I saw a donkey for the first time while studying in a foreign land, from which I sent a postcard of a long-eared jack to a friend, who reminded me of it when we met many years later as proof that our friendship had endured. But asses do not occur in this country very often. Besides, one of my favored books, — which someone borrowed and did not return, I mean the book — tells of a man and his donkey, Platero, as they go about their daily life in the Andalusian village of Moguer.

In that book, “Platero and I,” a Spanish classic authored by the poet Juan Ramon Jimenez, the narrator keeps a dialogue going between him and Platero, or perhaps just a monologue, because the donkey, although a first-rate listener because of the dimension of his auricles, could only bray. Which, incidentally, does not detract from the tenderness of their relationship — when he finds Platero limping, he looks for and finds a thorn in the donkey’s hoof and removes it while Platero nuzzles him.

One evening as they are going home, and they pass by a jenny, Platero’s “girlfriend,” Platero brays to her and hesitates to move on, a feeling which in a similar situation all of us share with animals. Master and donkey become friends with the parrot of a French doctor, which says nothing but “Ce nest rien!” (Forget it!)

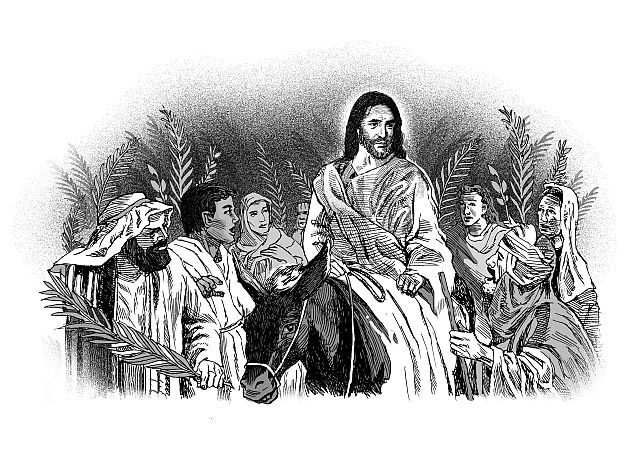

Parrot, though your name be Flaubert, I cannot forget Platero. I especially remember the ass on Palm Sunday, which commemorates Jesus’ entry into Jerusalem. In his Gospel, Matthew writes that, as they were nearing that city, Jesus sent two disciples to a nearby village where they would find an ass and her colt and to untie and bring them to him, saying to those concerned, “The Lord has need of them.”

When this was done, the disciples put their garments on the animals and Jesus rode on the donkey. The crowd laid their habiliments as well as the branches of trees on the ground for Jesus to pass on, and shouted, “Hosanna to the Son of David! Blessed is he who comes in the name of the Lord! Hosanna in the highest!”

Incidentally, the prophet Zechariah, living more than 500 years before Christ, predicted the event: “Rejoice greatly, O daughter of Zion! Shout aloud, O daughter of Jerusalem! Lo, your king comes to you; triumphant and victorious is he, humble and riding on an ass, on a colt the foal of an ass.”

Jimenez celebrates the donkey in his book, “Platero and I.” But the popular mind considers the donkey as an obstinate, stubborn, and intractable animal. St. Francis called his body Brother Ass, who must be given its needs — food, water, rest — but must be disciplined when it became an obstacle to the growth of his love for

God and neighbor. Nonetheless, in the end, St. Francis asked pardon from Brother Ass for treating it too harshly.

In G. K. Chesterton’s poem, “The Donkey,” the animal tells us how his appearance (monstrous head and sickening cry / And ears like errant wings) has earned him not a little ridicule despite that, like the rest of creation, it too has marvelous origins. But then, on the original Palm Sunday, when it carried the Son of God on its back, it had its moment of glory —

“Fools! For I also had my hour;

One far fierce hour and sweet:

There was a shout about my ears,

And palms before my feet.”