About waiting, I ask myself what my most memorable experience of it would be. At my age, I should be able to recall not just one but many.

About waiting, I ask myself what my most memorable experience of it would be. At my age, I should be able to recall not just one but many.

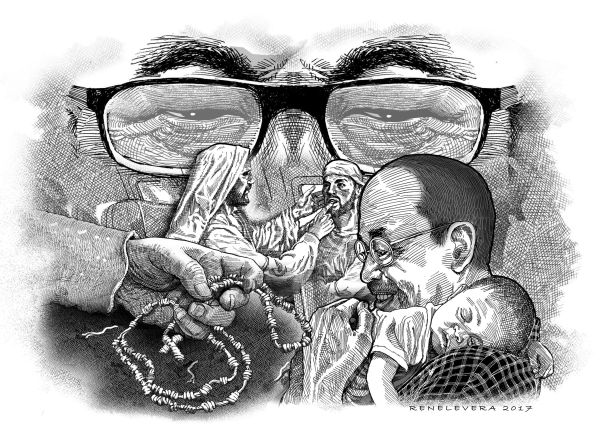

There were joyful waitings, of course, the most recent being for the birth of a granddaughter, the time leading to which the wife and I spent in prayer in the chapel of the hospital, and when our son-in-law texted us that the baby was born, our happiness was such that we hastily cut short our petitions and rushed to the nursery to view the infant for the first time.

There were sad waitings, of course, of which the less said, the better.

Waiting is a state of mind, an attitude. If I feel that it is forced on me and resent it, I am not really waiting, but enduring, and therefore incapable of being at peace during the hours before the arrival of someone or the happening of the event.

And even if I am not sure what the outcome would be — as when I wait for the results of a biopsy — I can still be serene through prayerful surrender and resignation.

Life itself is a waiting. But one can just let the days pass without anything significant happening, and one remains the same to the last moment. Or one can spend the time in mindless pursuits and end up the worse for it.

Waiting requires attentiveness because even in activity one can just follow the routine and remain closed to the things that matter. Waking requires contemplation.

Perhaps this is the message that underlies the passage in the Gospel of Mark, in which Jesus said:

“Be watchful! Be alert! You do not know when the time will come. It is like a man traveling abroad. He leaves home and places his servants in charge, each with his work, and orders the gatekeeper to be on the watch. Watch, therefore; you do not know when the lord of the house is coming, whether in the evening, or at midnight, or at cockcrow, or in the morning. May he not come suddenly and find you sleeping. What I say to you, I say to all: ‘Watch!’”

And so we wait. But do we know what we are waiting for? Or is our waiting no different from that in Samuel Beckett’s play, “Waiting for Godot.”

There, the two characters, Vladimir and Estragon, wait for someone who never arrives.

In that play, nothing happens except the verbal exchange between Vladimir and Estragon, as well as with three other characters that merely come and go.

This reminds me of a short story by Grace Paley, “My Father Addresses Me on the Facts of Old Age.” Again, nothing happens in this story, which similarly is a dialogue — between an aging father (a Russian Jew, who was a widower and retired physician) and his daughter (married, with children, and on the brink of a divorce).

In the course of the conversation, we learn about the old man’s life, that he was an atheist, whose sympathies lay with the Russian Revolution, and liked reading Turgenev.

This is the advice he gave his daughter about life — “The main thing is this — when you get up in the morning you must take your heart in your two hands. You must do this every morning.” In other words, she must talk to her heart every day.

The old man lived for the moment, but clearly he waited for something or someone — certainly, the daily morning visit of his wife who died of breast cancer, and who had vainly pleaded with him to be taken from the hospital to die at home, as well as for the off-chance of reconciling with his brother, who was deported back to Russia.

Of the morning visit, the daily taking of the heart in the hands, Cardinal Basil Hume had his version. “There are times when I can visualize Our Lord at the break of day standing by my bed and saying: ‘Get up, follow me.’”

Jesus himself leads us in waiting for him, for his coming in judgment at the end of time. And so I wait — with alertness, I hope, and in prayer and contemplation, knowing that my waiting is for someone who already is here, whose Resurrection has brought me to the eternal present, that which St. Augustine calls “the now that does not pass away.”

Disclaimer: The comments uploaded on this site do not necessarily represent or reflect the views of management and owner of Cebudailynews. We reserve the right to exclude comments that we deem to be inconsistent with our editorial standards.