Among the better known works of the 16th-century Venetian artist Jacopo Tintoretto we should include an oil painting, “The Miracle of the Loaves and Fishes,” which now hangs in the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City. The piece presents a scene described by John in his Gospel. Jesus had crossed the Sea of Galilee followed by a large crowd which had seen him heal the sick. There he went up a mountain with his disciples. From where he sat, he could see the multitude approaching and asked Philip, “Where can we buy enough food for them to eat?” Philip answered, “Two hundred days’ wages worth of food would not be enough for each of them to have a little bit.”

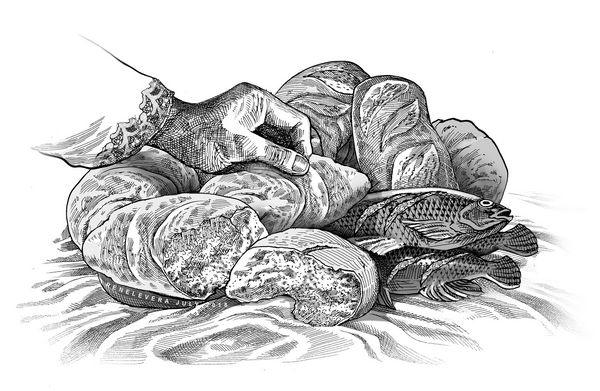

Another disciple, Andrew, the brother of Simon Peter, butted in, “There is a boy here who has five barley loaves and two fish; but what good are these for so many?”

Nonetheless, Jesus had the people, reaching about five thousand, recline on the grass. Then he took the loaves and the fish, gave thanks, and distributed them to those who were reclining.

Everyone had more than he could eat. Jesus had the disciples gather the fragments which filled twelve wicker baskets. Thereupon the people wanted to make Jesus king, but he withdrew to the mountain alone.

The painting displays the skills of Tintoretto, who regarded his art as “Michelangelo’s drawing and Titian’s color,” the inscription he placed above his studio. (He admired both artists but was not friends with Titian, under whom he studied, but who after just a few days dismissed him out of envy.)

In this painting, Tintoretto shows Jesus taking the bread and fish from the basket of a young boy and handing the food to Andrew for distribution. The men sit separately from the women, some of whom are with children, one nursing an infant and another escorting a cripple towards Christ. In the background we see a vast multitude rendered in grey, a method of painting called grisaille.

We would expect the crowd that Jesus fed to be humble people, but Tintoretto portrays them as a well-dressed throng, the women with jewels on their hair, the babies looking like cherubs. In effect, Tintoretto has turned the feeding event into an elegant party.

We can excuse Tintoretto for this license because he belonged to the Mannerist school, in which the artist portrayed the world theatrically rather than realistically.

But does not the feeding of the multitude presage the Eucharist, in which Christ, in the form of bread and wine, gives his body and blood to the faithful as food, the true food, as he put it? The Eucharist is, of course, an advance participation in that eschatological event that Revelation speaks about, the marriage supper of the Lamb, whose bride is the New Jerusalem.

Perhaps, in his painting, Tintoretto looks forward to that nuptial banquet in elegantly garbing the crowd partaking of the barley loaves and fish.

Had the artist clothed the people in white robes he would have belabored the obvious. Enough to clad them with the finery of the Venice of his day. Enough to suggest,

however liminally, that we should always be dressed and prepared for the coming of the bridegroom, Jesus the Christ.