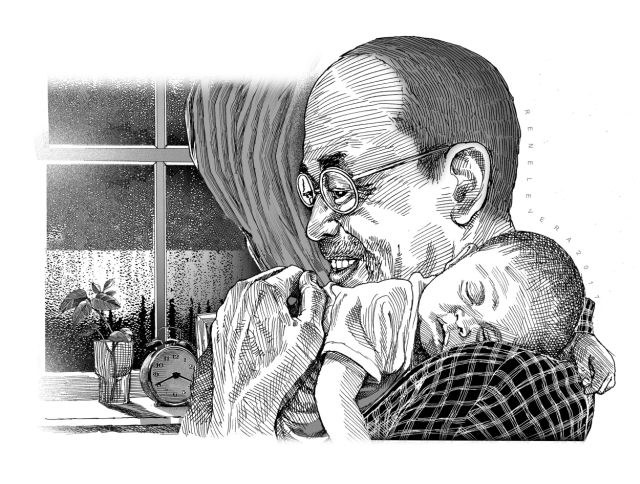

Every morning, right after sunrise, the wife and I wake up to the call of our daughter. Without delay, I would open the door to let her in, and she would hand her one-year-old infant over to me and return to the next house, where she and her husband reside. We have agreed on this arrangement to allow them to extend their sleep, interrupted every now and then during the night by the baby’s needs.

The wife and I have agreed that I should attend to the baby first, so she can have an extra wink or two (usually two). To keep the little girl busy, I would play nursery rhymes on TV until the wife takes over, and waits for the nursemaid to arrive with the baby’s breakfast.

Aside from nursery rhymes, I would show video lessons on the alphabet and numbers. I suspect that, since we have carried on like this long enough, the little one now recognizes several letters and numerals.

In no time she will know how to count, first her fingers and next the objects lying around. And then she will move on to the basic operations. I recall how, years ago, I taught a nephew how to subtract by getting him to eat two bananas out of three (reserving the last for myself).

Of course, school will do the rest to equip her with the knowledge of numbers that living in society requires, especially since the latter puts a premium on quantity. As an adult she will earn and own property and manage her acquisitions and bank accounts — and, as with everyone else, counting — the questions how many and how much — would come into most every activity.

Science teaches us that we can measure everything, an outlook that has grown into an ideology that considers only those that can be measured as real. Which is, of course, false.

Peter displayed a similarly measuring mind when, as we read in Matthew’s Gospel, he asked Jesus, “Lord, if my brother sins against me, how often must I forgive him? As many as seven times?” Jesus’ answer in effect urged him, when it came to grace, to unlearn all the math that he had assimilated. “I say to you, not seven times but seventy-seven times.”

Jesus went on to tell a parable about a servant who was called by his master to settle his account, which he could not pay, and for which, therefore, he was to be sold together with his wife, children and possessions. When he begged for mercy, his master forgave him his loan.

But he himself did not show any mercy to his fellow servant who owed him a much lesser amount. He put the latter in prison until he could pay his debt. When word of this reached him, the master was enraged, “You wicked servant! I forgave you your entire debt because you begged me to. Should you not have had pity on your fellow servant, as I had pity on you?” The master then handed him over to the torturers until he should pay back his whole debt.

“So will my heavenly Father do to you,” said Jesus, “unless each of you forgives his brother from his heart.”

Christianity urges us to defy numbers. With just five loaves and two fishes, Jesus fed 5,000 people. As followers of Christ, we believe in the miraculous and willingly play down appearances.

Even modern mathematics goes beyond numbers, and uses infinity to solve a horde of problems. One can count without end, the sequence of numbers being unlimited.

Christ commands us to love without measure, in effect to disregard a man or woman’s measurements — the height and width, the vital statistics, the physical beauty — and to go directly to the person’s soul. This is the only way that we can love the unlovable.

A saying puts it nicely — “If only our eyes saw souls instead of bodies, how very different our ideals of beauty would be.”

In the parable, the master looked beyond the servant’s cash value, his debt, and took pity on him. But that servant could not treat a fellow servant with a similar sympathy, because he saw the latter as measurable, as having no more value than the amount of his debt.

Time can erase one’s memory. When one reaches old age, one might not recognize numbers and forget how to count. Indeed, one could get so old as to fail to remember people, their names and faces. But I’m sure of this, that, if one forgets every single thing, there will always remain an item that one will recognize and respond to — compassion.