In 1595, while imprisoned in the Tower of London to await his execution, the Jesuit priest and poet Robert Southwell, a cousin of William Shakespeare, wrote a Christmas poem, entitled, “The Burning Babe.” Ben Jonson envied Southwell for it, saying that had he written the poem himself, he would have been content to destroy many of his own writing.

Elizabeth I of England had outlawed the Catholic faith. For six years, Southwell had secretly engaged in priestly activity, until the government forces arrested and tortured him, and in time had him drawn by a horse to the place of execution, hanged him and disemboweled his body. In 1970, Pope Paul VI canonized him as a saint, one of the forty Catholic martyrs of England and Wales.

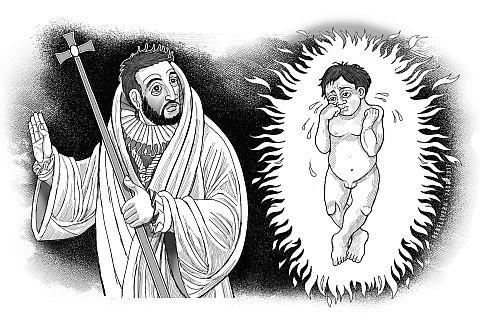

The incident in the poem happened on a winter’s night. While shivering in the cold, the speaker suddenly felt heat, which strangely caused his heart to glow. He looked up and in the air saw a burning baby shedding tears, which tears, rather than quench, only fed the flames.

The baby lamented that, despite that it had just been born, already it was in flames, and yet nobody had come to warm his heart with and feel the fire. The baby described its breast as a furnace, which was fueled by sharp thorns — the fire, love; the smoke, sighs; the ashes, shame and scorns. It was Justice that laid the fuel, and Mercy that blew the coals, and the metal being forged in the furnace were “men’s defiled souls.” The baby was on fire for their good, so it could “melt into a bath to wash them in my blood.”

And then the baby vanished as suddenly as it had appeared. At that moment, the speaker remembered that it was Christmas Day.

With this He vanish’d out of sight

And swiftly shrunk away,

And straight I callèd unto mind

That it was Christmas Day.

“The Burning Babe” is an allegorical poem. It presents the idea that, from the very first moment of his existence, from the time of his birth (and, for that matter, of his conception), Jesus, the Son of God, burned with and suffered for his love for all of us, sinners, whom he seeks to reform with his Justice and Mercy.

In a way, Southwell foreshadowed the Metaphysical poets of 17th century England, such as John Donne, George Herbert and Richard Crashaw, whose works bear his influence in their wit and use of intricate imagery (called conceit) in handling mostly religious themes. We find this influence as well on Shakespeare himself, to whom Southwell dedicated his collection of poems, “St. Peter’s Complaint” (“to my worthy good cosen Maister W. S.”).

Consider, for instance, this remark of Macbeth:

And Pity, like a naked new-born babe,

Striding the blast, or heaven’s Cherubins, hors’d

Upon the sightless couriers of the air,

Shall blow the horrid deed in every eye

That tears shall drown the wind.

It is not farfetched to say that Southwell wrote this poem in contemplation of his martyrdom. Which explains why he conflated Christ’s Nativity with his Passion. Southwell considered it the fate of every Catholic in the England of his time to die for his faith, for whom in effect birth was death, and suggested that in the winter night of his fear, he should seek warmth by drawing close to the fire of Christmas, the Burning Babe, and obtain cleansing from his tears.