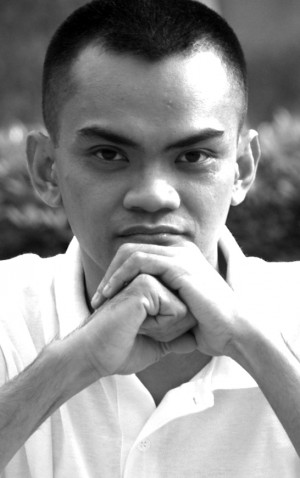

To those who have been following his column in CDN, Raymund Fernandez has been known for his oblique take on contemporary issues. Aside from art, which is his usual topic, being a professor at the University of the Philippines Cebu Fine Arts program and a practicing artist, he doesn’t hesitate to tackle topics we normally avoid at the dinner table: politics and religion.

Of relegion, he would make us rethink our assumptions about God and what it takes to be good. His inquiry and critique of the church can be unsettling. I recall once reading a priest’s response to his article. Not a few times have I myself debated publicly with Raymund during art gatherings.

Recently, however, I noticed that he has been increasingly making artworks that tackled religion, some of them even commissioned by the church. There was, for example, that Jesus statue he made for the Jesuits.

His latest work on religion is a group of installations he made with his artist wife Estela and their kids, particularly 14-year-old Linya who shows the strongest inclination to art. The works are commissioned by Cebu Holdings, Inc. for local reverence to Pope John Paul II, during his recent canonization.

Entitled “Movement and Spirit”, the public art exhibit is located among a group of trees next to the Avida showroom in the Cebu IT Park and may stay there for about three months. This collaborative work includes photographs on tarpaulin sliced into sails by Raul Arambulo, paintings of Pope John Paul II digitized on the tarp streamer, and, of course, the three art installations of the Fernandez family.

The first work consists of Linya’s graphite portrait of the Pope on a white geometric plywood panel designed by Estela. The portrait also has hands cast in resin and a walking stick made of copper topped by a cross that makes it resemble the Pope’s own iconic walking stick. Raymund, a metal sculptor who often use copper as material, designed this cross.

Another work is entitled “Upon This Rock” and consists of an old circular grinding stone suspended from a tree by hundreds of rubber band in different colors. As the title suggests, the work symbolizes how the church (the rock) has been supported by multitudes of individuals. According to Raymund, the millstone also suggests “how as individuals we are refined by the church”.

A striking image of a bamboo globe wrapped in clear packing taped and topped by a sail is the installation entitled “Kasingkasing” (Heart). The use of packing tape makes references to travel or diaspora more evident. And yet, the use of local bamboo for the globe called “Heart” suggests a sense of home, a kind of core that binds us in our separate journeys, spiritual or otherwise.

“I’ve always been religious but not the conservative religious,” Raymund says. “I’ve always done religious work. It’s not the sanctioned icons of the church. I’m not really into that.”

The artist feels that contemporary art that tackles religion is something that has not really been appreciated by the clergy who still hold on to conventional notions of religious art. He also thinks that, being in such a religious country, it is important for artists to reflect on religion and spirituality.

“I like religious discourse,” he says. “People should be talking about religion. I don’t mind doing work that touches on spirituality.”

Raymund’s journey back to his childhood faith is not totally surprising. A lot of artists, while remaining mostly secular or even aesthetic, have at one point (which is usually later in life), confronted religion or the question of the spiritual in their work.

The socialist architect Le Corbusier accepted a commission to build the Notre Dame du Haut church in France, one of the finest examples of modern church architecture even before modern art was officially allowed by the church in the wake of the Second Vatican Council.

One of the most controversial of the contemporary artists, Damien Hirst made a series of works on the gospels that include cows and lambs cut sharply into halves and preserved in a tank of formaldehyde. Hirst prefers to portray religious subjects in transgressive ways so as to make us rethink conventional iconography or representation of Biblical themes in art.

While remaining an atheist all his life, Ingmar Bergman made “The Seventh Seal”, a film that even the Vatican endorses for how it shows a longing for God and the fear of death.

Raymund admits that “an occasional fear of death and my mortality” also prompted him to think more and more about religion and spirituality and to express these thoughts in his art.

“I’ve worked with Linya lately. Di man gud mainstream ang iyang religiousity. They grew up watching “Jesus Christ Superstar”. We’ve always been more edgy in our approach for religious art.”

As in their work “Kasingkasing”, Raymund finds his way home, his heart, which is the core of his childhood faith. And I guess his own child Linya has helped led him to this homecoming.