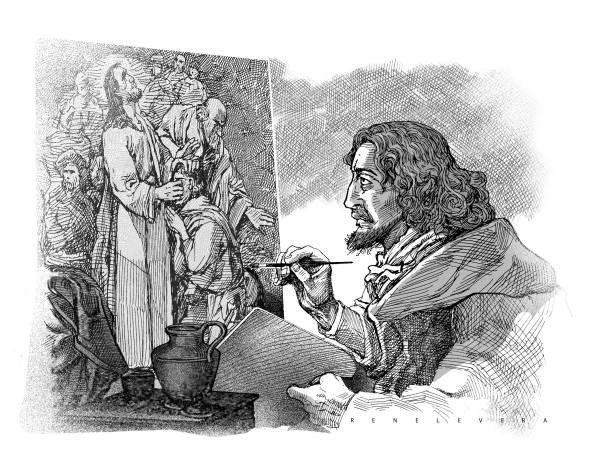

The painter Bartholomeus Breenbergh (1598-1657) lived during the Dutch Golden Age, which spanned the 17th century and saw the rise in the world of Dutch trade, science, military and art. He began training as a landscape painter in Amsterdam and then moved to Rome where he came under the spell of Italian landscapes. He returned to Amsterdam and there gained popularity for his paintings and etchings of Italian buildings.

The Louvre has a painting by Breenbergh entitled, “Jesus Healing a Deaf Mute.” No doubt, Breenbergh based this work on the Gospel of Mark, in which we read about Jesus:

“Again he left the district of Tyre and went by way of Sidon to the Sea of Galilee, into the district of the Decapolis. And people brought to him a deaf man who had a speech impediment and begged him to lay his hand on him. He took him off by himself away from the crowd. He put his finger into the man’s ears and, spitting, touched his tongue; then he looked up to heaven and groaned, and said to him, “Ephphetha!” (that is, “Be opened!”) And [immediately] the man’s ears were opened, his speech impediment was removed, and he spoke plainly. He ordered them not to tell anyone. But the more he ordered them not to, the more they proclaimed it. They were exceedingly astonished and they said, “He has done all things well. He makes the deaf hear and [the] mute speak.”

In the painting, we see a group of people around Jesus touching the ears and tongue of a deaf-mute kneeling on the ground. Breenbergh chose to depict the moment when the man began to hear and speak.

The artist, however, set the painting against the background of ancient Roman ruins, in accordance with the trend in Breenbergh’s time.

A family (man, woman and child) stand in the foreground, and near them sits a beggar. Perspective dictates that they appear larger than the principal scene – Jesus healing the deaf-mute – but the light that comes through a clearing in the clouds puts the focus on the latter. Breenbergh preferred landscapes to figure paintings, but here he exhibits a liking for the pictorial narrative, in particular to an incident from the Gospels.

The dark clouds parting to permit the light to brighten the principal scene serve as a parallel to the incident unfolding on the ground – Jesus healing a man deprived of hearing and speech, who now began to acquire the power of his senses; the Lord opening a door, which had kept him imprisoned in silence, to a world of sound and words.

What can we make of the man, wife and child in the foreground? They appear uninterested in the miracle unfolding in front of the ruins, unlike the beggar who intently looks at the event that has attracted a crowd. How much they resemble us, who, even when God’s action stares us in the face, cannot get ourselves to believe. The world and its values, our relentless daily concerns, could make us blind to the workings of the supernatural, which often transpire before us without our noticing them.

Breenbergh made the miracle part of the landscape. Somehow I find this a statement that miracles, which God brings about, happen in a natural setting, while we go about our tasks, but of course they take place not in the natural order or in accordance with natural principles.

Indeed, as George Bernard Shaw said, “Miracles, in the sense of phenomena we cannot explain, surround us on every hand: life itself is the miracle of miracles.”