I WAS awoken from a much-needed sleep that early evening of Tuesday, Feb. 22, 1986, by my boardmates who told me something big was happening in Manila.

As president of the Supreme Student Government (SSG) at the University of San Carlos, I was busy preparing earlier that day for the campaign to boycott products owned by cronies of the dictator Ferdinand Marcos. Candidate Cory Aquino had been in Cebu the day before, a Friday, to launch it at Fuente Osmeña.

As the university was already closed for the night and it was also a Saturday, I decided to wait out the brewing political storm in Manila and went back to sleep.

Early morning the following day, I began packing my things up. I had to be ready to end my life as an above ground anti-Marcos activist who started on this path way before the still-unsolved assassination of Benigno Aquino Jr. in 1983 polarized the country.

As activists, we were always told by our seniors in the protest movement to constantly prepare to hide should things turn bad. And the stalemate between Marcos’ loyalists and the tiny band of rebels at Edsa that Sunday morning, February 23, was not very encouraging. No one was even marching in Cebu that Sunday, a very eerily quiet day in Cebu.

The following day, Feb. 24, a Monday, I went to USC Main Campus at 8 o’clock and at the audio-visual center, I requested to turn on the public address system as I wanted to announce something. “My fellow Carolinians,” I began, “your student government is carefully taking stock of developments in Manila. Please stay in your classrooms and await further announcements.”

No sooner had I put down the microphone than some teachers, thinking I was calling for another protest march, brought their students down to the quadrangle, filling it in minutes. I had to do something fast. Many were now shouting to march to Camp Sergio Osmeña nearby but I was afraid what would happen there, knowing that the fate of Enrile, Ramos and the few men surrounding them at the camps on Edsa was as yet uncertain. We had no real-time social media, no Facebook to update us then.

Some members of the League of Filipino Students finally arrived and assured me they would cordon the students and teachers if I decide to march to Camp Sergio Osmeña, barely a kilometer away. I can still remember the faces of those students and even their teachers who were egging me to. And so we did.

At the camp, there was already a small crowd of curious onlookers as barricades of barbed wire had now been set up on the boulevard facing the camp gate. There were also the usual fire used to water us down in previous protest rallies.

One of my unforgettable anthropology teachers, Mrs. Zenaida Uy, who was the secretary-general of Bagong Alyansang Mabakayan (Bayan) Cebu at the time, was also there. So were Paul Rodriguez and other labor and opposition leaders. Everyone sat down on the pavement across the camp. By evening the crowd, like that at Edsa, had swelled so that I felt comfortable enough to go back to my dorm near Velez College to have dinner. When I came back later in the evening I was told that one movie actress wanted to be with the crowd that now stretched the length of Osmeña Boulevard but was booed. The actress had apparently campaigned for Marcos. Then someone from the Archdiocese sent loaves of bread for people to eat while sleeping overnight while monitoring the events at EDSA.

I went home near midnight to get some sleep. But I just couldn’t. My mind was racing, thoughts of “what if’s” crossing my mind because rebels holed up with Enrile and Ramos at Camp Aguinaldo were not that many. And somehow everyone had the nagging feeling that we would all be slaughtered.

And so even as I went back to the boulevard the following day, I was getting ready for my own exit from the city for parts as yet unknown.

Thankfully that did not happen as Feb. 25 unfolded with two opposing presidents were being sworn in, Marcos in Malacañang and Cory at the Club Filipino in Quezon City, even as more and more of the dictator’s forces were massing at Edsa to protect Enrile and Ramos. The tide was turning and by the afternoon, it was clear Marcos was no longer at Malacañang and therefore out of power.

The crowd at Camp Sergio Osmeña slowly dispersed, thinking that the end was over and that all the problems that Marcos and his ilk had brought upon the nation would not be solver. Life would be better and the Philippines would be great again.

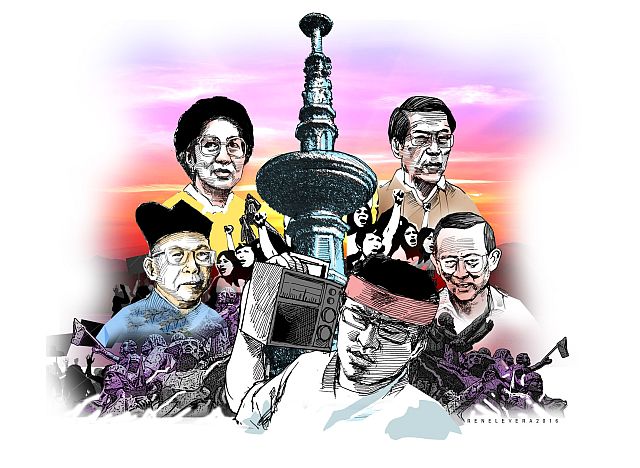

Thirty years on and the present generation barely remembers or knows Edsa and those days that finally united Filipinos, no matter if only in that brief historical moment, to oust powerful and entrenched dictatorship.

Today we even hear of revisionist versions of history: that the Marcos years were the best years this country has had ever. These are said mostly by the young who were not born in those most interesting of times; people who did not have to look over their shoulder and talk in whispers lest someone from the military hear your comment against Marcos.

In the ultimate analysis, we only have ourselves to blame as much as the leaders we elected to replace Marcos. For the so-called gains and hopes of Edsa remain as unreachable to the teeming masses of the poor as if that historical moment never happened.