Because in my awareness it has unclear beginnings, the sea seems for me to have always been there, its tides constantly washing the town’s boulevard and market walls. I asked no reasons for it – it was as gratuitous as the air and sun, as the weather.

Every so often, my brother and sisters would pass the time wading the tide pools, and the accidental prominence under our bare feet of a bivalve or two really warmed the cockles of our hearts.

There was an islet not far from the town, which a narrow wooden bridge attached to the mainland. It had no name except “pulo,” the generic native term for island. All of its residents were fishermen – naturally, the patron saint of the place was St. Peter, on whose feast day a boat race was held, a spectacle anticipated and watched by most everyone in the town.

More than this, it was the place itself that pulled me there even on ordinary days. The fact that islands fascinated me, that it was the island closest to home, and that its residents so differed from the rest of the people of the town as to be an island in themselves.

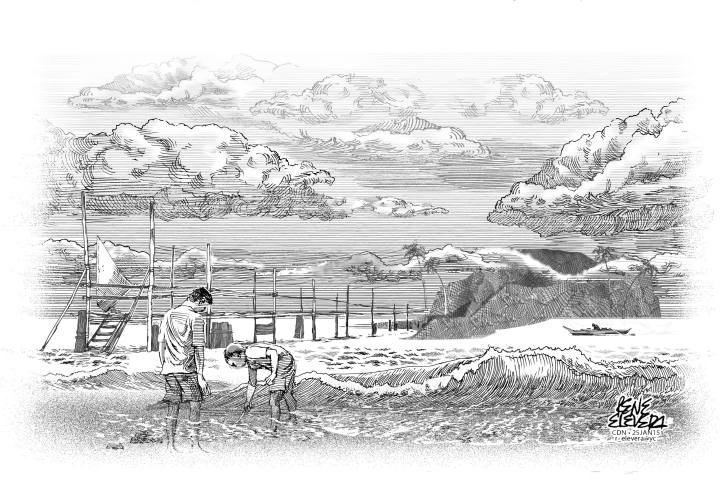

I particularly liked the sight of the boats that were beached after a night of fishing, and the quiet, constant activity of the folk – the women going about their house tasks, and the men fixing the boats and mending the nets, those who were not inside the huts sleeping to store up their energies for after sunset when they would set out to sea again.

This was roughly the same scene that Mark describes in his Gospel after John the Baptist had been arrested and Jesus came to Galilee to proclaim the Good News.

“This is the time of fulfillment,” Jesus said. “The kingdom of God is at hand. Repent, and believe in the gospel.”

As he passed by the Sea of Galilee, Jesus saw Simon and his brother Andrew casting their nets into the sea and said to them, “Come after me, and I will make you fishers of men.”

A little farther, Jesus saw James, the son of Zebedee, and his brother John, who likewise were in a boat mending their nets, and he called them too.

Mark tells us that all four of them – Simon, Andrew, James and John – dropped whatever they were doing and followed Jesus.

Jesus began his work of salvation in earnest beside the sea, or lake, with fishermen among the nets and boats.

On that small island, there was only silence, as my brother and I walked about taking stock of the surroundings. (Truly, to be a child is to be, as Christopher Isherwood put it, a camera with its shutter open.)

There, on the island, where human conversation was minimal, life was a dialogue between land and sea, although the image that comes to me is of land as mouth thrusting its lips towards the sea to sip the water wave after wave. Nonetheless, the sounds the wind carried had for me the character of a call, the equivalent of which the four apostles, who were fishermen, must have heard. This must have been the reason why they did not hesitate to follow Jesus – that already they had heard his call in the call of another, a vaster sea.

Disclaimer: The comments uploaded on this site do not necessarily represent or reflect the views of management and owner of Cebudailynews. We reserve the right to exclude comments that we deem to be inconsistent with our editorial standards.