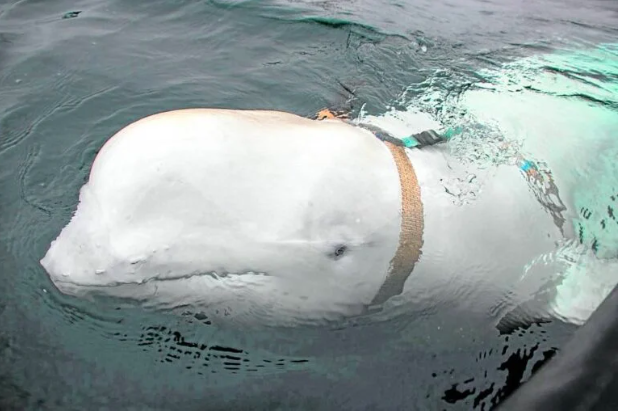

This file handout photo taken on April 26, 2019, released by the Norwegian Directorate of Fisheries (Sea Surveillance Service) shows a white whale wearing a harness, which was discovered by fishermen off the coast of northern Norway. The harness-wearing beluga whale that turned up in Norway in 2019, sparking speculation it was a spy trained by the Russian navy, has appeared off Sweden’s coast, an organization following him said on May 29, 2023. (Photo by JORGEN REE WIIG, Norwegian Directorate of Fisheries / Agence France-Presse)

STOCKHOLM — A harness-wearing beluga whale that turned up in Norway in 2019, sparking speculation it was a spy trained by the Russian Navy, has appeared off Sweden’s coast, an organization following him said on Monday.

First discovered in Norway’s far northern region of Finnmark, the whale spent more than three years slowly moving down the top half of the Norwegian coastline, before suddenly speeding up in recent months to cover the second half and on to Sweden.

On Sunday, he was observed in Hunnebostrand, off Sweden’s southwestern coast.

“We don’t know why he has sped up so fast right now,” especially since he is moving “very quickly away from his natural environment,” Sebastian Strand, a marine biologist with the OneWhale organization, told Agence France-Presse (AFP).

“It could be hormones driving him to find a mate. Or it could be loneliness as Belugas are a very social species—it could be that he’s searching for other Beluga whales.”

Harness with mount

Believed to be 13 to 14 years old, Strand said the whale is “at an age where his hormones are very high.”

The whale is not believed to have seen a single Beluga since arriving in Norway in April 2019.

Norwegians nicknamed it “Hvaldimir” — a pun on the word “whale” in Norwegian, hval, and a nod to its alleged association to Russia.

When he first appeared in Norway’s Arctic, marine biologists from the Norwegian Directorate of Fisheries removed an attached man-made harness.

The harness had a mount suited for an action camera and the words “Equipment St. Petersburg” printed on the plastic clasps.

Accustomed to humans

Directorate officials said Hvaldimir might have escaped an enclosure and might have been trained by the Russian navy as it appeared to be accustomed to humans.

Moscow never issued any official reaction to Norwegian speculation he could be a “Russian spy.”

The Barents Sea is a strategic geopolitical area where Western and Russian submarine movements are monitored.

It is also the gateway to the Northern Route that shortens maritime journeys between the Atlantic and Pacific oceans.

Strand said the whale’s health “seemed to be very good” in recent years, foraging wild fish under Norway’s salmon farms.

But his organization was concerned about Hvaldimir’s ability to find food in Sweden, and already observed some weight loss.

Beluga whales, which can reach a size of 6 meters (20 feet) and live up to between 40 and 60 years, generally inhabit the icy waters around Greenland, northern Norway, and Russia.