This week, we saw the highest health official in the nation wail about the Department of Health (DOH) being flagged by the Commission on Audit. For myself and my own colleagues in different corners of the health sector, to see not just a public official but a physician descend to such dramatics is upsetting. We are held to high standards in our own work every day, risking our health and our reputations for relatively little compensation, while Health Secretary Francisco Duque III complains when he and his office are also being held to high standards commensurate with his position.

In the first place, the idea that any public office should be exempt from audit and media scrutiny is absurd. Quis custodiet ipsos custodes? Clearly, if President Duterte had his way, no one would, and he and his ilk would have free rein over the country’s coffers as long as they hold office, government transparency be damned. But my focus now is on the health secretary, who must surely be familiar with the transparency and sense of responsibility that is expected of physicians.

Most of us in practice today are familiar with the concept of the captain of the ship; that is, the doctrine that physicians are in charge of the entirety of care of their patients, and that they are to be held accountable for all events within the scope of their supervision. This is a concept I have written about before, as such expectations of accountability are parallel to those for public servants (“Assuming responsibility,” 9/28/20).

While the doctrine of the captain of the ship is no longer held absolute, the concept remains: physicians deal daily with high stakes, and as such must be accountable for errors or oversights on all levels of care. Hospital departments have confidential audits, during which management of patients is reviewed and morbidities and mortalities are accounted for. Surgeons discuss their own missteps and critique their own techniques. Such audits are opportunities for improvement and part of a culture oriented toward good patient care. Such activities foster attitudes that help in anticipating, preventing, and managing issues and unforeseen events. It is only right that the care of patients is so discussed: patients are vulnerable and place their lives and resources in the hands of their physicians, and some degree of rigor, humility, and accountability is warranted. Often there is one primary physician who coordinates the health team, and who faces the patient and their family most often. We are thus accountable to our own colleagues and to our patients and their families, not to mention legally liable for lapses in care.

Such parallels should easily be comprehended by the health secretary. Accountability is at the core of what it means to be a physician, and this accountability exists, too, for the highest health official in the nation. I know of no physician who would point fingers or resort to dramatics when one of their cases is discussed at a conference. Why does Mr. Duque think he can do so when he is called to account? He isn’t even asked to account for every bad or belated decision the DOH has made as part of the pandemic response—just public resources. Doctors everywhere are compelled by their own professionalism to stand in front of their departments and say, “This is what happened to our patient. This is what went wrong, and these are steps we can take to avoid it happening again.”

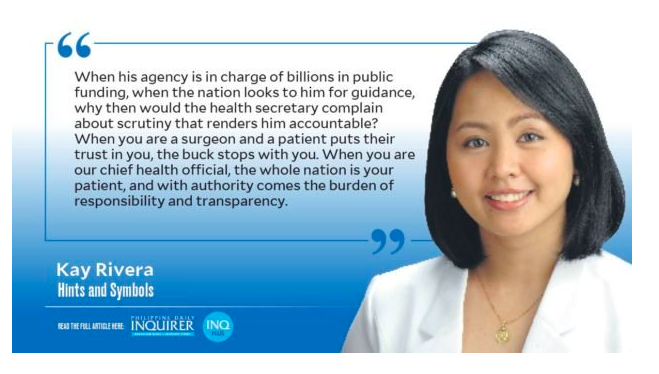

When his agency is in charge of billions in public funding, when the nation looks to him for guidance, why then would the health secretary complain about the scrutiny that renders him accountable? When you are a surgeon and a patient puts their trust in you, the buck stops with you. When you are our chief health official, the whole nation is your patient, and with authority comes the burden of responsibility and transparency. Mr. Duque should take a cue from junior surgeons everywhere who are learning the mantra, “I am sorry; I take full responsibility; I will do better.”

Moreover, it bears saying that the public is able to recognize the effort and drudgery of those hidden faces working under the DOH or its programs, who are unlikely to be the ones to benefit from large-scale corruption. Thus, contrary to the secretary’s claims, “winarak niyo ang mga kasama ko dito,” this is not the case. Such a remark to elicit sympathy on behalf of other DOH workers is both unnecessary and transparent.

On a final note, when a surgeon is incapable of delivering the standard of care—if he’s tired, intoxicated, incompetent, or sleep-deprived—then he owes it to his patient to step away from the field or the case. Except in the most acute of emergencies, he must refer the patient to a colleague of similar or greater experience or competency. The good secretary would do well to remember this, too.