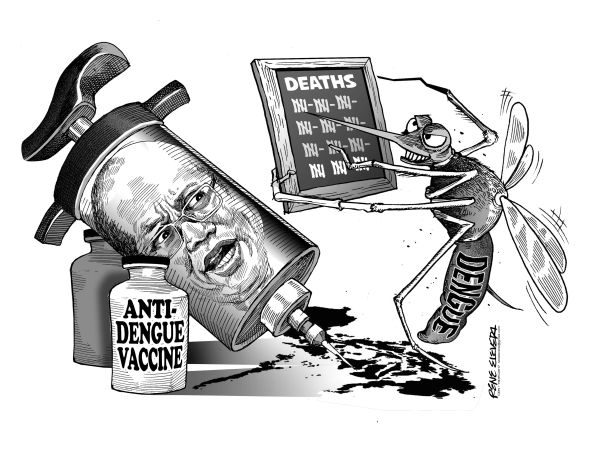

As the former president, any failure or fiasco committed by his administration ultimately falls on his shoulders. But while Aquino admitted that he approved the acquisition and distribution of Dengvaxia in the last year of his term, he did so out of the firm belief that he was protecting the welfare of Filipino children, a growing number of whom fall prey to dengue every year.

“The choice is simple: We can implement at this point in time or wait for at least a year as a minimum and expose our people to a risk that could have been prevented because of this vaccine,” Aquino said referring to the Dengvaxia vaccine developed by Sanofi Pasteur.

As most often cited, hindsight is 20/20 and Mr. Aquino himself said no one from his past administration to this day objected to the use of the vaccine on the country’s more than 500,000 children, including more than 100,000 in Cebu province.

In a remarkably unusual development, considering that Congress is an administration supermajority, a lot of senators stood by Aquino’s statement which is likely a testament to his integrity as far as this case is concerned even if Congress has yet to finish its investigation into the fiasco.

What is clear now — certain officials of the former administration bear responsibility for the “unbelievable” haste as Sen. Richard Gordon described in approving the purchase and distribution of Dengvaxia and should thus be held accountable.

All this handwringing aside, the onus of responsibility still lies in former Health Secretary Jeanette Guarin, who can in her former capacity lobby for the acquisition of Dengvaxia even if Sanofi has yet to finish post clinical trials on the vaccine.

In essence, the root cause of the fiasco was what one Dr. Anthony Dans of the National Academy of Science and Technology (NAST) called “bad science” in which the Formulary Executive Council knew and pointed out the problems posed by Dengvaxia, but these were ignored by health officials like former Health Secretary Paulyn Ubial.

Ubial, who figured in a heated argument with Guarin, claimed that some lawmakers including Guarin’s husband pressured her into approving the release of third batch of Dengvaxia vaccine despite her reservations.

But maybe even then, it was hard to reconcile such reservations and findings about Dengvaxia’s potentially harmful effects with the demands of politicians and the children who are vulnerable to the deadly dengue virus.

Therein lies the dilemma: Granted that officials like Aquino may have the best intentions but when something had yet to be fully tested, it is not advisable to proceed with its implementation knowing that the risks far outweigh the benefits.

It remains to be seen if Aquino and his former officials will face any charges for this fiasco, but while well-meaning, above board intentions may not result in their eventual prosecution, it doesn’t spare them the accountability and responsibility for exposing hundreds of thousands of children to the danger of suffering tenfold and possibly dying from dengue.