In his book “The Poetry Home Repair Manual,” Ted Kooser cites this sentence from Tomas Tranströmer’s poem “The Couple” to illustrate a successful simile:

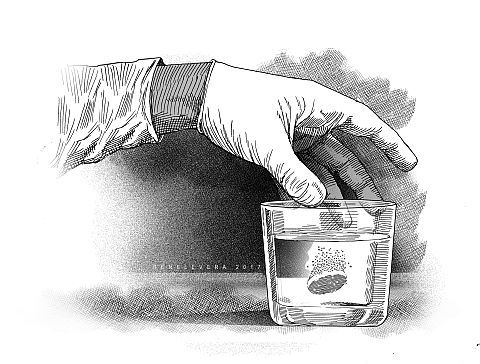

They turn the light off, and its white globe glows an instant and then dissolves, like a tablet in a glass of darkness.

Here Tranströmer compares a fading light bulb to a tablet dissolving in a glass of water. When turned off, bulbs do not instantly lose their light but continue to glow for a second or two. We do not usually associate a bulb with a tablet, however; between them, there are more differences than similarities. But whatever little they have in common, Tranströmer utilizes to maximum effect — the fact that both the lighted bulb and tablet are white, and the fact that the bulb continues to glow as its white light goes out, in the same way that a white tablet takes a moment or two to fizz and dissolve in water.

Kooser comments that “to suggest that a fading light bulb is like a dissolving tablet is more of a leap—almost, I think, an epiphany.”

Epiphany? Isn’t that the manifestation or revelation of God? Kooser overdoes it a little bit. Still, the mention of epiphany calls up an incident in the Gospel of Matthew, which likewise has to do with light.

Matthew writes:

After six days Jesus took Peter, James, and John his brother, and led them up a high mountain by themselves.

And he was transfigured before them; his face shone like the sun and his clothes became white as light.

And behold, Moses and Elijah appeared to them, conversing with him.

Then Peter said to Jesus in reply, “Lord, it is good that we are here. If you wish, I will make three tents here, one for you, one for Moses, and one for Elijah.”

While he was still speaking, behold, a bright cloud cast a shadow over them, then from the cloud came a voice that said, “This is my beloved Son, with whom I am well pleased; listen to him.”

When the disciples heard this, they fell prostrate and were very much afraid.

But Jesus came and touched them, saying, “Rise, and do not be afraid.”

And when the disciples raised their eyes, they saw no one else but Jesus alone.

The light mentioned here is, of course, no fading light bulb. What Matthew describes is the transfiguration of Jesus in the presence of the three disciples — Peter, James and John. Jesus’ face “shone like the sun and his clothes became white as light.”

Thomas Aquinas remarks that in his transfiguration, Christ miraculously poured out the glory of his soul into his body. The clarity of his body which the disciples saw was just a foretaste of the glory that Christ would gain at his resurrection.

But for what purpose was the Transfiguration? Aquinas answers, “Our Lord, after foretelling His Passion to His disciples, had exhorted them to follow the path of His sufferings. Now, in order that anyone (can) go straight along a road, he must have some knowledge of the end: thus an archer will not shoot the arrow straight unless he first see the target. … Above all is this necessary when hard and rough is the road, heavy the going, but delightful the end. … Therefore, it was fitting that he should show the disciples the glory of His clarity (which is to be transfigured), to which He will configure those who are His.”

Thomas Aquinas quotes the Venerable Bede as well: “By His loving foresight He allowed them to taste for a short time the contemplation of eternal joy, so that they might bear persecution bravely.”

I remember the night before our daughter died in a sea accident. Our conversation was extraordinarily lively during dinner, and we were laughing our hearts out at her jokes. It seemed as if we were being prepared for the next day’s tragedy. And, of course, any remembrance of good times spent together would never lessen the pain one feels at the loss of a loved one, although in due time it adds to the healing.

In the case of the disciples, who were about to see their teacher’s life apparently ending in failure and to face the prospect of theirs reaching the same conclusion, the sight of him in the brightness of glory would prepare them to endure until the morning of Easter, the thought of Christ’s transfiguration remaining with them as more than an afterimage, and more like a glowing tablet that continues to fizz without dissolving in the dark waters of despair.