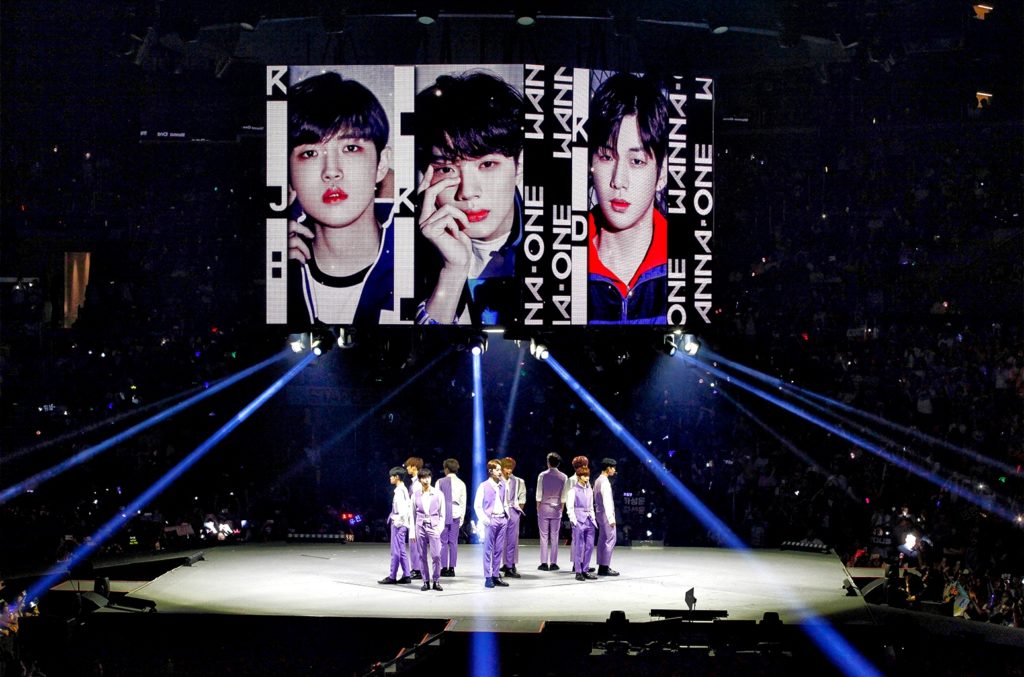

Members of the boy group Wanna One at the annual K-pop festival KCON at the LA Convention Center in Los Angeles on Aug. 11, 2018

INSIDE the Los Angeles Convention Center last weekend (Aug. 10-12), KCON, a yearly celebration of South Korean pop culture, saw 94,000 K-pop fans mob their favorite artists in meet-and-greets, dance like crazy in choreography workshops and bond over a music scene that has largely been built on the joys of fandom.

But in one convention center conference room, others were fully acknowledging that there is a darker, less discussed side of the K-pop lifestyle.

Last year, the singer Jonghyun of the K-pop group Shinee took his own life at 27. It devastated a corner of the music industry that had never really addressed the personal toll on artists, especially given its roots in a culture that values an intense work ethic and private resilience.

If depression and suicide could claim even one of the biggest stars in the genre, now, said some at KCON, was the time to talk about it.

“We can chip away at the stigma that there’s something wrong with us,” said Dr Andrea Bishop-Marbury, a therapist who spoke on the Saturday panel “K-pop and Mental Health”.

“If we can deal with ulcers, we can deal with the idea that mental illness is illness … We have to have compassion for ourselves before we can improve.”

It may have been the first time many in the crowd had heard this kind of candor at a K-pop fan convention. While KCON, founded in 2012 and now held annually in LA and New York, has long championed interaction between artists and fans (as well as behind-the-scenes peeks), this year’s event more overtly addressed realities beyond fandom. With the genre now firmly established globally, it felt right to begin asking some of these questions, and KCON dug into the truths of idol life, K-pop cultural appropriation and how gender dynamics shape the scene.

Over its six-year history, the festival has become the marquee K-pop event in the US. It is not only a one-stop shop for fans to see major K-pop acts that don’t often tour, but also a place to illustrate the genre’s increasingly broad pop-culture reach. And to be sure, the vast majority of it was as upbeat and devotional as ever.

During the day on Saturday, giddy fans waited in snaking queues to meet headliners Ailee, Twice and Wanna One, all of whom performed later that night at the Staples Center. They learned the intricate dances for hit singles like IN2IT’s SnapShot and Pentagon’s Shine. The weather was scalding, yet the mood was high.

But this year’s convention did begin to address some of the complex and often overlooked currents that get lost in all the fizzy fun of K-pop.

Members of groups like Block B and the mega-popular BTS have begun to allude to the pressures of K-pop stardom and the stresses of an industry that so tightly controls one’s public image and daily life. But after Jonghyun’s suicide, there is a new urgency to these questions.

Even though the mental health panel was mostly a primer for young fans who might not have had these conversations at home, it was valuable to say aloud that life’s struggles can be addressed in this scene.

Other panels talked about the specific appeal to, and the representation of, the LGBT community in K-pop, and the nuanced debts that K-pop has to drag culture. A talk on “black American music and K-pop” finally addressed what had been a running thread in the genre—much of it is indebted to US black music and culture, but rarely do the artists say so openly.

“A lot of K-pop artists appreciate black music, I just wish they’d acknowledge it more,” said Bruce “Automatic” Vanderveer, an American producer who worked on K-pop hits for Twice and Kim

Junsu. He lauded the collaborations between G-Dragon and Missy Elliott as a model for how to pay homage to this specific inheritance.

A video montage that paired K-pop music videos with their direct R&B and hip-hop reference points made it apparent. Tupac and 1Punch, Edwin Hawkins and BTS, Nicki Minaj and Laysha

—the K-pop acts’ looks, sounds and dancing all had direct connections to these artists. Most on the panel and in the crowd were more than fine with the allusions and culture-mixing. Ultimately, they just wanted K-pop culture— which, decades after the Korean war, already had a complicated relationship with American black influence—to cite their sources.

“Part of me gets upset because young fans don’t know the callback,” said Stephanie Choi, an ethnomusicology doctoral candidate at the University of California, Santa Barbara who studies K-pop, race and culture.

Crystal Anderson, a cultural studies scholar at Longwood University in the US state of Virginia, added: “These groups have long discographies where you can see the influence of

black music. It’s hard to talk about K-pop without talking about black influence.”

Of course, as the day turned to evening, the attention of fans turned too—from unpacking difficult and big ideas into seeing music that revelled in confetti, choreography and pounding dance tracks.

So while there is a lot of serious thinking being done about K-pop, identity and culture right now, KCON showed that after an introspective day for the genre, everyone was thrilled to get back to

the loud, ecstatic and unbridled joy of being a fan.