In Rome, on a ceiling in the Catacomb of Marcellinus and Peter, one finds a fresco that depicts the healing of a woman who had suffered from a protracted hemorrhage, an incident which we read about in the Gospels.

In his account, Mark writes that Jairus, a synagogue official, had pleaded with Jesus to lay his hands on his dying daughter. Accordingly, and with a large crowd at hisheels, Jesus made his way to Jairus’ house.

A woman, who had been bleeding for 12 years and not had any relief from, and only got worse in the hands of, the many doctors she had seen, came from behind and touched Jesus’ cloak. She had heard about him and knew in her heart that she would be healed if only she could do this. True enough, when she touched his clothes, the hemorrhage stopped at once and she felt healed.

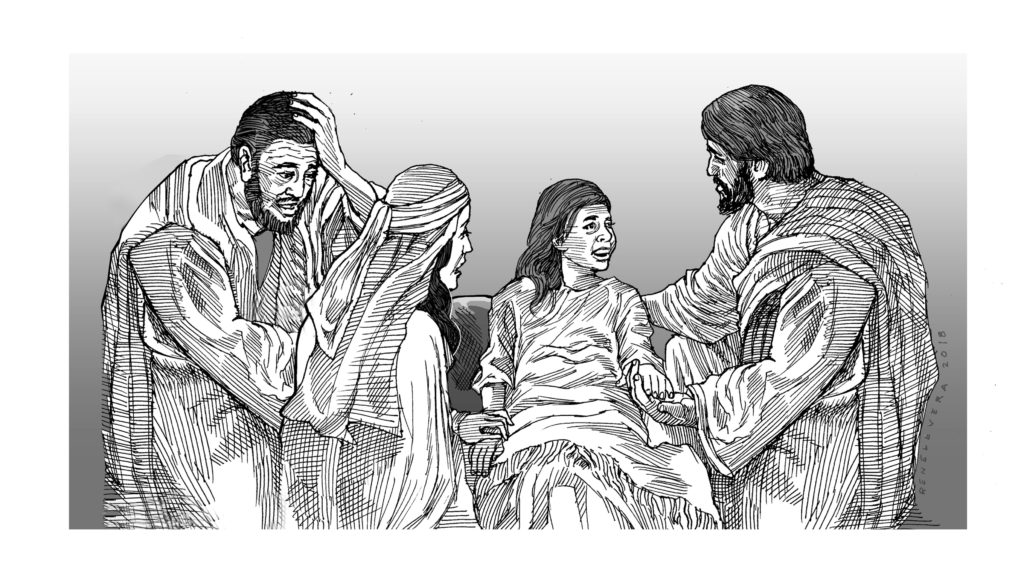

But Jesus felt that power had gone out of him, and so he turned around and asked, “Who has touched my clothes?” Out of fear, the woman fell down before him and admitted what she had done. Moved by this, Jesus told her, “Daughter, your faith has saved you. Go in peace and be cured of your affliction.”

One takes note of the simplicity of the fresco. Despite this, one finds a truthfulness, not just in the proportion of the human form but also in the fear in the woman’s eyes and Jesus’ look of concern. (The Lord comes across as lean and long-faced, his hair parted in the middle, the way that the catacomb artists usually portrayed him.)

The fresco gives us a peek at early Christian art, which largely grew in the catacombs, burial places underneath the city of Rome. While the Romans preferred to cremate their dead, the Christians, who believed in the resurrection of the body, would rather bury their dead, and the catacombs offered them space for this, since, being of the lower classes, the Christians had almost no access to regular burial grounds within the city.

The early Christians must have found a more than usual significance in the story of the bleeding woman. The art in the catacombs tended to portray symbols (fish, peacock, grapevine) and, when it leaned towards figure painting, essayed such popular themes as the Good Shepherd and the Resurrection, limiting itself, perhaps for reasons of space and resources, to just a few figures, usually not more than four.

But why, we might ask, portray an incident having to do with healing in the place of the dead? Definitely, the Resurrection, and even the Good Shepherd, might have more bearing. The obvious explanation lies in the fact that the artists addressed the frescoes to the living, those still on their spiritual journey, including the artists themselves.

And, which all of us still with breath should keep in mind, Jesus’ question—“Who has touched my clothes”—can only mean that the Lord responds to every desire and effort to reach out to him.