The last had, in fact, been Adeste’s teacher when he took up fine arts at the University of the Philippines (UP) here in Cebu sometime in the 1980s. Abellana was a student ofAmorsolo during the prewar period in UP School of Fine Arts in Diliman, when it was still largely classicist in orientation.

Adeste descended from that lineage so it is not a surprise if his early work shows also some Amorsolo-esque characteristics.

One could note, for example, a slightly romantic approach in the portrayal of traditional Filipino rural life.

There is a strong sense of nostalgia for the beauty and simplicity of the life of simple folk in the countryside.

The artist freezes these moments in his paintings, making them timeless.

Timelessness and immutability are indeed the hallmarks of classical academic art, and this is exemplified by Adeste’s adherence to the same standards of proper depiction of human anatomy, perspective, light and shade, color theory, and techniques left behind by the ancient masters.

These qualities also account for what most people would call “realistic” art, a term that Adeste refuses to be attributed to his work.

“Actually the proper term is ‘naturalism’ since this is not photo-realism,” he says. Two years ago, Adeste surprised his followers and collectors when he came up with a solo exhibition entitled “Distortus” at Qube Gallery.

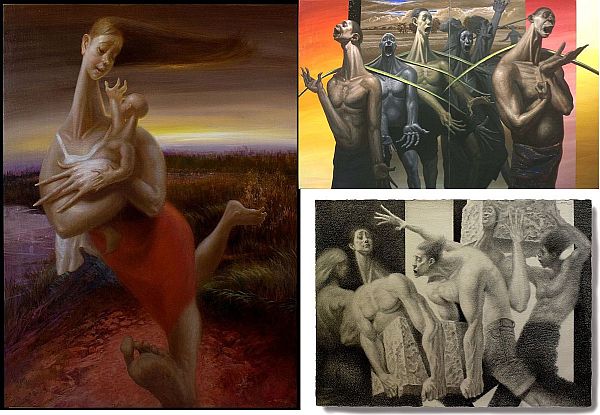

The series of paintings shows exaggerations or distortions in the representations of the human form and other objects in nature.

This seemed to be a sudden departure from his previous style.

The title comes from the Latin word “distortus,” which simply means distortion.

For Adeste, distortion in art permeated even the classical tradition, particularly during the late Renaissance as in the work of Michelangelo and the Mannerists like Tintoretto and El Greco who deliberately twisted and elongated their figures.

“Michelangelo was better than the Greeks in his execution of the human figure,” Adeste explains.

“But what I notice is that it was really an exaggeration of what the Greeks and the Romans did.”

Distortions in Michelangelo’s figures make them more emotionally expressive and they look like superheroes in Marvel and DC comics that Adeste imitated a lot in drawing as a child growing up in Basilan in Southern Mindanao.

Adeste refuses to be confined in his art. “I want to be able to express myself to the maximum,” he says.

“That’s why I resorted to distortion. I’ve been doing this before but only once in a while until I decided to have a full show with only this style of expression.”

The success of “Distortus” in 2015 inspired him to continue the style ina new series entitled “Distortus II,” which was held in Qube Gallery recently.

Some of the works in this exhibit were first shown in an art fair in Hong Kong, where the artist was brought there by Qube to represent Cebu.

“Distortus II” was segmented into three groups of work.

The first group consist of the big paintings entitled “Song of the Shoulder Pole People.” In this work, the artist pays homage to the lowly shoulder pole, which is commonly used by laborers worldwide to lighten their yoke.

Interestingly, the artist portrays the pole sans load, so that they appear like wings on the shoulders of workingmen, ironically turning them into a symbol of unbearable lightness.

“The subject is a very simple thing that is given prominence in the painting,” Adeste says.

“I amplified its importance.” The second group of paintings is the “Freedom Song” series, which was actually partly inspired by the issue of the West Philippine Sea.

But the work also delves on the basic elements of fire, wind, and water as implied in what artist calls “violators” or a detail that at first may seem to have no relevance or may even be disruptive in the composition but actually has a significant meaning. This series, whose title alludes to Bob Marley’s “Redemption Song,” is also a statement about freedom in every sense of the word.

And yet, the artist prefers to tone down its any political meaning.

He chose to color the violator image of a flame in either green or blue to cool it down, as ifto warn contending parties to deal with the problem with cooler heads. Still, it was purely incidental, according to him, that these paintings were first shown in Hong Kong, which is technically a part of mainland China.

The third section consists of mainly drawings done in mixed media (including coffee) and a painting that is the artist’s version of the Mother and Child theme.

The drawings, which reflects the power of “fidem” or faith among ordinary folk, exemplifies the artist’s proficiency in drawing in what-ever medium.

Drawing, which the Adeste considers “supreme” over painting, is the true strength behind his work.

The artist hopes to continue exploring new possibilities beyond “Distortus” although he admits that something in the past persists in his work.

Like Picasso, the classical spirit permeates in Adeste’s work in spite of what appears to be a turn towards modernism.

The classical spirit is evident in the sober temperament or the contemplative mood that the work evoke.

A viewer once commented that his distortion lacked “angst,” which inspired the wild exaggerations of German expressionism and other distorted styles of the modernperiod. “It became a language,” he says.

“Anyone can use that kind of language but not literally to express anger.” This preference for subtlety, restraint, and the contemplative enjoyment of beauty makes Adeste more of a classicist than a modernist. Indeed, the paradox that behind this surprise of the new is still the spirit of tradition.