In their first days at university, students of journalism or mass communication learn that in professional media, they have a four-fold mission — to provide audiences with information, education, entertainment, and means to exercise vigilance over the government.

With proper technical training and experience as well as ethical formation, the member of the press has little difficulty gaining proficiency at collecting, evaluating, editing, and disseminating information in ways that teach and when so required, entertain.

But far more than a learned disposition and a steady hand are needed by the journalist as a watchdog of the powerful, more so today when power wielders along with other threats prowl about seeking media to devour.

President Rodrigo Duterte’s regime seems to be marching in step with increasingly authoritarian, populist counterparts from Istanbul to Moscow to Washington.

In fact, however, his regime’s creeping suppression of press freedom is homegrown, inherited from the dark, generation-old Philippine martial law era under Ferdinand Marcos that began with Proclamation No. 1081 dated Sept. 21, 1972.

Back then, critical journalists were rounded and locked up or tortured to death.

Today, the Presidential Task Force on Media Security notwithstanding, they are deprived of the opportunity to witness (Rappler reporters barred from covering Duterte events); killed or subjected to harassment (at least 9 journalist killings, 16 libel cases, 20 cases of harassment on and offline), and accused of concocting fake news (Secretary Christopher Lawrence Go cries “fake news” as Philippine Center for Investigative Journalism reports on public works contracts awarded to firms owned by his relatives).

Back then, adversarial news organizations were shuttered while only sycophantic crony outfits were allowed to flourish.

Today, media companies critical of the government are threatened with closure or revocation of license to operate while the people behind fake news in the internet are emboldened by administration officials and high-profile supporters who are remorseless in their cavalier treatment of information. (Note the conflicting word of Defense Secretary Delfin Lorenzana and Presidential Spokesperson Herminio Roque Jr. on whether there is a military plot to oust the President — somebody is lying).

Back then, journalists and news organizations perceived to be under pressure to work or do business were granted relief on the condition that government censors under a so-called Media Advisory Council regularly sat beside their editors to decide which stories would see the light of day while military men and government lawyers ensured that the press toed the dictatorial line.

Today, scribes and their professional homes, like persons randomly named in barangay drug watch lists, are painted as destabilizers, with Ellen Tordesillas, Maria Ressa, and Eduardo Lingao as well as ABS-CBN, Philippine Daily Inquirer and Rappler making it to a purportedly secret short list of entities involved in an “Oust Duterte Movement.”

Tactics to weaken Philippine media are so unoriginal, their intended effects are so predictable: vilification of the journalistic establishment, citizen cynicism with journalists’ efforts to keep public servants honest, accountable, and transparent, and eventually the surrender of a nation’s liberties and destiny to the unchecked control of a tyrannical oligarchy.

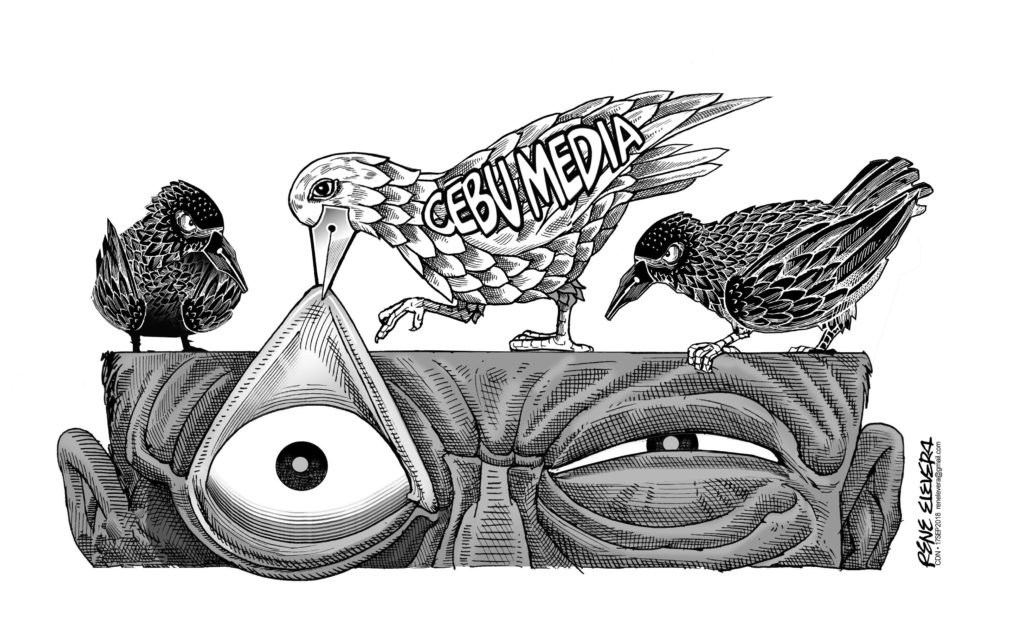

The media in Cebu stand united for freedom in this era of impunity, especially with reporters getting threats from state agents.

Beyond coalescing to withstand and surmount economic and technological pressures being brought to bear on our print divisions and beyond healthy professional competition, we are one in resisting and condemning attacks on press freedom.

As we celebrate Press Freedom Week, we invite our audiences–on whose behalf we exercise the constitutionally grounded freedom of the press — to stand with us.

Help us protect the space we need to realize our loftiest professional ideals.

This means more than criticizing media practice and appealing to its mechanisms for self-correction.

This means appreciating anew the centrality of press freedom to good citizenship and governance.

This means remembering that to subject authorities to journalistic inquiry and critique is not to be short on the powerful but to respond to a demand of fairness to the governed.

This means understanding that to expose anomaly or chime abuse is not to be biased against the revered but to be biased for the voiceless, marginalized, oppressed, cheated, deceived, or murdered.

Join us from your schools, churches, businesses, barangays, non-government organizations, and homes — across political persuasions — in guarding an unfettered press, thereby guarding our democratic experiment.

There is no overstating the grim alternative: swords unsheathed, pens discarded in pools of blood, a national propaganda machinery to bend at least 100 million wills to a caudillo’s whims.