Caedmon is the first English poet that we know by name. He lived in the seventh century and worked in a monastery as caretaker of animals. He could not read or write, and because he did not know how to sing and knew no songs, he did not join the monks in their gatherings, which were filled with music and merriment, and just stayed in the barn with the animals. One night, in a dream, someone approached and asked him to sing “the beginning of created things.” At first he refused, but later obliged and came up with a poem in praise of God, the Creator.

When he woke up, Caedmon remembered every word of the poem and he even added more lines to it. When the abbess of the monastery learned about it, she believed that Caedmon had received a gift from God, and commissioned him to write some more poems. As a result, Caedmon produced the most beautiful pieces about the spiritual life.

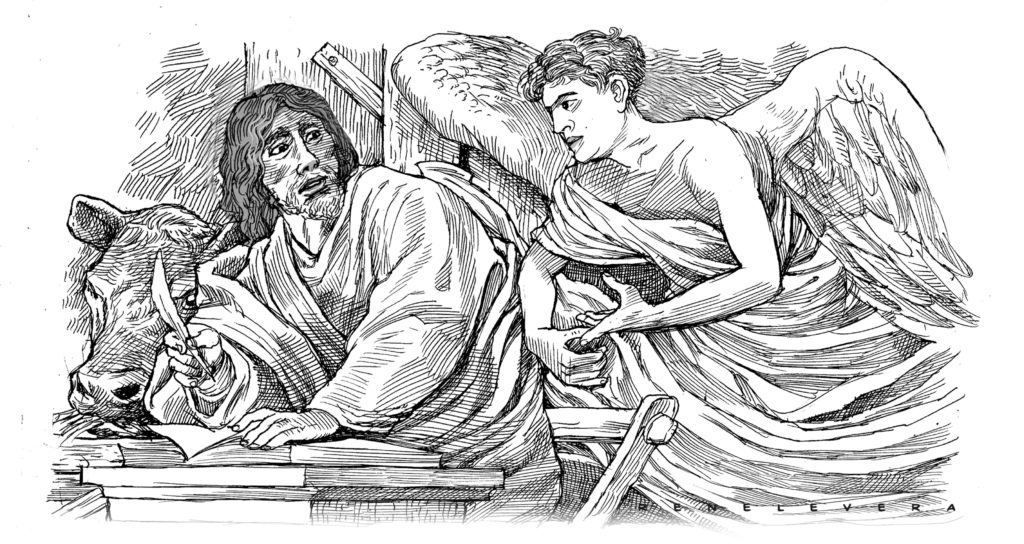

Denise Levertov wrote a poem about Caedmon, the last lines of which depict his sudden meeting with an angel which brought about his reception of the gift of poetry.

Until

the sudden angel affrighted me — light effacing

my feeble brain,

a forest of torches, feathers of flames, sparks upflying:

but the cows as before

sere calm, and nothing was burning,

nothing but I, as that hand of fire

touched my lips and scorched my tongue

and pulled my voice

into the ring of the dance.

The scene portrayed by Levertov evokes Pentecost, when the Holy Spirit in the form of tongues of fire descended on the apostles and the Blessed Virgin Mary. The apostles were transformed, these ordinary people, who were possibly unlettered, most of them being fishermen, and, because of what happened to their leader, Jesus, were deathly afraid of the Jews. They became a courageous lot, and came out of the room where they were hiding to preach the message of Christ. They were willing to suffer and even to die for it.

Caedmon’s encounter with the angel was his personal Pentecost. Before that, he could only admire the monks who spoke well (“All others talked as if / talk were a dance”), and would not enter the hall where the monks were celebrating, and would just stay near the door:

Early I learned to

hunch myself

close by the door

then when the talk began

I’d wipe my

mouth and wend

unnoticed back to the barn

to be with the warm beasts,

dumb among body sounds

of the simple ones.

There, among the cows, he would find himself at home, but was lonely. And then the angel appeared and changed him into a first-class poet.

The poem’s richness in biblical allusions is amazing. One writer pointed to the fact that Caedmon lived with animals, evoking the prodigal son in the parable who when his inheritance had run out worked among pigs. But, of course, Levertov could hardly have intended Caedmon, who despite his crudeness was basically a good man, to represent those who stray away from God and his people.

The writer likewise pointed to Caedmon’s humble origins, in which he resembled the shepherd boy David, the simple girl Mary, and the fisherman Peter, all of whom God called to do consequential tasks.

When Caedmon mentions the hand of fire that touched his lips and scorched his tongue, we remember Isaiah whose mouth a seraphim touched with a burning coal.

The poem speaks of how God regards our humbleness and how He takes the initiative to lift us up. Mary, the mother of Jesus, sums it all up in her Magnificat — “My soul magnifies the Lord and my spirit rejoices in God my Savior, for he has regarded the low estate of his handmaiden.”

Some commentators describe the relationship between the three persons of the Blessed Trinity — the Father, the Son and Holy Spirit — as a dance, a dance of love. At Pentecost, the Holy Spirit untied the tongues of the apostles and detached the knots in their minds and hearts so they could boldly and joyfully proclaim Christ. In Caedmon’s own Pentecocst, the Holy Spirit pulled his voice, timid for so long and as dumb as the voice of the cows he was tending, into the ring of the dance — the dance of God.