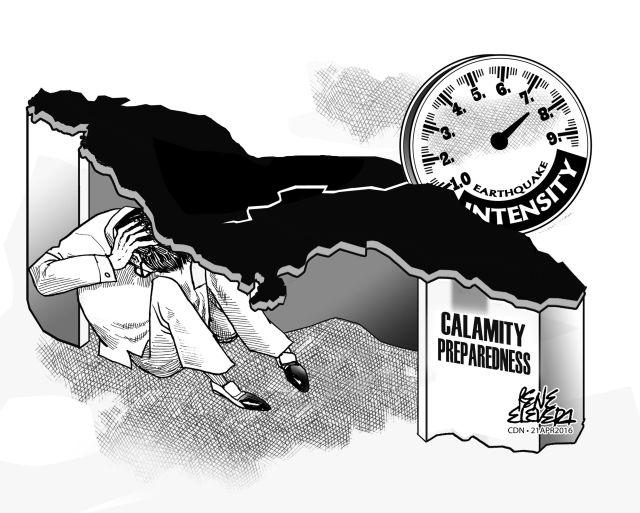

Today the Office of the Civil Defense and the National Disaster Risk Reduction and Management Council will hold the first of their quarterly nationwide earthquake drills, and the timing could not have been more inconspicuous.

As anyone who’s monitored the news knows by now, the earthquakes in Japan, Ecuador and Myanmar resulted in the deaths of hundreds and devastated homes and buildings.

In one report, Japanese authorities are said to be racing against time to rescue those buried under the rubble, a lot of whom are said to be children. Ecuador has mobilized hundreds of police and nearly its entire armed forces in search and rescue operations that are seen to last days, even weeks.

The Philippines has had its unenviable share of experiences with earthquakes, and in Cebu, the epicenters were located outside the province. The first was in Negros Oriental in Feb. 8, 2012. It registered a 6.5 on the Richter scale and lasted several seconds.

It didn’t cause serious damage, but it gained notoriety when a misguided blocktimer caused mass hysteria at Barangay Pasil all the way up to Fuente Osmeña by screaming something that sounded like “tsunami.”

It was later found out to much relief and consternation that the blocktimer actually referred to his daughter “Chona Mae.” He faced charges for causing public disturbance.

The second and more severe earthquake of Oct. 15, 2013 originated in Bohol province and caused majority of the damage there; but it didn’t spare Cebu and damaged the Pasil market and some church buildings.

It had been pointed out that were it not for the declaration of Eid’l Adha as a regular holiday on that date, schoolchildren and students would have been hurt or worse killed due to panic and the absence of enough safety exits in their school buildings.

Though the Philippine Institute of Volcanology and Seismology said the likelihood of yet another earthquake that was as strong or more severe than the 2013 quake may be lower, the seismic phenomenon’s unpredictability is what makes it dangerous.

The Japanese have made earthquake preparations an essential requirement for any civilian, and earthquake emergency kits are available in every public place and office building for use.

In Cebu City, there was supposed to be an assessment of the durability of old buildings in the downtown area. What happened to it, and was there anything significant done to implement the recommendations?

More importantly, are the people of Cebu ready to act in case they are hit with yet another earthquake — maybe not in the province but someplace nearby which can be strong enough to do more damage?

The news stories of the earthquake victims in Japan and Ecuador should spur Cebu’s local governments to do a better job of preparing their constituents in surviving quakes.