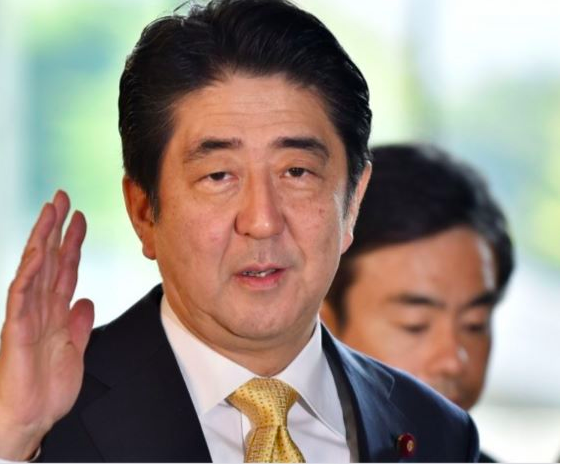

Former Japan Prime Minister Shinzo Abe. | Radyo Inquirer file photo

In 2014, I advised a thesis group that created an online archive for comfort women’s stories. They worked under the model of people’s history (as conceptualized by Howard Zinn), or history told through the eyes of those who experienced it, rather than those who glorify it for nationalist ends. The group (Denise Fernandez, now a writer; Alyssa Chuidian, now a brand strategist; and Justine Limjoco, now a lawyer) approached their work cautiously, but left with compassion and resolve.

They filmed their interviews with the comfort women and called their project “Voices: A Movement for the Lolas” (https://movementforthelolas.wordpress.com).

A concern that came up during their thesis defense was how they talked about their context. The students discussed their work, starting with the bombing of Pearl Harbor. Their panelist invited them to look closer: the war in our part of the world began much earlier when Japan swept through the Pacific as part of its campaign to “free” its neighbors from the West. This context would allow the students to understand the depth of women’s pain and our country’s wounds.

I remembered their project when former Japanese prime minister Shinzo Abe was assassinated last week. Abe was part of a political party that kicked out opponents, silenced critics, and lobbied for a nationalist agenda. Abe refused to apologize for Japan’s war atrocities, including comfort women.

Abe’s party also campaigned to amend Japan’s education law. In general, the new law mandates love for the country, but closer scrutiny reveals that the rules are pushing children to be more submissive to their government and less critical of the country’s past—all in a bid to promote a brand of patriotism that seems to focus on making Japan great and “beautiful” again.

No wonder Steve Bannon once said, of Abe, “He was Trump before Trump.”

Abe’s Japan stands in stark contrast to Germany: the rise of National Socialism and the Holocaust have been obligatory lessons in the German curriculum since 1992. Students as young as nine years old can learn about World War II and Germany’s role in it. This early education ideally should help students love their country deeply because they realize that without action on the part of those who are good, evil can prosper in the most insidious ways.

The critiques against Japan and its whitewashed history are no different from those thrown at the US and its approach to teaching race, and the UK and its approach to teaching colonialism. In both countries, teachers fear that children are too young to appreciate historical truths.

Research has shown, however, that children have more strength than we give them credit for: at age two, they start knowing right from wrong by experience; by age four, they can distinguish fact from fiction. Children, moreover, love stories of heroes who defeat evil.

It is this frame that can best tell the story of how humans construct their own realities, such as race or power; use these imagined concepts to create a hierarchy to control people, and then perpetuate these hierarchies over generations so that they persist in how governments deal with issues such as poverty and welfare. The heroes are those that fight these systems of institutionalized hatred and exclusion. The heroes are those who open the eyes of the blind, who awaken those who have lain asleep.

Reality is neither fair nor rosy, but difficult conversations need to be started, and attempts to shield children from reality should be questioned. It is not learned children that should be feared. It is the silence of society that reminisces about the nonexistent good old days while embracing lies.

We can applaud Abe for his policies, but we must not forget that he, too, leaves behind a society steeped in revisionist history. His end is a lesson in how truths cannot be hidden. It is a warning that resentments will always come to the surface, often in violent ways.

I return to that question posed years ago to my students, albeit in a different form today. How can we truly have a people’s history when we allow our truths to be glossed over with conspiracy theories and polluted by falsehoods?

We don’t have to look too far to see examples of how history is born, and how history is assassinated.

iponcedeleon@ateneo.edu