Paolo Veronese joined Titian and Tintoretto to form the trio that ruled Venetian painting in the 16th-century. His works rest on narrative, portrayed with drama and color, and set in the majestic architecture of antiquity.

The oil painting, “The Raising of the Daughter of Jairus,” gives us a key to his style. A small painting, it has a height roughly double that of bond paper. Art historians consider it as one of Veronese’s earliest known works and perhaps his first narrative piece.

The work tackles the theme of faith, propounded in Mark’s account in his Gospel about a synagogue official, Jairus, whose daughter was at the point of death, and who pleaded on his knees for Jesus to lay his hands on her so that “she may get well and live.” Jairus took Jesus to his home, followed by a large crowd.

At this point, a woman, who had suffered from a hemorrhage for twelve years, came up behind Jesus and touched his cloak, believing that this would cure her. And indeed she experienced instant healing. Jesus felt that “power had gone out from him” and asked who it was that touched his clothes. Trembling with fear, the woman owned up to it and told him the truth. Jesus said to her, “Daughter, your faith has saved you. Go in peace and be cured of your affliction.”

Before Jesus reached Jairus’ house, news arrived that the girl had died. But Jesus said to him, “Do not be afraid; just have faith.”

When they arrived at the house, he said to the people who were wailing, “Why this commotion and weeping? The child is not dead but asleep.” And they ridiculed him.

Mark writes: “Then he put them all out. He took along the child’s father and mother and those who were with him and entered the room where the child was. He took the child by the hand and said to her, ‘Talitha koum,’ which means, ‘Little girl, I say to you, arise!’ The girl, a child of twelve, arose immediately and walked around. [At that] they were utterly astounded. He gave strict orders that no one should know this and said that she should be given something to eat.’”

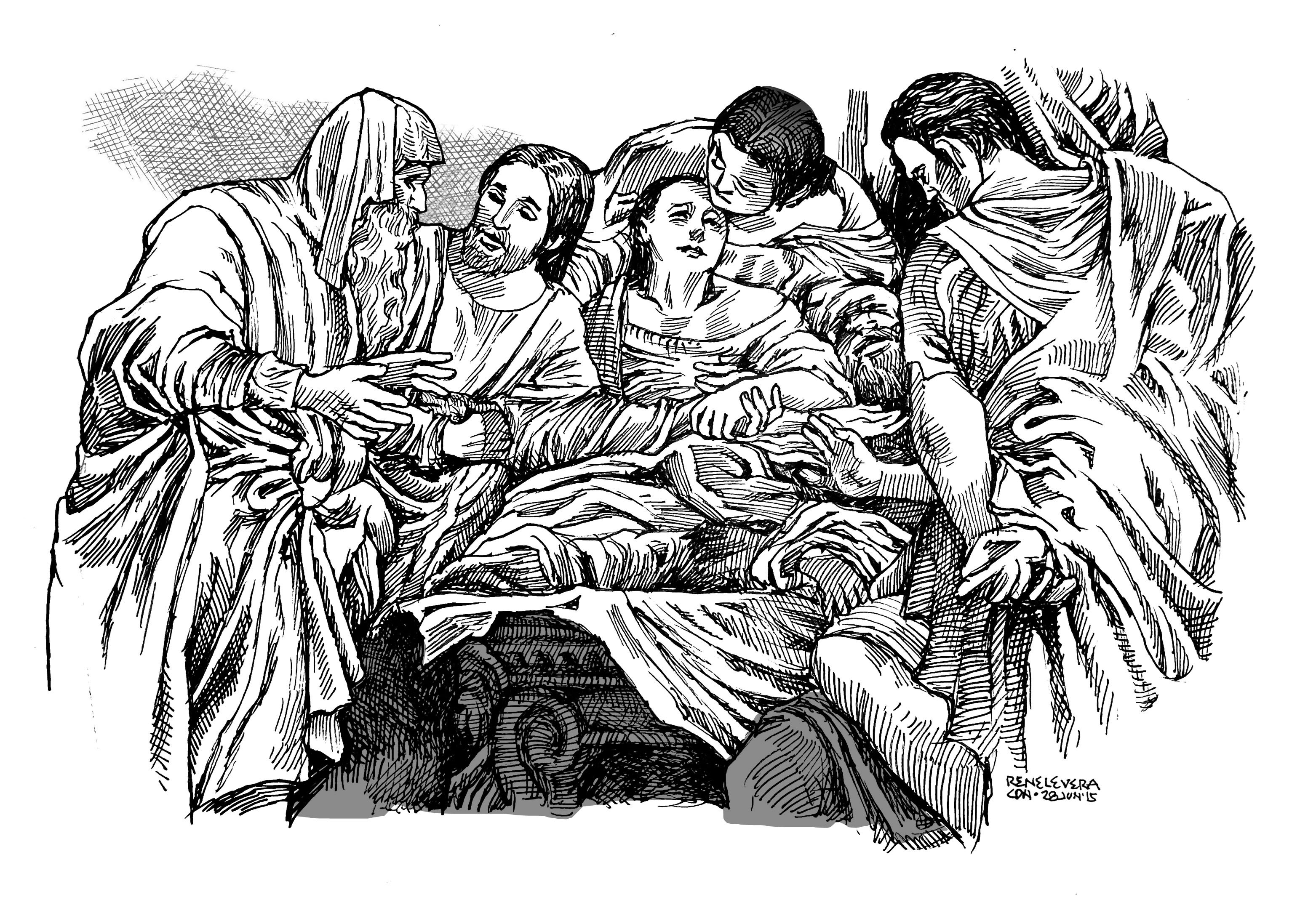

For his painting, Veronese chose the moment when the daughter was revived. He packed seven people into a small room – Jairus, Jesus, the girl, her mother, John, Peter, and a woman. The scene has an air of intimacy. It seems that the cramped conditions gave Veronese no choice except to make the movements dramatic. Hence, we see Jesus talking to Jairus while holding the girl’s hand; the mother tending to her daughter from behind; Peter almost leaning on the bed as he converses with John, who bends his leg; and a woman intently watching from above.

Veronese clothes the characters with exquisite fabrics, and yields to his fondness for Roman architecture. If the biblical account impels the painter faithfully to stick to the facts of the story, with which he acquiesces in the depiction of the event unfolding in the room, he demands freedom in the portrayal of the outside and extra spaces. As he once said, “[W]hen I have some space left over in the picture, I adorn it with figures of my own invention.”

Hence, we see a Roman arch outside and people going about their business, unconcerned, perhaps because they have no knowledge of or are unconcerned with what is going on inside.

Somehow, the disconnect between the exterior and the interior tells me something about the nature of faith and the manner of God’s visitation. Because, as St. Paul said, we walk by faith and not by sight, we see a different world in the one we perceive with our senses. Reality has two layers – the outside, with its Roman architecture and symbols of transient worldly power, and the inside, in which, concerned only with what lasts, we acknowledge the presence of the living God, who rescues us and lifts us up from weakness and defeat.