PAREDES

Among artist-friends, he was simply called Billy, or Sir Billy by those of us who were much younger and looked up to him as some kind of patriarch.

He was always glad to meet fellow Bisaya, perhaps delighted at the opportunity to be able to converse with them in Binisaya or Cebuano.

He always talked about his hometown in Tagbilaran, growing up there with parents who were both active in the guerrilla movement during the Second World War.

He recalled his visits to nearby Cebu and his short stay here right after the war before he moved to Manila.

I first met Sir Billy or Napoleon Abueva during the Visayas Visual Arts Exhibit Conference (VIVA ExCon) when it was held in Tacloban City in 2000.

The National Artist for Sculpture was one of the senior Visayan artists who were invited as special guests to give inspirational talk to younger contemporary artists.

And to all of us who knew his great contribution in the emergence of modern sculpture in the Philippines during the postwar years, Sir Billy was more of a rock star.

And yet, in that intimate gathering of artists held in a government center, Sir Billy’s unassuming presence belied his status.

Anyone could just join him have coffee at his table and strike a conversation, which was easier for us Cebuanos.

I recall asking too many questions as I intended to write about him when I return to Cebu.

The second time I met Sir Billy was when few years later the National Commission for Culture and the Arts (NCCA) brought him to Cebu as part of a nationwide tour of National Artists in different disciplines in order that ordinary Filipinos would be able to meet them in person and be familiar with their work.

I remember attending a separate workshop with the late Edith Tiempo, the poet from Dumaguete who was recognized as a National Artist for Literature.

The NCCA brought Napoleon Abueva to SM City Cebu art gallery in what would be an artist’s version of a celebrity meet-up at a mall. A small exhibition of his work was mounted with curator’s notes on display alongside them.

But at the center of the gallery was a small work area with big pile of modeling clay, wire armatures, and molding tools.

Across it was a group of chairs so people could sit and just watch the National Artist work.

Sir Billy just stayed there for the whole day and made a clay sculpture demo for walk-in mall-goers, and guests, most of whom were students and fellow artists in Cebu.

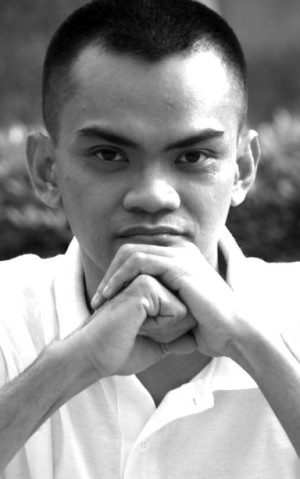

While Sir Billy was giving a talk to a small audience of students and artists, some of us started making sketches of him.

After the talk, people asked him to pose with them for photos and for his autographs.

Those of us who made sketches of him showed our still unsigned work.

When it was my turn, I asked him to autograph my quick pencil sketch of him.

“Basig abi nila ako nag-drawing ani kung pirmahan nako,” he said jokingly.

But he did sign my drawing and I later affixed mine next to it.

While I have taken some photos of him during the VIVA Excon in Tacloban, that sketch with the autograph of the subject remains my most precious souvenir of my encounters with the National Artist.

I cherish it even more now after learning about the artist’s passing last Friday.

About a year after I met Sir Billy in Tacloban, I joined the terracotta sculpture workshop under Julie Lluch, who is also a famous sculptor, working mostly in ceramics.

I have since started making my own clay sculptures after that workshop using terracotta from Liloan, which is not far from where I live. Recently, most of my work are in wood relief sculptures, and I admit not a few times did I look at pictures of the work of Napoleon Abueva for inspiration.

Sculpture is not a very popular art in the Philippines.

There are few sculptors in the National Artists pantheon. Perhaps, this is due to the fact that materials and equipment could be very expensive.

And, in the case of metal sculpture, it often relies on some supporting industry, like a good foundry or a well-equipped machine shop.

Right now, I only know of one commercial foundry that is able to cast metal in Cebu.

And the cost of casting, say a bust of bronze, is too prohibitive for a local artist.

As public art remains the most practical purpose of monumental sculpture, it requires institutional patronage, of which so much remains wanting in the Philippines. This also explains why only one school in the Philippines is offering sculpture as a course in fine arts, and I heard there were times when only one student is enrolled in the whole year.

In contrast, in countries like China, which lavishly spend for state-commissioned public art, sculpture is the most lucrative art and a lot of aspiring artists would choose to major in sculpture at the art schools.

Indeed, the lifelong struggle of Napoleon Abueva for sculpture to be recognized and appreciated in the Philippines is still not over.

We long to see the day when there are more locally-made monuments and sculptures in parks, malls, churches, and other public places than there are billboards and other advertising installations.

When the day comes, Sir Billy, our very own Bisdak National Artist, will be smiling somewhere in art heaven.