In 1789, William Blake came out with “Songs of Innocence,” a collection of 19 poems, to which, five years later, he added a new set of poems and called the expanded collection, “Songs of Innocence and of Experience.”

Included in “Songs of Innocence” is “The Shepherd,” a poem of two four-line stanzas.

The Shepherd

How sweet is the Shepherd’s sweet lot

From the morn to the evening he strays;

He shall follow his sheep all the day,

And his tongue shall be filled with praise.

For he hears the lamb’s innocent call,

And he hears the ewe’s tender reply;

He is watchful while they are in peace,

For they know when their Shepherd is nigh.

If the poem were an advertisement seeking people to work as shepherds, there would be numerous takers and the position would be filled in no time. The shepherd in the poem has absolutely no cares. During the day he goes wherever he wants and does nothing but utter praises, most probably to the Lord. Quite strangely, instead of the sheep following him, he follows the sheep. Perhaps the animals are more intelligent and have a better sense of direction, or else the shepherd finds greater excitement in emulating the irresponsible freedom of animals than in exercising his own freedom, for which he has to account anyway.

When the sheep are “in peace,” which we may take to mean at night, when they are asleep after an uneventful day, the shepherd typically does not do anything (such as ensure that they are in good shape). Anyway, he appears to find reassurance in listening to the lamb’s “innocent call” and the ewe’s “tender reply,” clearly a reference to the soft sounds a lamb makes when it asks for its mother’s milk.

In the end, we read these to lines:

He is watchful while they are in peace,

For they know when their Shepherd is nigh.

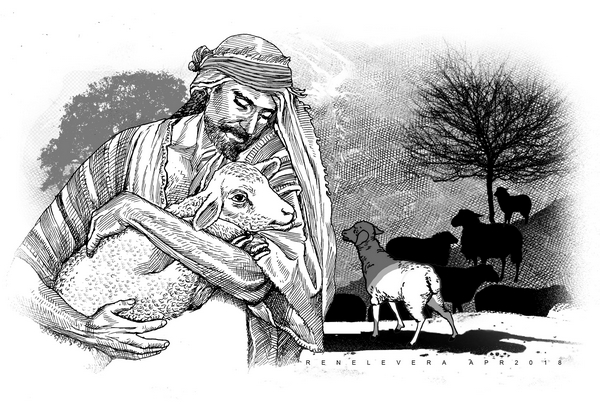

That Shepherd, with the capital S, is no doubt the Christ, the Good Shepherd, who watches over his flock, the church.

We find a description of the Good Shepherd in the Gospel of John.

“I am the good shepherd. A good shepherd lays down his life for the sheep. A hired man, who is not a shepherd and whose sheep are not his own, sees a wolf coming and leaves the sheep and runs away, and the wolf catches and scatters them. This is because he works for pay and has no concern for the sheep. I am the good shepherd, and I know mine and mine know me, just as the Father knows me and I know the Father; and I will lay down my life for the sheep. I have other sheep that do not belong to this fold. These also I must lead, and they will hear my voice, and there will be one flock, one shepherd.”

The shepherd that Jesus claims to be is not lily-livered, he is no weakling. He defends the sheep from the wolf even if this means losing his life. In addition, he seeks out other sheep to gather them into his fold, so that in the end all the sheep will be united under one shepherd, and listen only to his voice.

It may not be fair to measure Blake’s shepherd against the Good Shepherd. In simple, lyrical words — no doubt a reaction to the sophisticated rationalism of Alexander Pope and company — Blake describes a setting that is the opposite of the physically and morally shabby and disarrayed city that grew out of the Industrial Revolution. It is a clean, innocent world without conflict, in which sheep and shepherd are sufficient unto themselves and stand in no danger of injury or death. There is in it an air of tenderness, such as that between mother and child, between lamb and ewe. In effect, Blake is presenting a world in the time after time, eternity, heaven itself, in which the sheep are the souls that the Christ their shepherd has saved with his life.