Chekhov reportedly said, “Don’t tell me the moon is shining; show me the glint of light on broken glass.” Many literary historians take this as the provenance of the “show, don’t tell” technique in writing, which prescribes that, rather than expounding, summarizing and describing, the writer should dramatically involve the reader in the story through action, words, thoughts and feelings.

But showing, which can take time, is best used to render dramatic moments. Telling can come in between scenes to speed up the story’s progress and prepare the reader for the important incidents.

A preeminent practitioner of this technique was Ernest Hemingway. Hemingway began as a journalist working as a reporter for The Kansas Star after high school. And when he lived in Paris, he served as foreign correspondent for the Toronto Star. His biographer, Jeffrey Meyers, wrote that Hemingway “objectively reported only the immediate events in order to achieve a concentration and intensity of focus—a spotlight rather than a stage”.

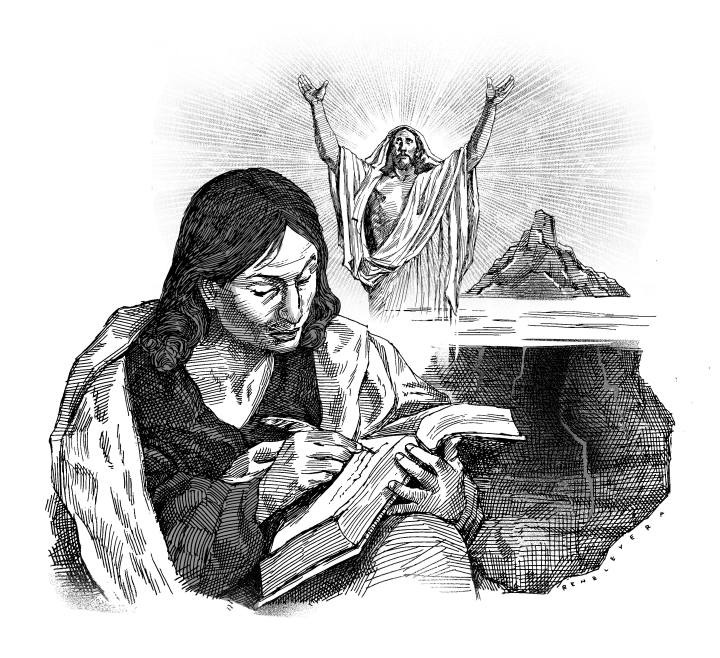

Hemingway would be happy with John’s account of the Resurrection. It is journalistic, has no personal interpretations and opinions. It follows the “show, don’t tell” technique to the letter.

“Early on the first day of the week, while it was still dark, Mary Magdalene went to the tomb and saw that the stone had been removed from the entrance. So she came running to Simon Peter and the other disciple, the one Jesus loved, and said, ‘They have taken the Lord out of the tomb, and we don’t know where they have put him!’ So Peter and the other disciple started for the tomb. Both were running, but the other disciple outran Peter and reached the tomb first. He bent over and looked in at the strips of linen lying there but did not go in.

Then Simon Peter came along behind him and went straight into the tomb. He saw the strips of linen lying there, as well as the cloth that had been wrapped around Jesus’ head. The cloth was still lying in its place, separate from the linen. Finally the other disciple, who had reached the tomb first, also went inside. He saw and believed. (They still did not understand from Scripture that Jesus had to rise from the dead.)”

Pure action is what we find in this account. Mary Magdalene finds the stone that covered the tomb moved away, runs to report this to Peter and John, who both race to the tomb to check, and find that indeed the tomb is empty except for the burial cloths.

When he wrote this account, John must have felt that he needed to present only the bare facts.

Here I am reminded of Hemingway’s Iceberg Theory.

Because of its density, only one-ninth of an iceberg appears above water. Hence, the expression “tip of the iceberg” to describe the manifestation of what is really just a small chunk of a much bigger problem or crisis.

In his book on bullfighting, Death in the Afternoon, Hemingway wrote:

“If a writer of prose knows enough of what he is writing about he may omit things that he knows and the reader, if the writer is writing truly enough, will have a feeling of those things as strongly as though the writer had stated them. The dignity of movement of an ice-berg is due to only one-eighth of it being above water.”

In other words, one need not include the things that those for whom one writes already know, or the “subtext,” the underlying or implicit meaning of the story.

When John wrote his Gospel, already the Resurrection was an accepted event, in fact the central event, among the early Christians, such that it was enough for him to narrate the bare facts without editorializing.

In his memoirs, Hemingway explained why he omitted the real ending in a piece of fiction — “This was omitted on my new theory that you could omit anything … and the omitted part would strengthen the story.”

What John omitted in his account, for the moment, because he wrote about the appearances of the Risen Christ too, heightened and intensified his bare bones report of the Resurrection. The prior showing validates the subsequent telling. And vice versa.