In 2012, the wife and I visited the Monastery of the Incarnation in Avila, which St. Teresa entered at age 20, and in which she lived for 30 years and wrote and had many of her mystical experiences.

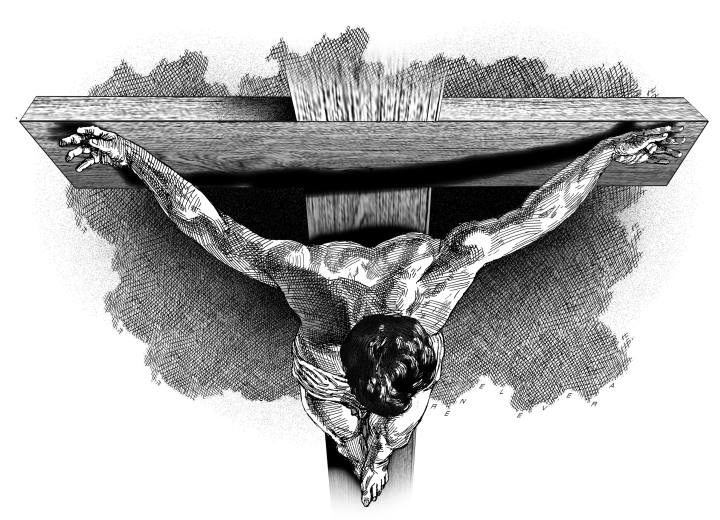

Likewise, St. John of the Cross, then in his early thirties, lived there, but only for a while. At one time, while praying in the convent, in a loft overlooking the sanctuary, he had a vision of the Crucified Christ. This he drew afterwards. The drawing became famous, not the least because of its perspective — Christ as seen from above – and inspired Salvador Dali in 1951 to paint a version of it, which he called, “Christ of Saint John of the Cross.”

Explaining his painting, Dali wrote:

“In the first place, in 1950, I had a ‘cosmic dream’ in which I saw this image in color and which in my dream represented the ‘nucleus of the atom.’ This nucleus later took on a metaphysical sense; I considered it ‘the very unity of the universe,’ the Christ!”

Dali’s painting depicts Jesus on the cross against a dark sky, floating above a lake with boats and fishermen. Dali claimed that his dream dictated that he present Christ without the blood and nails and the crown of thorns.

Since, as in the drawing of St. John of the Cross, the view is from above, Dali had a Hollywood stuntman pose while suspended from a gantry.

Many consider the painting too conventional for, and uncharacteristic of, Dali, who had gained fame as a surrealist painter. One critic even calls it kitsch and lurid, but nonetheless goes on to say that the painting is “for better or worse, probably the most enduring vision of the crucifixion painted in the 20th century.”

One cannot consider any more enduring vision of humankind than the image of the Crucified Christ. Any depiction of this somehow conveys the power and mystery of God’s love. In zeroing in on the Crucifixion, Dali chose to paint a subject already loaded with significance, and gave it a twist – inspired by St. John of the Cross – viewing the crucified Christ from a higher standpoint. And yet we sense a bit of theater in Dali’s work – the otherwise painful position of dangling from outstretched hands loses force from the absence of nails, as well as the healthy and athletic body of Jesus, which despite everything remains unstained by sweat or blood.

In contrast, the drawing of St. John of the Cross fits the description that Isaiah gives to the suffering servant – “so disfigured did he look that he seemed no longer human.” One notices how the drawing shows an over-thin and extremely emaciated Christ, and what large nails. Sometimes I wonder if Dali, an anarchist and a communist, whom George Orwell described as “a good draughtsman and a disgusting human being,” did not parody St. John of the Cross’ drawing with his own painting, to the point of claiming to have dreamt it too.

If Dali talked the talk, St. John of the Cross walked the talk. In his decision to follow Christ, the saint underwent imprisonment and torture and countless other sufferings, physical and spiritual. Upon these he based his writings, giving us the phrase, “dark night of the soul” – the title of a poem he wrote about the pain one undergoes in one’s journey towards union with God, enumerating for us the ten steps on the ladder of mystical love.

W. B. Yeats posed the dilemma that every artist faces – “The intellect of man is forced to choose / perfection of the life or of the work.” Dali opted for work, while St. John of the Cross decided to have both life and work, at once becoming a saint and an artist – one of the foremost poets of the Spanish language.