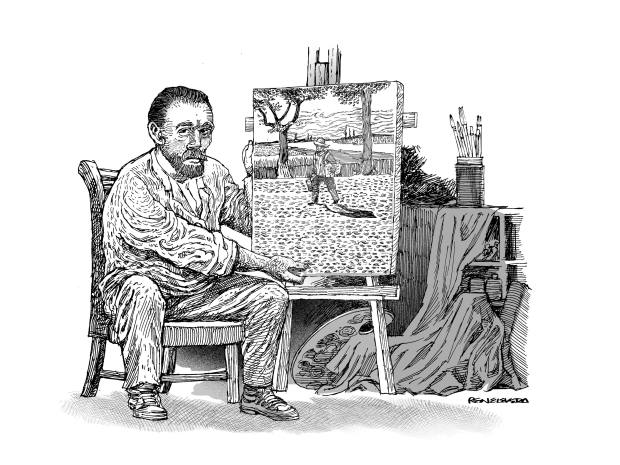

In the Second World War, Allied forces bombed Magdeburg, setting fire to the Kaiser-Friedrich Museum where the Nazis had kept the paintings they had seized for being “degenerate.” Together with the works of such as Marc Chagall, Henri Matisse and Pablo Picasso, Vincent Van Gogh’s “Painter on the Road to Tarascon” went up in smoke.

Van Gogh made the painting in 1888. He sent it to his brother, Theo, together with other studies, describing it as “a rough sketch I made of myself laden with boxes, props, and canvas on the sunny road to Tarascon.” Tarascon lies 20 kilometers north of Arles in Southern France, to which Vincent had moved in 1886.

The painting shows the artist trudging a lonely road on a day so bright that his hat, his box, the road and the fields, all of which claim the lion’s share of the canvas, blaze with eye-splitting yellows. The artist’s shadow, which because of the position of his walking stick appears like an animal on a leash, serves as counterpoint to, a break in, the blinding brightness.

I find in this Van Gogh’s statement about his life. He had searched for the way, and found it in art, and so every road became for him the true road if he could turn it into the road to Tarascon, where he could pursue his art, and with his brush transform the landscape into something other than what it was, into a kind of lie, in order to make it conform to a deeper truth.

Note the words – way, truth, life. Don’t we likewise find them in the Gospel of John? When Jesus told the disciples that he was leaving to prepare a place for them in his Father’s house, and that they knew the way to where he was going, Thomas responded, “Lord, we do not know where you are going, so how can we know the way?”

“I am the Way, the Truth and the Life,” Jesus said, “No one can come to the Father except through me.”

Ourselves, we search for things and places. In fact we look high and low for happiness, which, let’s stop pretending, is ultimately God. And we read in John’s Gospel that the way is Jesus himself, who, because he is the only route to the Father, is both road and destination.

Perhaps the truth that Van Gogh looked for lay along every virtual road to Tarascon. But, no matter how much it excited him, his art fell short of the life that was meant for him. In the end – poor, mentally ill and unknown – he shot himself.

In one of his letters to Theo, Vincent wrote, “I long so much to make beautiful things. But beautiful things require effort – and disappointment and perseverance.”

And he confessed in yet another letter, “I haven’t got it yet, but I’m hunting and fighting for it. I want something serious, something fresh – something with soul in it! Onward, onward.”

Well, Vincent both found it and did not find it. We know that he began by selling all he had and working as a Christian missionary with the coal miners in Belgium, but for some reason was rejected by his church, the Dutch Reformed Church, which cut off its support for him. This drove him into an artistic career – he began to make drawings of the humble lives of the Belgian peasants.

At one time, Vincent described Jesus as “the supreme artist, more of an artist than all others, disdaining marble and clay and color, working in the living flesh.”

Might not his masterpiece, “The Starry Night,” which he painted at St. Rémy’s Asylum at the end of his life, be his praise for the God of Creation, whom St. Augustine addressed as

“Beauty so old and so new,” without which no beautiful thing could ever exist.

He alone, who claims to be the Way, the Truth and the Life, is the Supreme Artist. And he alone, who can fill up all five of our senses, can be the Supreme Work of Art, whom St. Augustine eulogizes: “You called and cried out loud and shattered my deafness. You were radiant and resplendent, you put to flight my blindness. You were fragrant, and I drew my breath and now pant after you. I tasted you, and I feel but hunger and thirst for you. You touched me, and I am set on fire to attain the peace which is yours.”