Edwin Arlington Robinson published his poem, “Richard Cory,” in 1897. Whenever mention is made of this poet, people invariably think of this piece, together with another poem, “Miniver Cheevy.” The two are perhaps the most anthologized of Robinson’s poems.

When the wife and I co-taught literature in a girls’ high school, I gave “Richard Cory” to the class for study. The poem, very brief, just four four-line stanzas, goes as follows:

Whenever Richard Cory went down town,

We people on the pavement looked at him:

He was a gentleman from sole to crown,

Clean favored, and imperially slim.

And he was always quietly arrayed,

And he was always human when he talked;

But still he fluttered pulses when he said,

“Good-morning,” and he glittered when he walked.

And he was rich – yes, richer than a king –

And admirably schooled in every grace:

In fine, we thought that he was everything

To make us wish that we were in his place.

So on we worked, and waited for the light,

And went without the meat, and cursed the bread;

And Richard Cory, one calm summer night,

Went home and put a bullet through his head.[3]

The poem got the girls in a fluster. One and all asked this question — why did Richard Cory commit suicide? He had everything: looks, manners, wealth. And it did not help that the author left no clues in the earlier stanzas for the reader to expect the ending.

Of course, if Robinson wrote a dramatic piece, he would have to prefigure the suicide in some way according to a principle called Chekhov’s gun.

(Chekhov wrote: “If you say in the first chapter that there is a rifle hanging on the wall, in the second or third chapter it absolutely must go off. If it’s not going to be fired, it shouldn’t be hanging there.”)

But Robinson had a poem, not a play or a piece of fiction, in mind, in which he merely presented the facts, what the one speaking for the people of the town had observed of Richard Cory, of whom all that the reader knows bear only on the outside — how he dressed up, how he carried himself, how plentiful his pelf was. As to why, “one calm summer night,” Richard Cory “went home and put a bullet through his head,” the reader can only speculate. Much must have been building up inside him, which finally reached a detonation point. All that time, the struggle to survive must have so preoccupied the people of the town that they did not see signs in Richard Cory of this coming. But on the whole, the poem works with its powerful ironic ending.

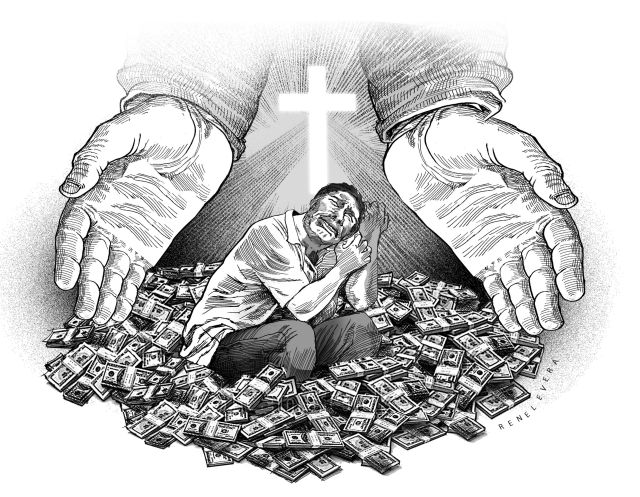

I find a character somewhat similar to Richard Cory in the Gospel of Luke, in a parable told by Jesus, popularly known as the Parable of the Rich Fool.

“There was a rich man whose land produced a bountiful harvest. He asked himself, ‘What shall I do, for I do not have space to store my harvest?’ And he said, ‘This is what I shall do: I shall tear down my barns and build larger ones. There I shall store all my grain and other goods and I shall say to myself, “Now as for you, you have so many good things stored up for many years, rest, eat, drink, be merry!”’ But God said to him, ‘You fool, this night your life will be demanded of you; and the things you have prepared, to whom will they belong?’ Thus will it be for the one who stores up treasure for himself but is not rich in what matters to God.”

We do not know exactly what happened to the rich man in the parable, except that he would die that night, and all the things that he had acquired and stored up would go to waste. What Jesus was driving at was that earthly treasures — money, power, honor, name — will all come to nothing, and that what counts is being rich in those things that matter to God, such as trust, courage, compassion, humility, service, generosity, justice.

At least the poem mentions that the people of the town, despite their hardscrabble life, “waited for the light” — hinting at a spiritual dimension to their existence. Light suggests hope, salvation. Richard Cory, despite his princely bearing, must have come to grief because he lacked this disposition, the hoping and waiting for the light — the true light that has come into the world.