Metaphor lies at the heart of poetry. I once explained what metaphor meant to our daughter, then in high school. I started with simile, and gave as example – “Your lips are like roses” – which she understood quite easily. Then I took the matter one step higher and said – “Your lips are roses” – clarifying that the lips had not themselves become roses, but that it just happened that they and the roses had common characteristics, such as color and smell and overall attractiveness, which somehow allowed the identification of one with the other. Again she understood this. And then I asked her, “Supposing I say instead, ‘those roses,’ would you take it to mean ‘your lips’?” She nodded because she knew how the description had progressed. I added that ideally one must give clues in the poem to help the reader make the association.

Occasionally, we do not find the clues in a poem and consequently our understanding of it suffers. Or else we have to make several deductions before we get an inkling of what a poem means.

For instance, this line from the poem, “Outskirts,” by Tomas Tranströmer:

“The high cranes on the horizon want to take the great leap but the clocks don’t want to.”

I see the presence of high cranes, high because mounted on tall buildings, clearly still under construction. The speaker catches sight of the buildings and the cranes from a distance, since they loom on the horizon. The poem tells me that the high cranes “want to take the great leap.” We know that cranes cannot leap, and if they could what would “the great leap” mean? Mao Zedong used the phrase “the great leap forward” as catchword in the campaign to transform the Chinese countryside from an agrarian economy to a socialist society through rapid industrialization and collectivization. For the cranes to want to take the great leap might mean the desire of the operators of the crane, of the workers, for rapid progress to transform the outskirts into highly-developed areas. The phrase – “But the clocks don’t want to” – perhaps suggests that time – and all that it implies: the policies and the readiness of the government and similar factors – prevents this rapid progress from happening.

Tranströmer chooses not to make his meaning explicit, and to make the reader work it out by himself, which could deter him from fully enjoying the poem. Besides, whatever interpretation the reader gives can only amount to speculation.

Poetry hates the literal approach, the taking of the words at face value. Poetry uses metaphors because it proceeds by suggestions, by using Polonius’ advice to Reynaldo in Hamlet – “By indirections find directions out.”

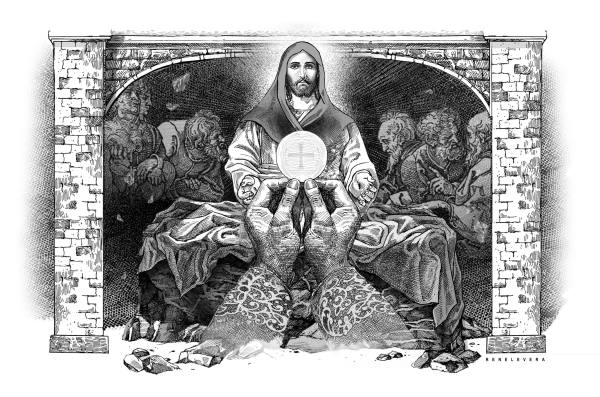

Incidentally, Jesus did not use symbolism when he said, “I am the living bread that came down from heaven; whoever eats this bread will live forever; and the bread that I will give is my flesh for the life of the world.”

The Jews took a literal interpretation of this and asked, “How can this man give us his flesh to eat?” But, instead of telling them that they should understand what he said figuratively, the approach that, for instance, his parables required, he insisted on a strict, plain, straightforward acceptance of his words – ““Amen, amen, I say to you, unless you eat the flesh of the Son of Man and drink his blood, you do not have life within you. Whoever eats my flesh and drinks my blood has eternal life, and I will raise him on the last day. For my flesh is true food, and my blood is true drink.”

This prompted many of the disciples to say – “This saying is hard; who can accept it?” – and abandon Jesus. Jesus turned to the Twelve and asked them, “Do you also want to leave?” And Peter said, speaking for all of them, “Master, to whom shall we go? You have the words of eternal life. We have come to believe and are convinced that you are the Holy One of God.”

It seems that the Jews had hoped that Jesus spoke only figuratively, using a metaphor, when he said – “The bread that I will give is my flesh” – and that what he really meant was – “The bread that I will give symbolizes my flesh.” When they realized that this was not so, they and many of the disciples were disgusted and turned away.

Thomas Aquinas writes in his poem, Pange Lingua Gloriosi:

The Word as Flesh makes true bread

into flesh by a word

and the wine becomes the Blood of Christ,

And if sense is deficient

to strengthen a sincere heart

Faith alone suffices.

Here the poem transcends metaphor and aspires to the condition of prayer. The words attain a reality that is as hard as fact. Poetry becomes incarnational.