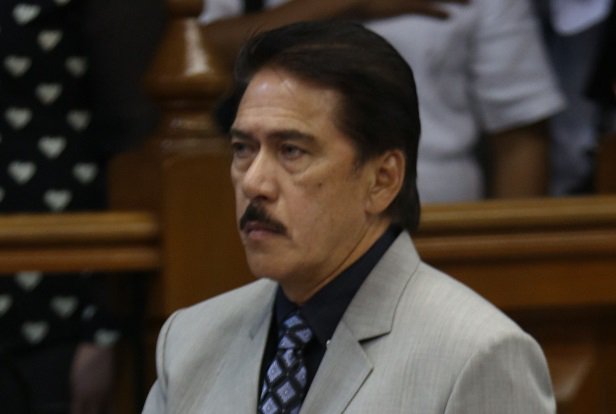

SOTTO

Amid the rising body count in the Duterte administration’s war on illegal drugs, Senator Vicente “Tito” Sotto III said reports of extrajudicial killings (EJK) in the Philippines were mere conjectures and that all drug suspects who ended up dead in police operations were killed because they resisted arrest.

Speaking before about a hundred policemen in Cebu yesterday, the Senate majority leader said drug suspects who were killed by the police comprised just five percent of statistics in the government’s illegal drugs campaign.

“I never fail to smile every time they mentioned the issue of extrajudicial killings. Just look at the stats. It’s really the way you picture things,” Sotto said in his speech during the celebration of the Drug Abuse Prevention and Control Month at Camp Sergio Osmeña, the Police Regional Office in Central Visayas (PRO-7) headquarters based in Cebu City.

And even as the Senate investigation on EJKs is still underway, Sotto appeared to have made up his mind: All those killed had engaged the operatives in shootouts, he told participants of the forum in Cebu.

According to records of the Philippine National Police (PNP), at least 37,346 anti-drug operations were conducted nationwide from July 1 to Dec. 1.

At least 38,587 drug suspects were arrested while 2,004 were killed, the records stated.

The figures do not include those who died in the hands of unknown assailants since President Rodrigo Duterte assumed office.

Sotto lashed out at international publications and broadcast networks that have reported about the rise in killings of suspected drug users and pushers in the Philippines.

Last October, The Liberation, a French newspaper, tagged President Duterte as a “serial killer president” amid the series of killings in the administration’s relentless war on drugs.

International publications like The Guardian, TIME Magazine, The New York Times and the Washington Post and broadcast networks like CNN also previously featured Duterte’s war on drugs, raising alarm over the spate of unsolved killings.

Duterte and Malacañang Palace’s communication’s team have repeatedly criticized the foreign media for allegedly “spinning” his statements.

But as far as Sotto was concerned, statistics proved that majority of drugs suspects in the country were given the chance to live.

“If only the international media could highlight the total picture, it will be a different story. They have made a maling akala (wrong notion) on what is happening in the Philippines today. There’s a misinterpretation of things that are happening,” he said.

Sotto said President Duterte was “mesmerized” and “concerned” about the proliferation of illegal drugs in the country.

“He did not expect it. He thought the strategy he used in Davao will work in other cities. He did not realize the enormity of the problem until he became president,” he said.

Sotto said he advised the President to take things one step at a time in order to succeed in the anti-drug campaign.

For this reason, he said the Senate investigation was first directed against drug lords in the Visayas and the National Capital Region.

“These are the big regions. But that does not mean we won’t look into illegal drugs operations in the other regions,” Sotto said.

CUENCO

Five months after President Duterte started the war on drugs, Sotto said he is now seeing change in the country’s peace and order.

“The Philippines is a very beautiful country. Now, people who come here are no longer afraid of drug addicts roaming around different places. There are still those who are into illegal drugs, that is why our efforts should be continued,” Sotto said.

For their efforts in eradicating illegal drugs, Sotto gave plaques of recognition to city and provincial police directors in Central Visayas, Dr. Alice Utlang of the Cebu Office for Substance Abuse Prevention Program, and Captain Ernie Manatad of Barangay Subangdaku for implementing a community-based drug rehabilitation program.

Death penalty

Sotto also called for the reimposition of death penalty for “high-level” drug traffickers, and to amend the Anti-Wiretapping Law to allow the use of modern communications equipment in surveillance operations against suspected drug personalities.

In 2014, Sotto sought the revival of the death penalty law through lethal injection when he authored Senate Bill No. 2080, which proposed to repeal Republic Act No. 9346 or “An Act Prohibiting the Imposition of Death Penalty in the Philippines.”

“Hopefully, with the help of Congress, we will be able to help the President and the country. We will try our best to address our main problem which is peace and order,” he said.

Sotto expected human rights groups and the Catholic Church in the country to oppose the plan.

“If (the death penalty will) only be for high-level drug trafficking, there’s a chance that we are going to make it. But if we include other crimes, I doubt (if) we will finish it in due time,” the senator said.

Sotto said there was a need to revive the death penalty for high-level drug traffickers to frighten violators and to prevent them from operating in the country.

“Like the sword of Damocles, it will prevent manufacturers to use the Philippines, not only as a transshipment point, but also as a manufacturing area of illegal drugs,” he said.

While Asian countries like Singapore, Malaysia, China and Indonesia have existing death penalty laws, the Philippines, which Sotto described as the “center or crossroad of drug trafficking in Asia,” has none.

Former Rep. Antonio Cuenco of Cebu City’s south district, one of the authors of the anti-drugs law, supports Sotto’s calls to revive the death penalty.

“The imposition of death penalty, under the present circumstances, is really better. It’s more justified than the so-called extrajudicial killings,” Cuenco said.

“So that the world would stop criticizing us, let’s restore the death penalty for those found guilty by the court on illegal drug trafficking. Let’s restore the death penalty and let the law take its course. Patyon nato ang mga drug traffickers apan pinaagi sa balaod (Let us kill the drug traffickers within the bounds of the law),” Cuenco added.

Cebu Archbishop Jose Palma, in an earlier interview, said bringing back the death penalty will not reduce crimes and expressed hope that President Duterte will not allow it.

Dr. Rene Bullecer of Human Life International said he and Sotto are friends, but he won’t support the senator’s plans to revive the death penalty.

“I’m sorry. We can’t support him on this. A real pro-life advocate respects life from its inception to the last breath,” he told Cebu Daily News over the phone.

PALMA

“Even if it targets high-level drug traffickers, that (death penalty) is still a crime against humanity; a very cruel penalty at that,” he added.

Between 1946 and 1965, under President Ferdinand Marcos, 35 people convicted of savage crimes were executed.

After the EDSA People Power Revolution that toppled the dictator from power, then president Corazon Aquino promulgated the 1987 Constitution and abolished the death penalty “unless for compelling reasons involving heinous crimes, Congress hereafter provides for it.”

In March 1996, under President Fidel V. Ramos, the law, through Republic Act 8177, was amended prescribing death by lethal injection for offenders convicted of heinous crimes.

Between 1999 and 2000, during the term of President Joseph Estrada, seven inmates were put to death, one for raping his daughter more than a hundred times over two years starting when she was 16.

Former president Gloria Macapagal-Arroyo abolished the death penalty in 2006, explaining that death penalty had not proven to stop crimes.

Wiretapping

Sotto, meanwhile, also wants to amend Republic Act No. 4200 or the Anti-Wiretapping Law to allow the use of wiretapping and modern communications equipment in surveillance operations against drug traffickers, pushers and the like.

“This law is outdated. We have to update it, of course, with the proper safeguard. There must be certain provisions of who should be wiretapped because the existing law has many prohibitions even including drug lords,” he said.

He said the Anti-Wiretapping Law, which was enacted in 1965, frustrates police and prosecutors in convicting drug traffickers by limiting the evidence that can pin them down.

The law allows wiretapping for cases of treason, espionage, rebellion or sedition, and kidnapping. But wiretapped communications not ordered by a court are inadmissible evidence.

“Imagine if we were able to wiretap all the transactions done inside the National Bilibid Prison. Even if they used cellphones, (we can still monitor them). Without an order from the court, we could not wiretap communications. And by the time we secure an order, the illegal transaction we wanted to know is over,” he said.

Sotto also encouraged barangay leaders to help law enforcers in their illegal drugs operations, particularly those who are members of the Barangay Anti-Drug Council (Badac), which was created under the Comprehensive Dangerous Drugs Act of 2002 to empower village officials to assist law enforcers in running after drug syndicates.

Disclaimer: The comments uploaded on this site do not necessarily represent or reflect the views of management and owner of Cebudailynews. We reserve the right to exclude comments that we deem to be inconsistent with our editorial standards.