As far as I know, not one of the famous artists, including those who favored biblical themes, had a go at it, notwithstanding that, among Jesus’ miracles, the healing of lepers had prominence.

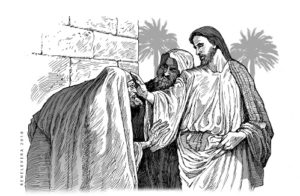

Except for one artist, the Frenchman Jean-Marie Melchior Doze, who lived towards the turn of the last century. In 1864, he did a painting, entitled, “Christ Cleansing a Leper.”

Matthew, Mark and Luke have each an account of Jesus healing a leper or lepers. Mark writes that a leprous person had come to Jesus and on his knees begged of him to make him clean. Jesus took pity, touched him and said, “Be made clean,” and at once the leprosy left him.

Jesus cautioned him about telling others about the incident. He moreover directed the man to go to a priest and perform the rite required by Moses for the cleansing of lepers. Instead, the man went about telling people about his healing. As a consequence, Jesus could no longer come out openly.

Nonetheless, although he confined himself to secluded places, the crowd continued coming to him.

In his painting, Doze depicts Jesus dealing with the now healed leper, who stays on his knees, urging him to do the things required by the Mosaic Law of those who had recovered from the disease and admonishing him not to publicize the matter.

All the while a crowd of men and women mill about. The painting conveys action in a compelling manner with people in different positions, bending over, looking upon and helping the leper, and in lordly color pulls off a dynamic portrayal of the biblical scene.

Poets, too, have largedly avoided the topic of leprosy. If they decided to write about it at all, the result could turn out gruesome, as in Algernon Charles Swinburne’s poem, “The Leper,” in which a necrophiliac speaker expresses his romantic obsession with a beautiful woman who has leprosy, and who turns out to be dead.

A poem by Herbert Nehrlich, a German doctor, is closer to the target.

She had been diagnosed and sent away,

the colony they said would be a home,

all those who caught and did not have the genes to fight the bugs,

they’d be recorded in the ledger of the State, as Hansenites.

Forever gone, outcast, with sores and swollen joints,

and dying nerves that made you drop the cigarettes

and pens with which to write your tale,

recording all events and those you felt would come

to claim your soul and take you off into the bowels of

the place we know as Hell.

Almost imagistic in approach, the poem does little more than describe the effects of leprosy on the person, the sores, the swelling, the numbness and dying nerves, and the social and psychological consequences of the decease.

In Leviticus, a priest had to inspect the leper. If, after a time of monitoring, he found that the condition did not improve, he would declare the sick man as “unclean.” Once so declared, the latter had to tear up his clothes, cover his upper lip and go about crying, “Unclean, unclean,” and had to live away from everyone else.

Obviously, both Jesus and the leper violated the Law of Moses—in that the leper approached Jesus and Jesus touched him.

I read about a somewhat similar incident in the life of St. Francis. One day, while riding his horse, Francis met a leper. He felt revulsion at the sight of the man. Still, he dismounted, gave the leper a coin and kissed his hand, and went on his way. But the disgust stayed with him.

After a few days, to completely conquerhimself, he went to a hospice of lepers with a large sum of money. He gave alms to and kissed the hand of each of the inmates.

Where before he would avert his eyes and held his nose at the presence of lepers, this time, seeing and touching them gave him a feeling of delight. God had given him the grace of love and humble service for the outcasts.

How I fall short of Francis’ standard. Yes, I try to be charitable to the wretched and miserable. And yet, whenever our car stops on the street and a beggar approaches to ask for money, I would give him a coin, dropping it into his palm, making sure that I do not touch his grimy hand.