‘Night fell’: Hong Kong’s first month under China security law

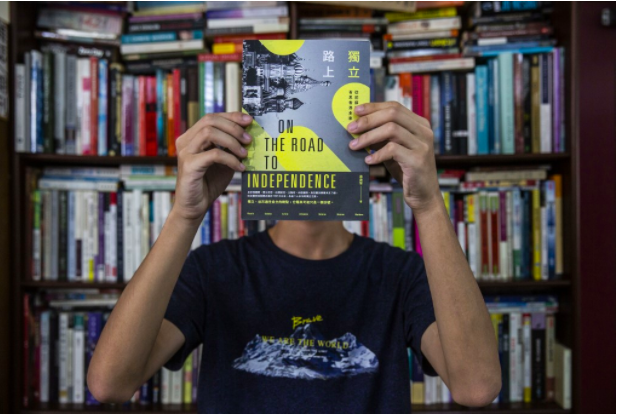

This picture taken on August 8, 2020 shows teenager Tony Chung holding up a copy of a book that police seized as evidence from his home when he was arrested under the new national security law, at a bookstore in Hong Kong. (Photo by ISAAC LAWRENCE / AFP) / TO GO WITH HongKong-China-politics,FOCUS by Su Xinqi and Jerome Taylor

HONG KONG, China — Teenager Tony Chung said he was walking outside a shopping mall when police officers from Hong Kong’s new national security unit swooped, bundled him into a nearby stairwell and tried to scan his face to unlock his phone.

Chung’s alleged crime was to write comments on social media that endangered national security, one of four students — including a 16-year-old girl — detained for the same offence that day.

The arrests were made under a sweeping new law Beijing imposed on Hong Kong in late June, radically changing the once-freewheeling business hub.

Chung describes the law in stark terms.

“I think night just fell on Hong Kong,” the 19-year-old told AFP after his release on bail, the investigation ongoing.

A political earthquake has coursed through the former British colony since the national security law came into effect on 30 June.

Under the handover deal with London, Beijing agreed to let Hong Kong keep certain freedoms and autonomy until 2047, helping its transformation into a world-class financial centre.

The security law — a response to last year’s huge and often-violent pro-democracy protests — upended that promise.

Last week the United States placed sanctions on Chinese and Hong Kong officials, including city leader Carrie Lam.

‘A second handover’

Despite assurances that the law would only target an “extreme minority”, certain peaceful political views became illegal overnight and the precedent-setting headlines have come at a near-daily rate.

“The overnight change was so dramatic and so severe, it felt as momentous as a second handover,” Antony Dapiran, a Hong Kong lawyer who has written books about the city’s politics, told AFP.

“I don’t think anyone expected it would be as broad-reaching as it proved to be, nor that it would be immediately wielded in such a draconian way as to render a whole range of previously acceptable behaviour suddenly illegal.”

The law itself was new territory.

It bypassed Hong Kong’s legislature — its contents kept secret until the moment it was enacted — and toppled the firewall between the mainland and Hong Kong’s vaunted independent judiciary.

China claimed jurisdiction for some serious cases and enabled its security agents to operate openly in the city for the first time, moving into a requisitioned luxury hotel.

Officially the law targets subversion, secession, terrorism and colluding with foreign forces.

But much like similar laws on the mainland used to crush dissent, the definitions were broad.

Inciting hatred of the government, supporting foreign sanctions and disrupting the operation of Hong Kong’s government all count as national security crimes, and Beijing claimed the right to prosecute anyone in the world.

Hong Kongers did not have to wait long to see how the letter of the law might be applied.

The first arrests came on 1 July, the anniversary of Hong Kong’s handover, mainly against people possessing banners or other objects carrying pro-independence slogans.

One man who allegedly drove a motorbike into police while flying an independence flag was the first to be charged — with terrorism and secession.

The law was felt in many other ways.

Schools and libraries pulled books deemed to breach the new law. Protest murals disappeared from streets and restaurants. Teachers were ordered to keep politics out of classrooms.

Local police were handed wide surveillance tools — without the need for court approval — and were given powers to order internet takedowns.

On Monday Jimmy Lai — a local media mogul and one of the city’s most vocal Beijing critics — was arrested under the new law along with six other people, accused of colluding with foreign forces.

Political crackdown

The roll-out combined with a renewed crackdown on pro-democracy politicians.

In July, authorities announced 12 prospective candidates, including four sitting legislators, were banned from standing in upcoming local elections.

They were struck off for having unacceptable political views, such as campaigning to block legislation by winning a majority, or criticising the national security law.

City leader Lam later postponed the election by a year, citing a sudden rise in coronavirus cases.

Three prominent academics and government critics lost their university jobs.

Media started having visa issues including The New York Times, which announced it would move some of its Asia newsroom to South Korea.

Gwyneth Ho, one of the disqualified election candidates, described the security law’s suppression of freedoms as “obvious and quick”.

“We are now in uncharted territory,” she told AFP.

Nonetheless, Ho remained optimistic.

“The people’s fighting spirit is still there, waiting for a moment to erupt,” she said.

“Hong Kong people have not surrendered.”

Disclaimer: The comments uploaded on this site do not necessarily represent or reflect the views of management and owner of Cebudailynews. We reserve the right to exclude comments that we deem to be inconsistent with our editorial standards.