We usually associate the French artist Eugène Delacroix with “Liberty Leading the People,” a painting of armed Parisians surging forward, led by a half-clad woman representing Liberty. This work became the icon of the 1830 revolution, an event immortalized in Victor Hugo’s novel, Les Misérables.

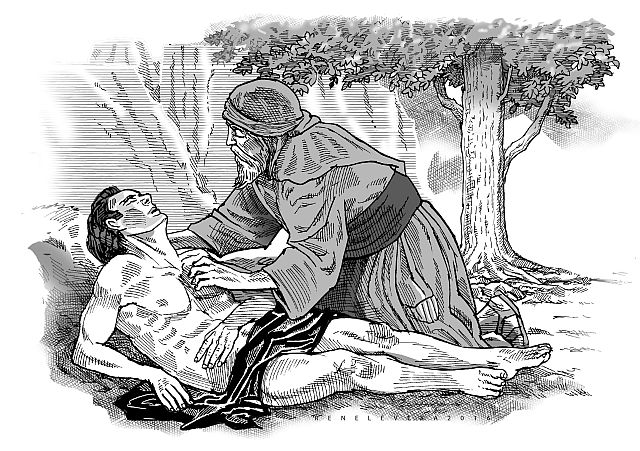

Delacroix had many paintings on biblical themes, too, prompting many to consider him the foremost religious artist of the 19th century. “The Good Samaritan” belongs to this group.

Delacroix bridged the gap between the classic and the modern, and greatly influenced the Impressionists. While “The Good Samaritan” displays Rubens’ impact on Declaroix in the latter’s marshaling of color and enfleshment of character (including the horse), the way his brush strokes convey movement and light presages the works of such as Monet and Renoir.

The painting in question displays both strength and tenderness. We know the story, of which Luke writes in his Gospel. A scholar of the law, wanting to test Jesus, asked him, “Teacher, what must I do to inherit eternal life?” Jesus questioned him back, “What is written in the law? How do you read it?” The scholar said, “You shall love the Lord, your God, with all your heart, with all your being, with all your strength, and with all your mind, and your neighbor as yourself.”

Undaunted, the scholar shot back, “And who is my neighbor?”

This question elicited from Jesus a parable, about a man who fell victim to robbers as he traveled down from Jerusalem to Jericho. The bandits stripped and beat him up and left him for dead. Two people – a priest and a Levite – just passed by him taking the opposite side of the road. But a Samaritan took pity, poured oil and wine over and bandaged the wounds of the victim, lifted and put him up on his horse and took him to an inn and attended to him there. The next day, before he left, he gave instructions to the innkeeper, giving him two silver coins, “Take care of him. If you spend more than what I have given you, I shall repay you on my way back.” Then Jesus asked the scholar, “Which of these three, in your opinion, was neighbor to the robbers’ victim?” Finding himself in a bind, the scholar replied, “The one who treated him with mercy.” And Jesus admonished him, “Go and do likewise.”

Samaritans and Jews hated each other. Hence, Jesus’ parable must have come as a shock to his listeners. Martin Luther King Jr., tried to explain why the priest and Levite did not help the victim. The man appeared dead, and so they had to stay away from him because touching a dead body made one unclean. And perhaps—because of the high incidence of robbery on the road between Jerusalem and Jericho—they feared the presence of bandits lying in wait, or a trap—the man merely feigning death and his companions just waiting on the sides ready to pounce on them.

They varied in their presumptions. The priest and Levite asked, “If I stop to help this man, what will happen to me?” Whereas the Samaritan asked, “If I do not stop to help this man, what will happen to him?”

Delacroix’s painting so impressed Vincent Van Gogh that, while convalescing in a mental hospital, he made a reproduction, a mirror image of it in his own style.

I like the idea of mirror image. How about if we consider a reverse mirror image of sorts. In the city, homeless people lie in a stupor in the alleys and on sidewalks. They do not differ from the traveler from Jerusalem to Jericho, except that they lie dying from the spasms of hunger rather than the violence of brigands. Such is the city that, more often than not, pedestrians, myself included, would just pass them by unconcerned.

Because they think only of their own comfort and safety, the pedestrians put themselves in a worse class than those who fade away from starvation. Both stand in danger of death, the latter from physical death, the former from spiritual, a worse kind of demise. If, despite their critical condition, the starving homeless realize this, and entrust the pedestrians to God so that He may have mercy on them and touch their hearts, they would become like the Good Samaritan in the parable. In tending with their prayers to the spiritual wounds of the uncaring crowd, they carry out the obligations of a true neighbor. And, who knows, the passers-by might turn around and help them.