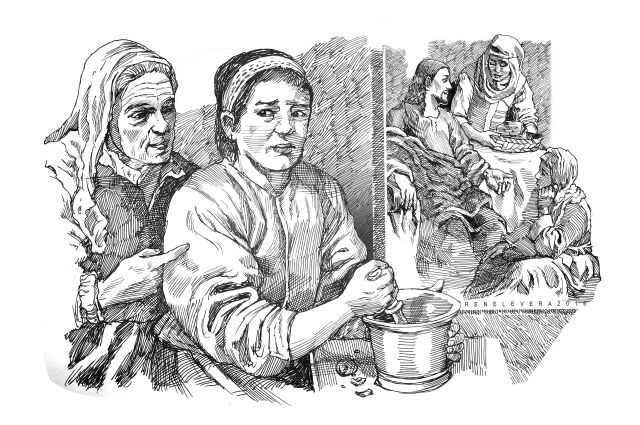

In 1618, the Spanish artist Diego Velázquez painted “Christ in the House of Martha and Mary.” The work, done in oil on canvas, depicts two women in the kitchen, one young, the other elderly. The young woman, a maid, looks distraught as she grinds garlic in a mortar to make a mayonnaise to go with the fish, which we see laid out on the table together with the eggs and garlic. The elderly woman admonishes her as she points to a frame or window to their left, which shows a scene from the Gospel of Luke, in which Jesus counsels Martha, who complains about his sister Mary sitting in front of Jesus to listen to him speak instead of helping her in preparing a meal. “Martha, Martha,” Jesus says, “you are worried and upset about many things, but only one thing is needed. Mary has chosen what is better, and it will not be taken away from her.”

What troubles the maid? Does she feel smothered by her many tasks? Well then, the old woman seems to remind her of the story of Martha and Mary, of its moral about work, which, no matter how important, cannot quite satisfy the human heart, which finds rest in God alone. The painting and the story focus on the tension between the spiritual and the temporal, on the primacy of the first, the vita contemplativa, over the second, the vita activa.

Velázquez tried out a genre called bodegones, in which he linked Biblical themes with contemporary Spanish life. (In Spanish, bodega means pantry, tavern or wine cellar. Bodegon arises from bodega and can mean a still-life painting that details the items of a pantry, such as fruit, fish and poultry.)

Many consider the maid as Martha herself and the old woman as merely an incidental character. In which case an actual window frames the biblical scene, and the maid gets everything ready for the meal with the Lord.

On the other hand, it could happen that the kitchen has a framed painting hung on its wall, and this would be in line with the intent of bodegones to depict the Spain of the day. Interestingly enough, the restoration of the painting done in 1964 revealed that a window in the wall opens to the biblical scene, which supports the view that Velázquez–known for his interest in layering, in presenting “paintings within the painting”–really painted Martha as maid.

Commentators say that, in the incident narrated by Luke, Jesus talks not so much about Martha’s being busy as about her being distracted, her being “worried and upset about many things.” In the presence of a guest, one does not turn one’s back to him or her. Instead, one keeps the guest company (as much as possible directing the help to make the arrangements for the meal). One’s task as host is to be attentive and listen to the guest, which Mary does.

We have no way of knowing what exactly the elderly woman in the painting is saying to the maid. She, however, points to the scene of Jesus, Mary and Martha. Were the three just in the painting or actually present in the next room? Nonetheless, we can take it that the elderly woman alludes to the periodic need of finding time to step aside from her chores and in solitude catch up with her soul–in silence to contemplate the words and speak to Jesus.

In fact, she does not have to drop her work in order to do this. One can turn one’s work into prayer by, in the words of the Little Flower, St. Thérèse of Lisieux, doing “small things with great love.”

This was likewise the method of Brother Lawrence, a 17th-century monk who worked as a cook in a monastery. For him, the time for action did not differ from the time of prayer because he strove always to keep within himself a sense of the presence of God.

Velázquez’s maid has a choice, either to look at the scene of Mary and Martha through a hole, as actually happening in her life, in which case she cannot escape acting out the role of one or the other, or to regard it as merely a painting hanging on a wall, something she can be indifferent to and very well ignore. Then her anxiety would stem from other causes, from her mind being far from what she is doing, and she would purely be Martha and no one else. She fails to realize that she can be both Mary and Martha, and that, as a book by Joanna Weaver puts it, she can have a Mary heart in a Martha world.

Disclaimer: The comments uploaded on this site do not necessarily represent or reflect the views of management and owner of Cebudailynews. We reserve the right to exclude comments that we deem to be inconsistent with our editorial standards.