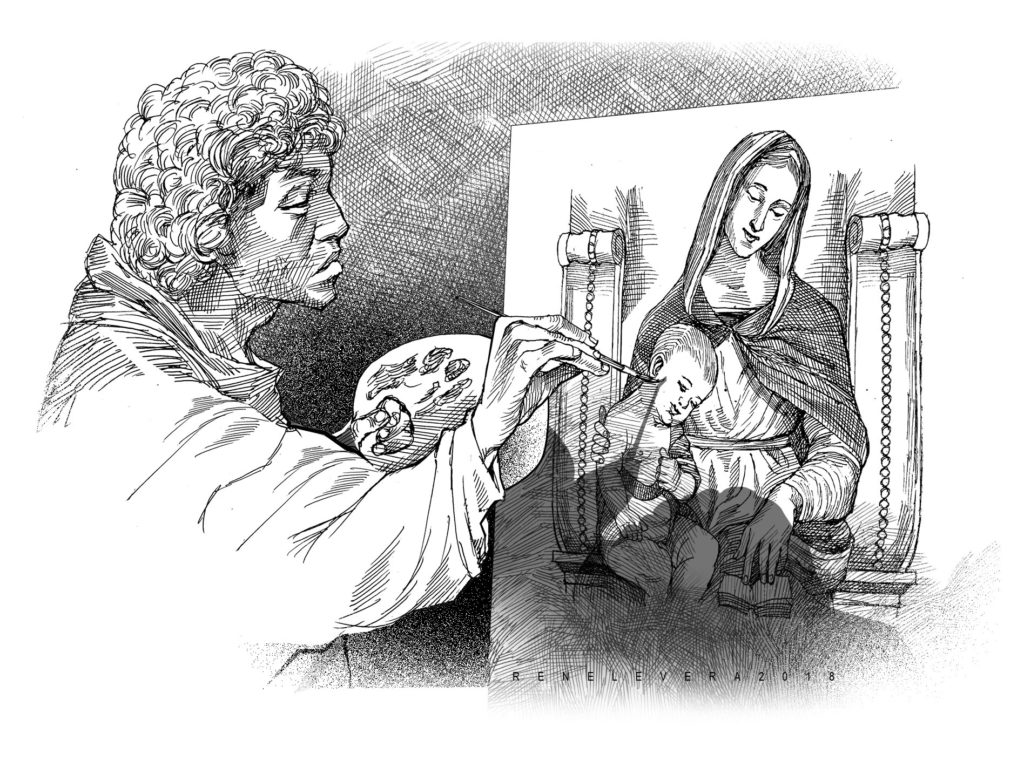

John Ruskin considered Raphael’s Ansidei Madonna “one of the most perfect pictures of the world.”

Raphael was in his early twenties when he did the painting, which Niccolò Ansidei had commissioned for a family chapel in honor of St. Nicholas in the church of San Fiorenzo in Perugia, Italy.

Hence, the label, “Ansidei Madonna.”

The painting now hangs in the National Gallery in London. It depicts the Virgin Mary, who is rather formally seated on a wooden throne, with the Child Jesus on her lap, beside an open book, a small one, to which she points with her left hand, as though showing something to the child.

An adult John the Baptist stands on her right, and on her left, St. Nicholas, who is reading a book.

At the back, a magnificent arch vaults over them. The throne bears the inscription, Salve Mater Christi (Hail, Mother of Christ).

Why did Ruskin speak highly of this work?

Here, no doubt, the artist strove for deeper than a natural, realistic portrayal because he omitted to put arms to the rather humble throne, which he set on too steep a level.

Clearly, the value of this well-executed painting lies in its serenity, inviting the viewer to regard its spiritual rather than physical qualities. A blissful, radiant painting without any shabbiness.

How composed the Madonna looks and how tenderly she attends to her child, who rests on his mother’s lap with absolute content and trust, the attitude that, as Jesus himself said in the Gospel of Matthew, one must have if one desires to be great in the kingdom of heaven.

The disciples had asked Jesus, “Who is the greatest in the kingdom of heaven?”

Jesus then called a child over, placed it in their midst, and said, “Amen, I say to you, unless you turn and become like children, you will not enter the kingdom of heaven.

Whoever humbles himself like this child is the greatest in the kingdom of heaven.”

eing first in Christian terms is a paradox — it is to be the least and the last.

Just as to acquire life one must die, in the same way that a seed must fall to the ground and break up before it can put out its roots and leaves.

The image of Christ as infant is for me an image of God’s emptying — God’s plumbing the depths of human helplessness so as to fill it with the power of God. We have to drain the tank of its stale contents in order to fill it with fresh, clean water.

Of course, at no moment did Jesus cease to be God. He remained the omniscient and omnipotent one even as a baby in the arms of his mother.

Of this the popular image of the Santo Niño reminds us — the Christ Child wearing a crown, dressed in kingly robes, holding a globe in one hand and a scepter in the other, Mary’s child come to judge and rule the world at the end of time.

God assuming helplessness in Jesus’ infancy continues in the Eucharist, in which He is present in the form of bread and wine, unprotected from the irreverent and sacrilegious acts of non-believers, and even of believers who are uncaring and indifferent.

God offers Himself as food to sustain us on our spiritual journey.

As food to be consumed, He hides his splendor in the ordinariness of bread and wine.

Raphael’s painting points to the paradox of Christ — Mary seated on a humble throne without arms, which she does not need because she is attending to her infant, who completely abandons himself to her and yields his status as God to show us the folly of human wisdom in seeking power in power. The obvious is often misleading.

As Viktor Frankl said, “It is the very pursuit of happiness that thwarts happiness.”