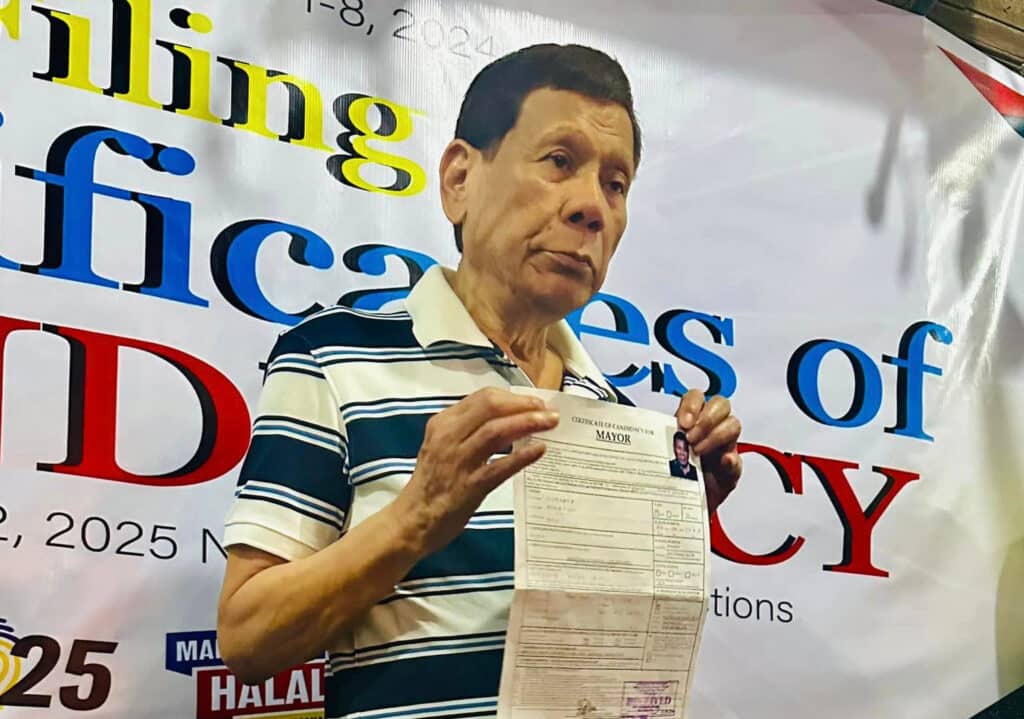

Former President Rodrigo Duterte files his certificate of candidacy for Davao City mayor on October 7, 2024. | PHOTO: Official Facebook page of Rodrigo Duterte

MANILA, Philippines — Former President Rodrigo Duterte’s past calls to kill drug suspects and “ninja cops” loom over his expected Senate appearance today, where he may face questions about the violent tactics of his drug war.

Senator Ronald “Bato” dela Rosa, Duterte’s former police chief, assured reporters on Saturday that his former boss would attend the Senate session.

READ: Pimentel tapped to lead Senate drug war probe

“He (Duterte) is ready. We did not talk about the investigation, but he said he will face the Senate and answer questions,” Dela Rosa said, adding that he recently had dinner with Duterte in Davao City.

But Senate Minority Leader Aquilino “Koko” Pimentel III, designated head of the drug war inquiry, said he had “no idea” if Duterte would attend today’s hearing.

“I did not find out whether his attendance was confirmed or not since we have a lot of invited resource persons and witnesses,” Pimentel told reporters also on Saturday.

“If he shows up, he (Duterte) can be a witness. If he doesn’t come, the hearing will still go on. Our hearing will not be held hostage by one person’s presence,” Pimentel said.

‘Follow the evidence’

The hearing is expected to focus on Duterte’s potential culpability in the thousands of deaths during his drug war, although Pimentel was noncommittal about any specific agenda to be followed by the inquiry.

“We will follow the evidence,” he said when asked if the Senate will revisit Duterte’s past “kill” rhetoric, in connection with the alleged reward system incentivizing the killings already raised before the inquiry of the House of Representatives.

Human rights lawyer and former party list congressman Neri Colmenares said he was cautious about the hearing, saying it could only be effective “if the senators will ask the genuine, important questions”—and if Dela Rosa and Duterte’s former Special Assistant and now Sen. Christopher “Bong” Go inhibit themselves.

Both are being eyed as possibly being among the most responsible for the over 7,000 deaths officially recorded during the drug war and even in the thousands others killed in Davao City when Duterte was mayor. Go, in particular, is being accused of facilitating the rewards system by testimonies before the House quad committee.

“This is where he (Duterte) might struggle to wriggle out of,” said Colmenares, legal counsel for the drug war victims who had filed charges of crimes against humanity against Duterte before the International Criminal Court (ICC). “Not only did he order the killings, but he also funded them. And not an ordinary person would spend millions of pesos just to fund such a thing… the only one with the capability to do that is the president.”

He was referring to the fact that the Office of the President under Duterte had requested billions in confidential funds.

Colmenares also expressed concern that should Duterte attend the hearing, it might be to “filibuster and meander, so that he could control the narrative.”

‘Uttered publicly’

A look back at Duterte’s statements and remarks revealed that he had promised millions of pesos to individuals who could bring “dead or alive” drug suspects or rogue cops.

These “encouraging words,” Colmenares said, was at the heart of their argument before the ICC, that his rhetoric effectively turned the killings into a “widespread and systematic attack” against civilians and proved he had “knowledge of the attack.”

For the most part of his administration, Duterte would either flip-flop or say he was merely exaggerating or joking.

But as the head of the executive branch, the police and all other agencies answer to him,” said University of the Philippines political scientist professor Maria Ela Atienza.

“He can say these are jokes or figures of speech, but these were uttered publicly. Whatever he said, these are to be taken [as] orders of the executive branch,” Atienza said.

As early as June 2016, Duterte already put a bounty of P3 million on drug lords or police involved in drugs, which he upped to P5 million later. Other bounties include P2 million for those overseeing drug distribution, P1 million for “second-echelon” syndicate members, and P50,000 for ordinary peddlers.

In Cebu, he raised the P5-million bounty to P5.5 million, describing it as a “premium.”

“I’m not saying that you kill them, but the order is ‘dead or alive,’” the former President said.

That same month, United Nations special rapporteurs already called out the bounties.

In September 2016, Duterte announced a P200,000 reward for police officers involved in successful operations against drugs and terrorism.

The next month, he announced to Zamboanga City police a P2-million reward for anyone who can give information on officers in illegal drugs and other criminal activities.

In August 2017, speaking in Ozamiz City, following the burial of slain Mayor Reynaldo Parojinog and three family members, he again offered P2 million to anyone who could help neutralize policemen in the narcotics trade.

“If you want money, go after them. No questions asked. I would not be asking who killed them,” he said.

Statements by Go, Dela Rosa

Go and Dela Rosa had even affirmed the President’s statements. In a 2016 interview, Dela Rosa said the reward was an “additional motivation” for police officers “instead of them receiving drug money.”

In 2019, Go confirmed the reward system, noting a P1-million bounty for dead “ninja cops” (rogue police officers allegedly in the drug trade) and P2 million if they resisted arrest.

Former Sen. Leila de Lima, who had also earlier testified before the House, will also appear at the Senate, her camp said. A showdown is therefore possible between Duterte and his leading critic in the drug war, if he shows up.

Atienza said the Senate inquiry, while it may be “unprecedented, …should not be surprising, because that’s the role of the legislature, and they’re making up for what they failed to do when the president was still sitting.”

“This is something like saving face, but better late than never,” she said.