Filipinos of a certain age make it a ceremony to remember Sept. 21, 1972, for the imposition of martial law, which the dictator Ferdinand Marcos formally announced two days later. Far from being a tedious chore, the yearly commemoration is an act of will to retrieve from the mists of memory a dark era of brutality and resistance; it is as well a pushback against the efforts of the dictator’s heirs and their enablers to distort the narrative according to their determined stab at respectability and recapture of power.

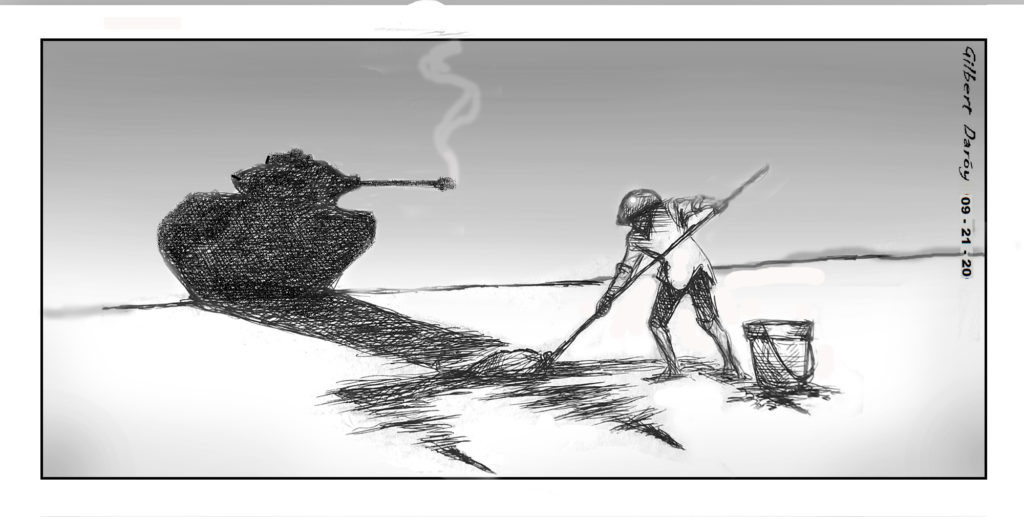

Certain young Filipinos also take part in this ritual, having embraced the imperative of learning from history in order to bring about a just and equitable society, indeed the necessity of standing firmly against authoritarianism, whether in its stark form in the Marcos era or in manifestations, nuanced but unmistakable, in the present day.

In remembering the imposition of martial law, Filipinos young and old are not flailing at a distant chapter in the national life from which, the Marcos heirs insist, the nation must “move on.” The matter is far from closed: The physical wounds may have acquired rudimentary scabs but they run deep and continue to afflict the body politic. The burial of Marcos’ remains at the cemetery for heroes, a stealthy operation aided and abetted by state forces, spits at the tens of thousands who were tortured, made to disappear, murdered, and otherwise savaged for resisting the dictatorship. The orphaned and desolate, bereft of closure, remain trapped in the net of mourning. The steady, moreover remorseless, inroads of the Marcos heirs back into the realm of power from which the family was wrested in February 1986 flesh out the dangers wrought by ignorance and the folly of forgetting.

Almost half a century later, Filipinos are still paying for the “debt-driven growth” that defenders of the dictatorship spin as a “golden age” — a phenomenon marked by heavy borrowing that, according to the economist Emmanuel de Dios, “produced historically impressive growth” but also “created the conditions for the big collapse later.”

The commemoration of the imposition of martial law thus includes an understanding of, in the formulation of the political scientist Teresa S. Encarnacion Tadem, the 3-legged stool that propped up the dictatorial regime: the military, Marcos’ relatives and cronies, and the technocrats.

This understanding results from a study of the facts and figures of Marcos’ martial rule, including the “loss of two decades of development” in which the GDP declined after 1982 and did not reach the same level until 21 years later, as well as the unemployment and underemployment that ultimately led to the wholesale export of Philippine labor. Overseas Filipino workers were still deployed in droves before the pandemic, their remittances a major pillar of the economy despite the breakup of families, the generations of parentless children, and the endangerment, even the brutal end, of lives in hostile cultures.

And the benefits supposedly to accrue from the Marcos-era levy imposed on poor coconut farmers, which allowed certain cronies to build and grow business empires, are still a pipe dream for these same farmers now old and dying, and their children.

Yet another aspect of martial law from which this nation cannot conceivably move on is the looting of the national coffers and the transfer of funds to accounts overseas. Official records are available for those who wish to be educated on the issue.

The money that Imelda Marcos spent in trips abroad as first lady and ranking official of the Philippine government remains a shocking display of excess even decades later. A glimpse is provided in the report of the Los Angeles Times’ Bob Drogin on the planned Sotheby’s auction in September 1981 of a $5-million collection of 17th- and 18th-century English paintings, furniture, and pottery from the New York apartment of philanthropist Leslie R. Samuel, which was abruptly cancelled because Imelda Marcos had “purchased the entire contents of the catalogue.”

Per Drogin’s account, Imelda Marcos’ visits to New York jewelers in May-June 1983 resulted in check disbursements made by Fe Roa Gimenez, then a secretary at the Philippine Consulate, in the amounts of: $100,000 as partial payment to Van Cleef & Arpels for “workmanship on emerald and diamond and ruby necklaces”; $200,000 to Fred Leighton Ltd. as partial payment for “antique jewelry”; $8,500 to La Vieille Russie for gold cuff links; $200,000 and $208,000 to Cartier Inc. for a diamond necklace and an emerald and diamond bracelet, respectively; $52,000 to Harry Winston for heart-shaped earrings…

Neither Imelda Marcos nor her lawyers were present when the Sandiganbayan convicted her of seven counts of graft on Nov. 9, 2018; she was seen partying on the night of the same day. She remains free on bail.

Filipinos grapple with these ironies in remembering how the dark night descended 48 years ago.