Pinoy Big Brother (PBB) provided a welcome respite from election issues by focusing our attention on the sorry state of Philippine history in our K-to-12 curriculum. Housemates failed big time in a history quiz that viewers saw as common or stock knowledge. Poor kids were unfairly painted as being uncommon or out of stock in history: When they got Gregorio del Pilar’s nickname wrong as Gorio instead of Goyo; when they couldn’t tell Melchora Aquino from “Tandang Sora”; when they got the acronym of martyred priests: MAriano GOMes, JOse BURgos, and JAcinto ZAmora as “MaJoHa” instead of “GomBurZa.” K-to-12 graduates are different from older folks and live in a world where MaJoHa probably refers to MA-cDondald’s, JO-llibee, and Pizza HA-t.

Responding to the social media storm, PBB delivered housemates Dustine, Luke, Gabb, Maxine, and Tiff to the Ayala Museum where I gave them a quick tour of the dioramas. They are the same age as my students, their questions and comments both on and off-cam demonstrated they knew some Philippine history. Perhaps, we should stop using a quiz bee format to measure historical knowledge. They got 8/9 quiz questions correctly not because I am a good teacher, but they were immersed in the Ayala Museum where the visual aids were literally larger than life.

Philippine history as a separate subject is taught in Grade 4 or 5 of the current K-to-12 curriculum. A follow-up course to expand and deepen student knowledge of Philippine history that used to be in high school was abolished, its content allegedly “integrated” into other subject areas like English, math, and science. Knowing that K-to-12 graduates’ last encounter with history is seven to eight years prior to taking my college course on “Philippine History using Primary Sources,” I just presume zero knowledge and start from scratch. I don’t assess my students based on rote memorization since these boring dates, names, places, and events can easily be found on Google. Philippine history is not about random facts, but an engaging narrative that teaches students rather how to gather and use facts for chronology, causation, critical thinking, and reflection.

What is the point of knowing that the declaration of Philippine independence from Spain was made from a window (not the balcony added later) in Emilio Aguinaldo’s Kawit home on June 12, 1898? These facts should lead to further questions: Why did Spain leave? How did the US steal independence from the Filipinos and colonized the islands for 50 years? Perhaps the lesson of June 12 should be that declaration of independence is one thing and knowing what to do with that independence is another.

What is the point of knowing that the declaration of martial law on Sept. 21, 1971, is not the date of its actual implementation days later? This fact should lead to an understanding of martial law and its excesses. Existing infrastructure used to prove a “golden age” under Marcos reveals an underside of displaced, marginalized, and impoverished people; that one of Imelda’s fabled tiaras is equivalent to many unbuilt school buildings or the full treatment of scores of tuberculosis patients.

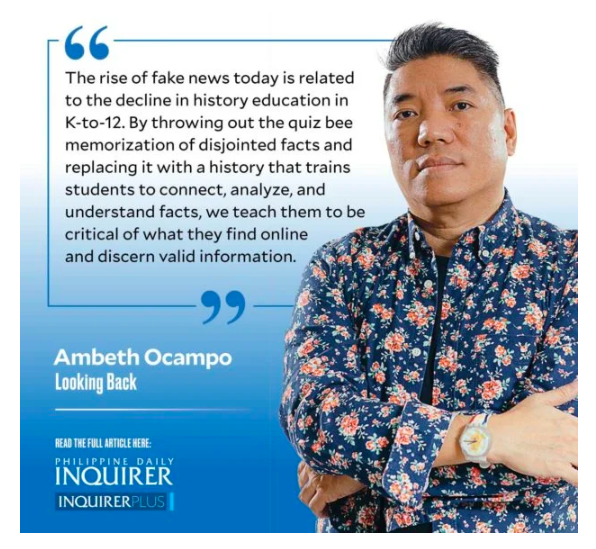

The rise of fake news today is related to the decline in history education in K-to-12. By throwing out the quiz bee memorization of disjointed facts and replacing it with a history that trains students to connect, analyze, and understand facts, we teach them to be critical of what they find online and discern valid information. Restoring Philippine History in high school is not a cure-all for this generation’s historical amnesia. Non-negotiables are: first, a standard Philippine history text that is factually correct, updated with current interpretations, and stimulates discussion; second, Araling Panlipunan and Kasaysayan must be taught by social studies or history majors; third, students are taught how to present their research, in written or oral form, by arguing a point and separating fact from opinion; fourth, that students learn to use the internet critically to recognize reliable sites and content from junk; fifth, students should learn to call things by their proper name, meaning that “historical revisionism” is wrong because revision entails review and correction; to do otherwise is “historical distortion.” Proper historical education will ensure that our present will stop reading like the past.

Comments are welcome at aocampo@ateneo.edu