. They ate together and became physically close, but Espinosa found it difficult to converse with them.

So, to perk up the after-dinner talk, he read to them a few chapters from a book lying about.

The Gutres showed no interest. Espinosa found a Bible in English and, purely as an exercise in translation, read from it too, beginning with the Gospel of Mark.

Surprisingly, this fired up the attention of the Gutres, who after that would not miss any session. When Espinosa finished the Gospel of Mark, the elder Gutre asked him to read it again so they could understand it better.

That night, Espinosa dreamt of the Flood.

The hammering in the construction of Noah’s ark, which he had taken for thunder, woke him up.

Heavier rains came. One night Espinosa heard a knock on the door and, when he opened it, found the girl, who went in to sleep with him. (Earlier, Espinosa had treated her pet lamb, which had cut itself on a barbed wire.)

The next day, the father asked Espinosa if Christ allowed himself to be killed to save all of mankind. A freethinker, Espinosa played along and said, “Yes. To save us all from hell,” explaining hell as “a place underground where souls burn and burn.”

“And those that drove in the nails were also saved?” Gutre asked.

Despite his uncertain knowledge of theology, Espinosa said yes.

After lunch, they asked him to read the last chapters of Mark again. A persistent hammering and certain premonitions disturbed Espinosa’s siesta.

In the afternoon, Espinosa saw that the waters had receded. The three Gutres kept following him and asked for his blessing, after which they cursed and spat on him, and pushed him towards the back of the house.

“The girl was crying. Espinosa knew what to expect on the other side of the door. When they opened it, he saw the heavens. A bird shrieked. ‘A goldfinch,’ he thought.

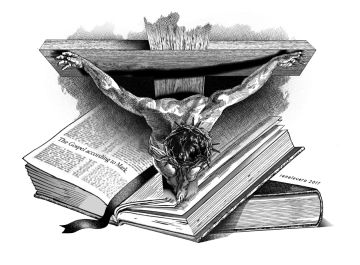

The shed was without a roof; they had torn out the beams to build the cross.”

The story appeared in Borges’ collection, “Dr. Brodie’s Report,” published in 1970. It falls under the genre, fantasy. I consider it a variant of the Borgesian conundrum, defined as the question, “Whether the writer writes the story, or it writes him.”

Similarly, in “The Gospel according to Mark,” we can ask whether the reader becomes the one read about, or the one read about becomes the reader.

Because to the primitive and unlettered Gutres, Espinosa turned into Christ himself, and his purely academic reading of the Gospel of Mark convinced them of the need to crucify him.

Although simply told, the story is complicated. It has layered themes. Still we can take it as a cautionary tale, about a man conveying spiritual truths to the uneducated, doing this without sincerity and with only a skimpy comprehension of their significance, and then completely leaving to the simple folk the delicate task of interpretation.

How could they understand, for instance, the question, why did Christ die on the cross? Mostly, this requires of one a lifetime of study and prayer.

Indeed, the great philosophers and theologians of old grappled with it day and night. To Anselm of Canterbury, because of sin, man owes the just God a debt of honor, which through his death Christ more than paid for, earning for man the avoidance of punishment. To Thomas Aquinas, Christ’s death mends the damage done to the sinner by sin and restores him to a state of harmony with God.

In fact, we are saved, not by the cross alone, but, as the Catechism of the Catholic Church puts it, by Christ’s whole life, by all the stages of it. Christ’s life is “a mystery of redemption.” His mission, that in him we may recover what we lost in Adam — our being in the image and likeness of God.