The ceremony of remembering the dead is in full flower even as the living continue to be restricted by the pandemic. On television reportage on the rise and fall of the costs of cut flowers deemed needed for the ceremony bordered on the trite, as did footage of the pedestrian flow — children and elderly invisible — performing the obligatory visit to cemeteries before the gates were closed down. (Life is now bound by don’t-go-there and don’t-do-that, according to the diktat of task forces.)

Still there’s so much to remember in this sad season made bleaker under the aegis of state powers, so many stories to tell and recall of stilled lives: kin killed in the war on drugs or friends felled by the coronavirus, their numbers unprecedented. In these parts the plague is a beast with two heads. Or, actually, three: The vigorous crackdown on activists and other dissenters—marked by nighttime raids, “Bloody Sundays” and such—has orphaned many families, too.

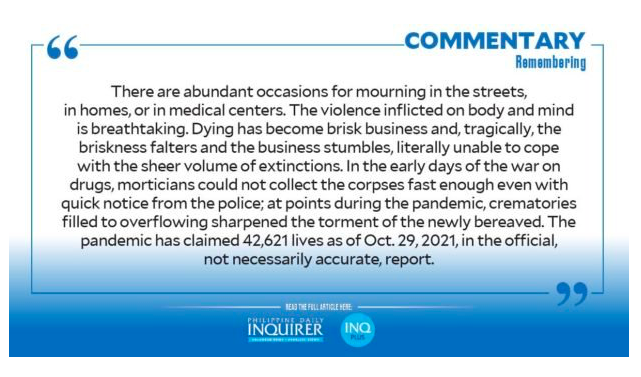

There are abundant occasions for mourning in the streets, in homes, or in medical centers. The violence inflicted on body and mind is breathtaking. Dying has become brisk business and, tragically, the briskness falters and the business stumbles, literally unable to cope with the sheer volume of extinctions. In the early days of the war on drugs, morticians could not collect the corpses fast enough even with quick notice from the police; at points during the pandemic, crematories filled to overflowing sharpened the torment of the newly bereaved. The pandemic has claimed 42,621 lives as of Oct. 29, 2021, in the official, not necessarily accurate, report.

The Department of Justice’s (DOJ) review of 52 cases of drug-related killings — a drop in the lake of 6,000 cases acknowledged by the Philippine National Police and a wispy ripple in the ocean of 30,000 estimated by rights advocates — tore at thinly scabbed wounds. Though seemingly grudging, as if made under duress, the review served as reminder of the blood spilled and the shocking aftermath — impunity so vivid as to perhaps drive the survivors to despair (or perhaps to resistance, whether overt or veiled).

And, to the sorrow of those who loved them, how young some of the dead were. The details overwhelm those who take note and do not forget (like the baby River Nasino who breathed her last away from her imprisoned mother’s arms). It is not in the ways of the world (if there is justice in this world) for the young to die when life is just beginning and brimming with possibilities.

The two junior cops who killed Carl Arnaiz on Aug. 18, 2017, in Caloocan City couldn’t be bothered by his youth. Per the DOJ review, they killed Carl, 19, “execution-style” after accusing him of carrying drugs and robbing a taxi driver — shooting him five times in the chest, as narrated by the same cabbie and another eyewitness. “The fact on intentional killing was confirmed by the physical evidence and the findings of the medico-legal officers from the Public Attorney’s Office,” the DOJ said, adding delicately: “The police operatives were found to have employed excessive force and violence.”

Yet Carl had just gone out with his friend Reynaldo “Kulot” de Guzman, 14, for a midnight snack back where they lived in Cainta, Rizal, according to those who loved them. In the gripping story told by news reports, Kulot himself disappeared after Carl’s killing, and his corpse was not found until weeks later in a creek in Gapan, Nueva Ecija. How far he had traveled.

The body bore 31 stab wounds, the head was wrapped in plastic and packing tape. Remember.

* * *

Grief remains profoundly personal despite the collective desolation triggered by the brutal passage of others. One ventures to examine it though one wonders at the wisdom of the science of tracking its stage, in a supposed effort, ultimately absurd, to come to grips with it.

Remembering is a constant ceremony occurring at unguarded moments: hearing the faint strains of a song, coming upon his still-ticking wristwatch—even observing oneself tripping on a box in a supermarket aisle and falling to the floor in slo-mo, hands instinctively thrust forward to break the impact (left hand dropping the bottle of Spanish sardines that he liked with his toast).

One muddles on, incredulous at the lengths of endurance.

Yet, like Neruda, “I pace around hungry, sniffing the twilight,/ hunting for you, for your hot heart,/ like a puma in the barrens of Quitratue.”