That it had to take a survey to confirm it is more surprising than the actual finding. One need only spend a few days with a closely knit farming or fishing community or watch the spate of local melodramas in which the protagonist is usually a poor person who finds happiness in the simple life to get at least a sense of the Filipino’s simple aspirations.

In his 1988 book “Waltzing with the Dictator,” author Raymond Bonner cited a Filipino sociologist who said that a typical Filipino would be content with a roof over his head, a plate filled with rice and fish on his table and a jug of tuba or local rice wine on one hand.

That description contrasts heavily with one of Bonner’s key subjects in his book, Imelda Marcos, whose infamous collection of shoes and wealth gained from years of ruling the country with her late husband and president Ferdinand Marcos belies a childhood steeped in poverty yet brimming with such fiery zeal to accumulate material wealth even at the expense of emptying the country’s coffers.

More than 30 years after the Marcoses fled, only to return in power with one of their own getting a real shot at reviving their glory days in the Palace, the Filipinos have to make a beeline outside the country to earn more for their families and sacrifice in the process the years and the times spent together, something which cannot be compensated by money and riches.

The survey which was conducted in March 2015 under the theme “Ambisyon Natin” (Our Ambition) also showed that more than 60 percent would rather live and work in the country than go abroad.

It also showed that Filipinos would rather take trips either domestic or abroad and that they prefer to live in small houses with big lots, provide their children with a college education and own a car to move around in.

Dreams or goals which actually fit a slightly upper middle class lifestyle in contrast to the 16 percent who want an affluent life and more than three percent who really want to be rich.

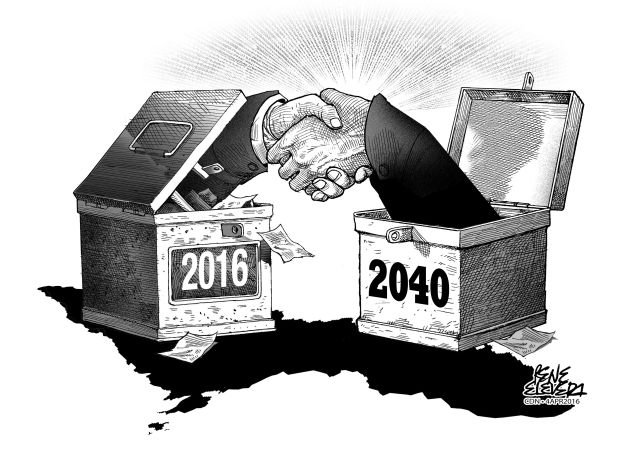

With the right policies and programs and the political will to implement them, the PCC and NEDA both believe that these aspirations can be achieved by 2040. Last time we checked, having dreams, chasing after them and fulfilling them are still considered an individual and collective right in this country that prides itself as Asia’s democracy.

Not only do we hope but we, the public, should hold those running for both national and local offices accountable in helping make these dreams and goals an achievable reality even before 2040.