Source: Dulaang UP

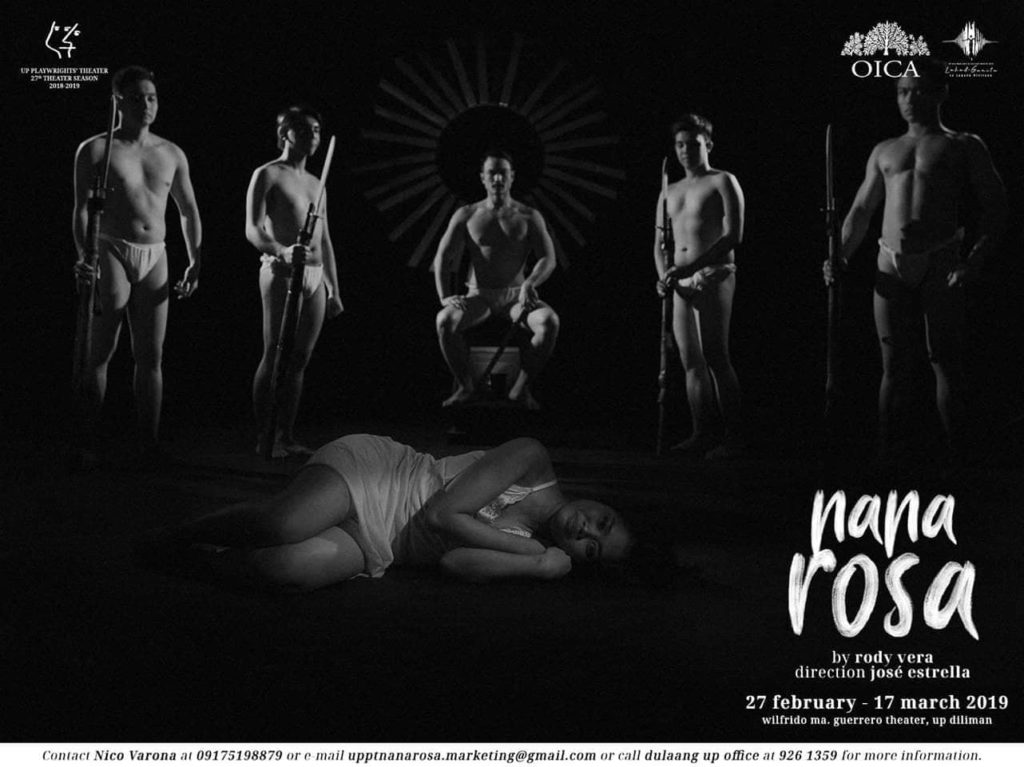

“GINAHASA AKO.” The words that Nana Rosa Henson writes every day in a piece of paper but she then crumples and throws away to hide her dark past.To many, the memories of World War II are dim, made dimmer by the passing on of the grandmothers and grandfathers who lived through the horrors of that war.Written by Rody Vera under the direction of José Estrella, Nana Rosa recounts on stage the life of Maria Rosa Henson, the first Filipino comfort woman to come forward with her story in public — starting from her early life, to her capture and eventually her becoming a comfort woman, liberation, and finally deciding to tell her story nearly fifty years later.

On the occasion of the 80th year anniversary of the start of World War II, this UP Playwright’s Theatre work underscores that some traumas are so severe that, though the mind tries to forget, the feeling always remains. Memories become hazy and details are forgotten, but sometimes out of nowhere, like a dam breaking, they come flooding.

The play aptly showed her life: born on December 5, 1927, Lola Rosa was barely 15 years old in 1942 when she was raped twice by a Japanese officer in what is now the Fort Bonifacio. In 1943, she was captured by Japanese soldiers and was taken to a garrison in Magalang, Pampanga, where she became a sex slave for Japanese troops for nine months until she was freed by the Hukbalahap in 1944.

She and other Asian sex slaves were euphemistically called “comfort women” (jugun ianfu in Nihonggo) by their captors. Lola Rosa was the first such Filipina to tell the world about this inhuman practice of the Japanese during the war.

“There was no rest, they have sex with me every minute. That’s why we’re very tired. They would allow you to rest only when all of them had already finished. Due to my tender age, it was a painful experience for me. Sometimes in the morning and sometimes in the evening – not only 20 times,” Lola Rosa said in her book.

Lola Rosa felt some hesitation when she heard an appeal by Nelia Sancho, a member the Task Force for Filipina Military Sexual Slavery by Japan, for Filipina comfort women to stand up for their rights and demand justice as well as restitution for Japan’s war crimes against Asian women during the war. Then, on September 18, 1992, she decided to come out with her story, and to tell everyone what happened to her, with the hope that such an ordeal will never happen again to any woman.

The play has a personal link to me since I had the privilege to see and talk to Nana Rosa in person when I was a reporter then assigned to cover the Lila Filipina, the organization of former Filipina comfort women.

I last saw her during Lila’s 1996 Christmas party. Despite her failing health, one could still sense her courage, the same courage she displayed when she went public with her story: she was one of the thousands of women forced into sexual slavery by the Japanese Imperial Army during World War II.

Wearing a Filipina dress, she danced and sang with other lolas, unmindful of her deteriorating health due to a stroke she suffered after her 50-year-old daughter Rosalinda died. On August 18,1997 Lola Rosa Henson succumbed to a heart attack and died without receiving the justice she had long fought for. Her death came three days after the 52nd anniversary of the end of World War II.

I lost track of the number of Filipina comfort women who followed Lola Rosa’s example, just a minute portion of the 80,000 to 200,000 Asian comfort women who suffered systematic rape, torture, imprisonment and death at the hands of the Japanese Army during World War II.

Calling her “maestra” or great mentor, the rest of the surviving comfort women vowed to continue what Lola Rosa started.

The presence of one of the surviving comfort women, Lola Narcisa Claveria, gave more substance to last Sunday’s post-show discussions with her courage and composure in spite of the play’s deep impact on her. “Ang giyera, walang pinipili. Ayaw naming maranasan ng bagong kabataan ang dinanas naming kalupitan.”. She is living proof that the quest for justice remains alive today,

It has been more than 70 years since the war ended on August 15, 1945, and yet the Japanese government refuses to recognize its official accountability to the victims of sex slavery. Justice has not been given to women such as Rosa Henson. Their fight for unequivocal public apology, accurate historical inclusion, and just compensation continues up to this day.

The show will run up to Sunday, March 17, 2019, at the Wilfrido Ma. Guerrero Theater, 2nd floor, Palma Hall, UP Diliman, Quezon City./elb