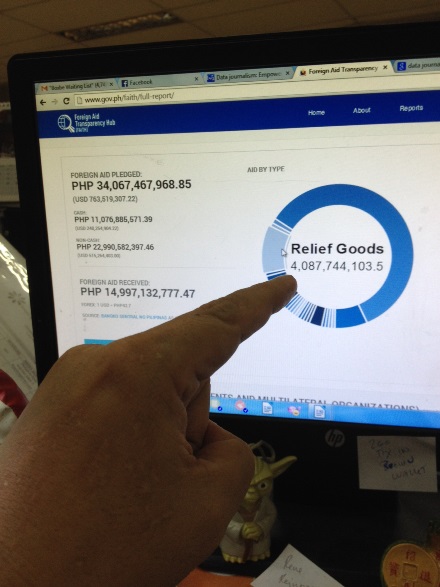

The FAiTH website posts data on Yolanda-related donations as part of the Aquino administration’s efforts toward transparency. The hub categorizes the donations into cash and noncash, both valued in pesos.

A total pledge of P34,067,467,968.85 from countries, institutions and individuals for the areas devastated by supertyphoon Yolanda (international name: Haiyan) last year, according to the Foreign Aid Transparency Hub (FAiTH). But beyond the huge amount there’s more that the public can look into.

FAiTH (www.gov.ph/faith) posts data on Yolanda-related donations as part of the Aquino administration’s efforts toward transparency. The hub categorizes the donations into cash and noncash, both valued in pesos.

A piece of information sticks out: The country has received only 44 percent (just under P15 billion) of the total amount pledged. The why is not readily answered by the infographics (www.gov.ph/faith/full-report).

Scroll down and you find a forum criticizing the available data. One user called FAiTH “partial transparency”, full only when the expenditures were shown. Another described it as a “fraud”, tracking only what came in and not what reached ground zero.

Two people suggested that the critics pore through the links, which could reveal some answers. The links automatically download the specifications in comma-separated values (readable by Microsoft Excel) or in JavaScript.

EXCITING

The interactions on the government-hosted website reflect the “exciting” data ecology that Open Knowledge Foundation (OKF) sees unfolding across the globe in a “momentum”, with governments, “closed for hundreds of years”, finally releasing data for public access.

“Information is power,” said Anders Pedersen, a member of OKF’s Knowledge Team, when he visited the Philippines for a data skills workshop. “When governments share information, that’s a sign that power is opening up. Governments used to keep information, keep power and now it’s been different.”

“It’s very exciting,” Pedersen added. “It means that the information that’s becoming available offers us a lot of new ways to cover society and to help citizens find out what’s happening, to hold the governments to account.”

He cited the Philippine Government Electronic Procurement System (philgeps.gov.ph) as a compelling example. It is a centralized database of the government’s bidding opportunities for goods, civil works and consultation services.

OPEN KNOWLEDGE, VISUALIZATION

Open data suggest that certain information should be accessible for public consumption. The data then becomes open knowledge when “useful, usable and used,” OKF (okfn.org) said, explaining the organization’s purpose.

Visualizations like the charts and tables available on FAiTH hope to make the data “useful” for netizens, turning them into attractive and comprehensible information compared with the spreadsheets they originated in.

The formats of the downloadable data make the information “usable” as they are machine-readable and reproducible by netizens.

The third criterion (“used”) is met when Filipinos know that FAiTH exists and actively look at the data sets, and identify loopholes, according to Pedersen.

“Demanding better data will help inform government about what they need to change,” he said. “As citizens and journalists, we need to tell them we’re using the data. We want the data and this is the next data set we would like them to release.”

Demanding better data comes with the times.

“Asking information from government used to be a physical transaction—bring the papers to someone, you send them the papers—and [the papers] were very complicated to analyze,” Pedersen said. The then-arduous efforts at data hunting can now be directed at doing better analysis and presentation.

Technology has come a long way. “Your smartphone has the data capacity of the Apollo [that landed in the moon],” Pedersen said, adding that 1 terabyte, 1 trillion bytes, is now worth less that $100, from $450,000 two decades ago.

Computers store data in bytes and if a minute of MP3 music is 1 megabyte, that’s about two years of music.

The Internet has also become a potent partner in open data. It hosts interesting infographics from how fast Los Angeles fire marshals respond to 911 calls (Los Angeles Times, “How fast is LAFD where you live?”) to which Tanzanian secondary schools have performed well or horribly in the period 2003-2013.

CROWDSOURCING

“We are able to do new things that we weren’t able to do before,” said Pedersen, also citing citizen journalism as a good example. It involves crowdsourcing or user-generated content, which encourages ordinary citizens to contribute to the data pool. With a smartphone, for example, one can snap photos of hazards on the road and forward it to media and, in some countries, to government.

WikiLeaks produce a steady stream of previously confidential data sets. In a novel feat, Norway’s Verdens Gang identified the people in a photo taken during an event of the royal family there, via posting the photo on the Web and letting people comment.

The Data Journalism Handbook (datajournalismhandbook.org) provides a wealth of examples. Apart from the definitions and basic how-to’s usually found in books for data-journalism tyros, it has behind-the-scenes details for some stellar examples of data-driven journalism.

GRANULAR DATA

In the United Kingdom, OKF would tell a regular worker earning £25,000 monthly that 44 cents of his daily tax goes to culture projects and 28 cents is allocated for the environment (wheredoesmymoneygo.org/dailybread.html). The project is based on OpenSpending, in which Pedersen is a community coordinator. The group tracks data on government spending and tax allocations.

“Granularity is king,” Pedersen said, suggesting that data sets gain impact when they are made more specific.

In 2010, WikiLeaks released “Iraq War Logs,” a compilation of more than 390,000 military reports documenting military operations in Iraq from 2004 to 2009. It showed that the biggest death toll (over 60 percent) was accounted for by civilians; “31 civilians dying every day during the six-year period,” WikiLeaks said. / by Ana Roa and Vaughn Alviar, Inquirer