In fact the weeds can grow in places as high as the cornices of tall buildings, from seeds that the wind or the birds might have deposited there. (Children pass the time blowing the downy seeds of the dandelion off their stem, and, thus freed, the seeds ride on the wind for ledges high and low.)

A few months ago, the wife and I had a brainstorm to find ways of dealing with the bald spots around the small house at the back of our old one. One of us proposed filling them up with pebbles, the same that the river current makes round and smooth. But, granting their availability, we had no assurance of an adequate supply of these pebbles, bearing in mind the strict rules on the gathering of such materials, the environment having become an urgent global issue.

The recommendation came up that we should just fill up the bare areas with cement, but this failed to get any backing. It seemed too easy a way out. Besides, cement wastes the rain, shunts it from its natural destination, deep into the soil, the only, the heaven-decreed place for it, and conducts it towards the drainage canal that has no choice but to relay it to the sea.

What of flowers? I bragged that I knew of varieties that not only had the color of rubies, egg yolk or milk, but also had the tenacity of grass to carpet the ground, turning its green canvas into a Jackson Pollock painting. But when asked for details, I found myself checking old almanacs and asking old-timers, and finally flicking through a coffee table book on modern art.

In the end we settled for a variety of grass. It helped that the day before a man came to the neighborhood bringing samples of it. We contracted him to supply and install the grass, all of which he accomplished in two days.

When I read the parable in Matthew about the weeds that someone had sowed in the field among the wheat, I think of the grass in the garden. Because, after a while, weeds grew in the lawn, too, their jointed stems and long, narrow leaves bursting through the lines of the special, ornamental grass, to whose blades the weeks of tending already had given firmness and shape.

When told of the intrusion of weeds, the owner of the field in the parable declined the proposal of his servants that they go and pull out the unwanted plants. He would rather wait for the harvest in order to uproot, bundle and burn the weeds, and then to gather and store the wheat in his barn.

But in our case, we, rather irritably, instructed the help to kill the weeds upon sight, and make sure not to leave any part of the roots in the ground. (We forgot that the weeds could have come from the small, downy seeds of wind-pollinated flowers.)

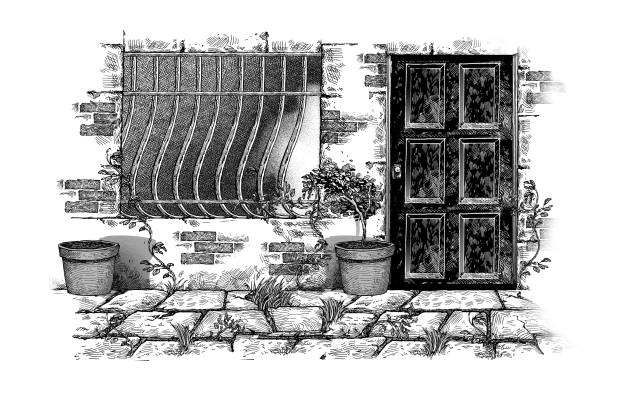

Clearly, the parable speaks of the patience of God. Both saints and sinners populate the land, but no one gets judged until the very end. Every one has the time and opportunity to, as it were, convert from weed to wheat (even as, in the case of the good seeds, the possibility to change from wheat to weed likewise remains). Who was it who said that, because of His decision to wait for man to come back to Him, God created time? Then time should have as icon, not the clock or hourglass, but God waiting outside the door. And perhaps in their silence the tiles and the grass of the patio in front of the door echo this call, this line from Revelations: “Listen! I stand at the door and knock; if any hear my voice and open the door, I will come into their house and eat with them, and they will eat with me.”