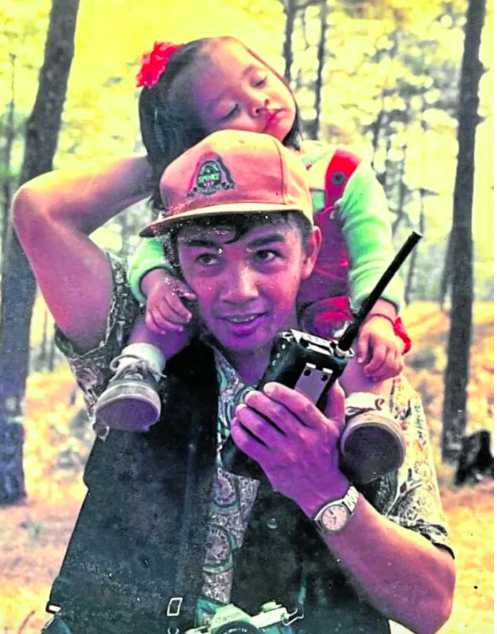

ADVOCACY | Artist Joel Arthur Tibaldo, who has revived “Eco Walk,” used to join city students hike through the Busol forest in the early 1990s with daughter Inah Felice on his shoulders, and eldest daughter Tam Jewel walking by his side. (Photo courtesy of the Baguio Media Newseum)

BAGUIO CITY, Benguet, Philippines — Artist and retired government employee Joel Arthur Tibaldo carried his then 2-year-old daughter, Inah Felice, on his shoulders when he joined grade school pupils wandering through an urban forest called Busol back in the 1990s.

His older daughter, Tam Jewel, was 4 years old and was walking beside him. Tam, now a 32-year-old protocol officer at the United States Embassy in Manila, said she had always been in awe of the huge pine trees towering above them.

Tibaldo brought his children to the first Eco Walk, an environmental experiment that turned city forests into nature “classrooms” for Baguio’s grade school pupils where they learned why Baguio trees need saving.

“I enjoyed being out and about, enjoying nature and its wonders, as well as meeting people and sharing the experience of ‘Eco Walk’ with them,” Tam said.

“My parents, my sister, and I visited Busol Watershed many times a year to walk around, draw, play, and plant trees. It wasn’t just us. There were other kids my age, and we were with local government officials and members of the media,” she added.

The records of grade school children who joined Tam, as well as other students who took part in Eco Walk across three decades, were lost after the death of the program’s longest overseer, journalist Ramon Dacawi, in 2019.

The community has sprung into action several times in the past whenever Baguio trees were threatened.

CITY OF PINES | Baguio City has become synonymous with the Benguet pine which thrives despite the intrusion of houses and buildings into the landscape. Residents have been extra protective about Baguio’s pine cover and have supported programs like “Eco Walk” which teaches children about the importance of protecting trees. (Photo by NEIL CLARK ONGCHANGCO / Inquirer Northern Luzon)

Protests

In 2012, the late Baguio Bishop Carlito Cenzon joined students, artists, and activists who camped outside a shopping mall to protest its expansion plan that would displace trees.

Seven years later, grade schoolers, backed by University of the Philippines Baguio students, formed a human chain around a 1-hectare patch of pine trees to prevent a national government agency from leasing that property to a developer. Pupils from the Baguio Pines Family Learning Center also sent a petition to then-President Rodrigo Duterte, asking him to spare the pine tree patch.

The conservation of the city’s pine trees began as a crusade with the formation in 1988 of the Baguio Regreening Movement (BRM), which was triggered by the start of water rationing.

Relaunch

Then Bishop Ernesto Salgado, BRM chair, “challenged” members of the Baguio Correspondents and Broadcasters Club (BCBC) to contribute to the environmental campaign, Tibaldo said, which was how “Eco Walk” was conceived.

After a five-year lull, “Eco Walk” was officially relaunched at Busol last month by Tibaldo, one of the local journalists who helped birth the project.

Tibaldo and foresters of the Baguio Water District welcomed women and children belonging to Partners for Indigenous Knowledge Philippines (PIKP), who were advised ahead of the trip to wear comfortable walking shoes, carry their own water and pack gloves and gear for the tree-planting activity.

about pine trees and later joined parlor games like finding the longest pine needle at Busol. (Photo by JOEL ARTHUR TIBALDO / Contributor)

PIKP members went through the traditional orientation program, including a parlor game to select the longest pine needle, and attended lectures about the environment.

Tibaldo said the task he inherited from Dacawi brought him full circle to the time he, Dacawi, the late editor Peppot Ilagan, journalist March Fianza and Inquirer correspondent Nathan Alcantara “brainstormed” the Eco Walk concept in 1992. The program was enhanced further by then Community Environment and Natural Resources Officer Guillermo Fianza and teachers Victoria Candelario and Carmelita Simsim, as well as former BCBC presidents.

Ilagan used to credit the “walkabout” for the Eco Walk philosophy. Like this traditional rite of passage in Australian aboriginal society, where adolescent males live in the wilderness, “Eco Walk” is intended for children to reflect on the value of nature as they journey through the woods.

But an old Eco Walk manual that Tibaldo managed to preserve also refers to indigenous forest management systems like the “muyong and pinugo of Ifugao, the tayan and batangan of Mountain Province and the lapat of Apayao” as the program’s inspirations.

Philippines, including children, plant pine tree saplings at Busol on May 22, 2023, to help regenerate this watershed. (Photo by JOEL ARTHUR TIBALDO / Contributor)

Young activists

Alcantara said Dacawi and Ilagan tapped pupils of the Rizal Elementary School, who were the pioneer Eco Walkers. More schools joined with the help of the late Abner Villanueva, who was then the spokesperson of the Department of Environment and Natural Resources Cordillera, he recalled.

The Eco Walk manual describes Baguio’s predicament as “dire.”

According to the manual, despite massive reforestation efforts, the forest cover hardly improved simply because the programs could not ensure a high survival rate for the seedlings planted.

“Forest fires, tree poaching, and intrusions by illegal occupants have contributed to the denudation of the city’s watersheds. It has resulted in a critical water shortage and the warming of a once scenic region of pines that used to enjoy a year-round temperate climate,” it says.

“Children are the key players because they are most capable of being molded to become lifetime environmentalists. They are chosen because they will be affected the most by the quality of the environment that they will inherit,” it adds.

PIONEER | The late journalist Ramon Dacawi was the longest overseer of Eco Walk. (Photo courtesy of the Baguio Media Newseum)

Tam accompanied Dacawi in China when Eco Walk’s environmental achievements earned it the Global 500 Award by the United Nations Environment Programme in 2002.

She said Eco Walk was incorporated into many other projects, as children used to be joined by the city’s “Lucky Summer Visitors,” who were first-time Baguio guests which BCBC selected annually during the Holy Week break.

The program’s revival comes at a time when Baguio Mayor Benjamin Magalong authorized a crackdown on new structures rising within Baguio forestlands, including Busol, for the city’s self-preservation.

Busol is a major city watershed that is occupied by settlements, some of which belong to Baguio Ibaloy families.

The city currently has 2.5 million trees, of which only half a million are Benguet pine, based on an inventory ordered by then Environment Secretary Roy Cimatu. The number has since risen by 50,000, according to the City Environment and Parks Management Office.

A 2019 urban carrying capacity report reveals that “the measured forest cover [of Baguio] remains only at 20 percent of the total area of the city which is below the 40 percent standard,” and the consultancy group Certeza Infosys asserted that “massive reforestation and protection of forest reservations are urgent measures.”